HARALD

HARDRADA

I N MEMORY OF K NAP

HARALD

HARDRADA

T HE W ARRIORS W AY

JOHN MARSDEN

First published in 2007

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL 5 2 QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2012

All rights reserved

John Marsden, 2007, 2012

The right of John Marsden, to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 7444 1

MOBI ISBN 978 0 7524 7443 4

Original typesetting by The History Press

Contents

Authors Note and Acknowledgements

A book written in English for a non-academic readership and yet drawing on source material originally set down in Old Norse, Byzantine Greek, Russian, Anglo-Saxon and Latin does require a note as to its policy in the naming of names. As there appears to be no standard form of English spelling of early Scandinavian names, I have used whichever form seems the most appropriate in the historical context and the least intimidating for an English reader. Similarly, the title of earl is spelled in that English form where it occurs in England, but in its original Old Norse form as jarl in a Scandinavian context. Sometimes names and terms are also given in their original spelling set in italics and usually in parentheses so it might be helpful to explain that the Norse character is pronounced th (as in rather). I should also mention my specific use of the term viking in its original sense of sea-raider as distinct from the modern usage of Viking as a generic term for anyone (or anything) associated with early medieval Scandinavia.

Notes have been kept to a minimum and most often used to acknowledge references to or quotations from the work of others, but there are two such authors to whom I owe a more prominent acknowledgement because Sigfs Blndals The Varangians of Byzantium in the English edition revised and translated by Benedikt S. Benedikz was the work which played a greater part than any other in developing my interest in the man who forms the subject of this book. A more personal acknowledgement is due to my friend John Hamburg of Carrollton, Kentucky, whose unfailing enthusiasm for the same subject played its own part in encouraging this attempt at a biography of Harald Hardrada.

J.M.

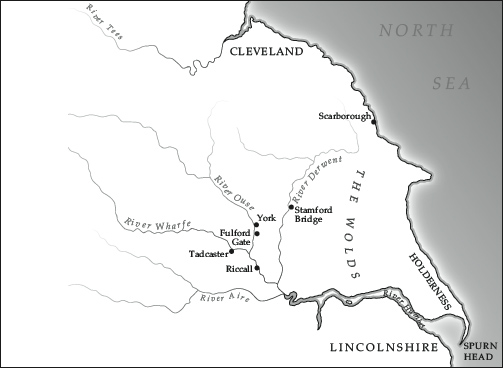

Maps

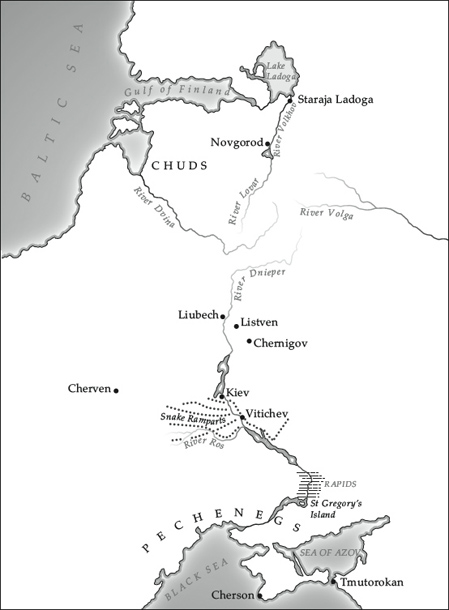

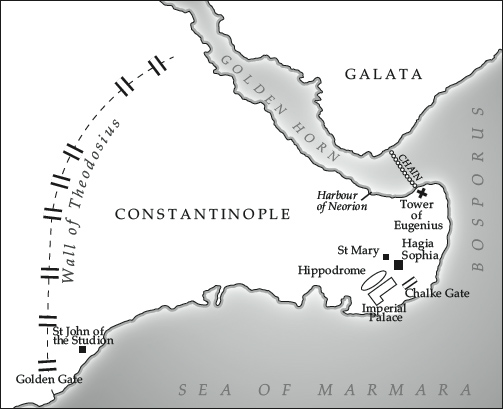

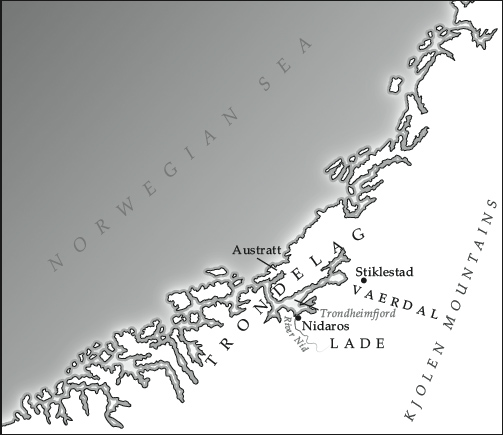

MAP 1

MAP 2

MAP 3

MAP 4

MAP 5

MAP 6

MAP 7

Sagas, Skalds and Soldiering

AN INTRODUCTION TO A MILITARY BIOGRAPHY

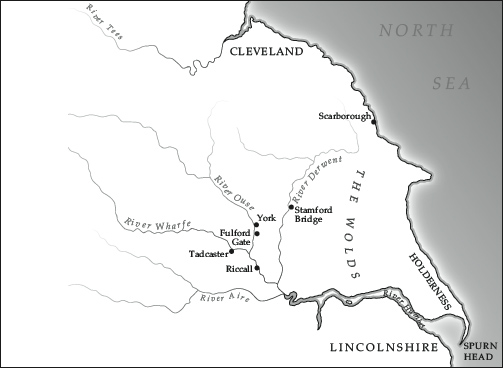

W hen he is remembered only as a Norwegian king slain in battle at Stamford Bridge in Yorkshire, where his invading army was crushed just three days before the arrival of the conquering Normans, the place of Harald Hardrada in the mainstream of English history amounts to little more than that of the third man of the undeniably memorable year 1066. He spent no more than eighteen days on English soil, after all, and the subsequent events of that fateful autumn have left him overshadowed, first by the English Harold and ultimately by William the Norman, thus obscuring his reputation acknowledged by historians ancient and modern as the most feared warrior of his world and time.

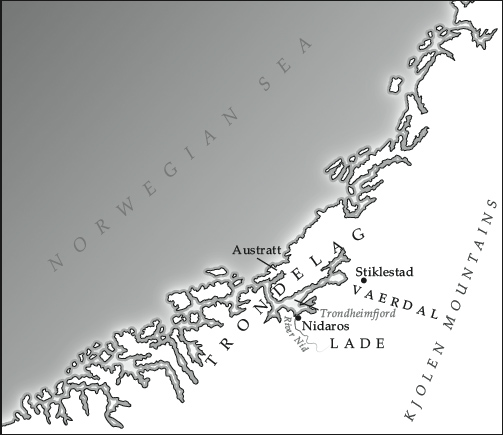

If Stamford Bridge is set into a wider context than that of Anglo-Saxon England, however, it comes into a very different focus as the last of innumerable conflicts fought out along a warriors way that had ranged across most of Scandinavia and eastward by way of Russia to the far-flung empire of Byzantium through the three and a half decades since a sturdy youngster stood with his half-brother, the king and future saint Olaf, in the blood-fray at Stiklestad in the west of Norway. The most comprehensive accounts of that great arc of warfaring are found in the thirteenth-century collections of sagas of the Norwegian kings, of which the most respected is the one known as Heimskringla and reliably attributed to the Icelander Snorri Sturluson. His version of Haralds saga is described by the editors of its standard modern English translation as a biography which in Snorris hands becomes the story of a warriors progress. Essentially it is the life and career of a professional soldier, starting with a battle the battle of Stiklestad where Harald, aged fifteen, is wounded and his brother the king killed and ending in battle, thirty-six years later, at Stamford Bridge.1

It was that observation which first suggested Harald Hardrada to me as the subject for a military biography, most especially because of its use of the term professional soldier. While there are warrior kings aplenty throughout the history of the early medieval period, and not least in the northern world, Harald can be said to stand almost, if not entirely, alone among them in having spent all the years of his young manhood on active service as a professional soldier and, quite specifically, in the modern understanding of the term.

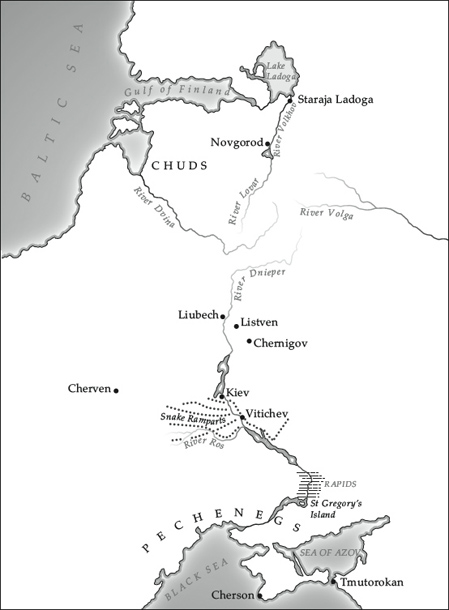

Within a year of his escape from the field of Stiklestad, he had crossed the Baltic and found his way into Russia where he reappears among the Scandinavian mercenary fighting-men employed by the Russian princes to whom they were known as Varjazi or Varangians. In that capacity and apparently as a junior officer, he is known to have taken part in a major campaign against the Poles, but assuredly also came up against the subject peoples of the northern forests and the steppe warriors to the south along the Dnieper. Some three years later he arrived in Constantinople, not yet twenty years old but already a battle-hardened commander of his own warrior company, to enter imperial service with the Varangian mercenaries of Byzantium.

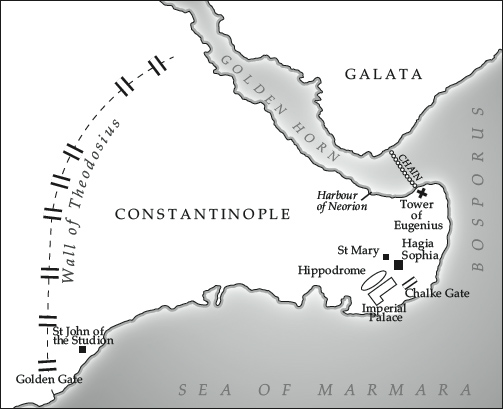

During nine years of service under three emperors, Harald saw action at sea in the Mediterranean against Saracen corsairs and on land against their shore bases in Asia Minor, led his troop on escort duty to the Holy Land and took part in the Byzantine invasion of Arab-held Sicily, before being despatched against rebellions in the south of Italy and in Bulgaria. His accomplishments in the Sicilian and Bulgarian campaigns earned him promotion to the emperors personal Varangian bodyguard in Constantinople where he was almost unavoidably although very probably not innocently caught up in the whirlpool of Byzantine politics. Subsequently falling from imperial favour, he was briefly imprisoned before escaping in time to play his own grisly part in the downfall of an emperor amid the bloodiest day of rioting ever seen in the city. Shortly afterwards Haralds ambitions turned back towards his homeland and, despite having been refused imperial permission of leave, he launched his ships in a daring departure from Constantinople to begin the long journey north.