For Harald

May I be his last and greatest skald

Contents

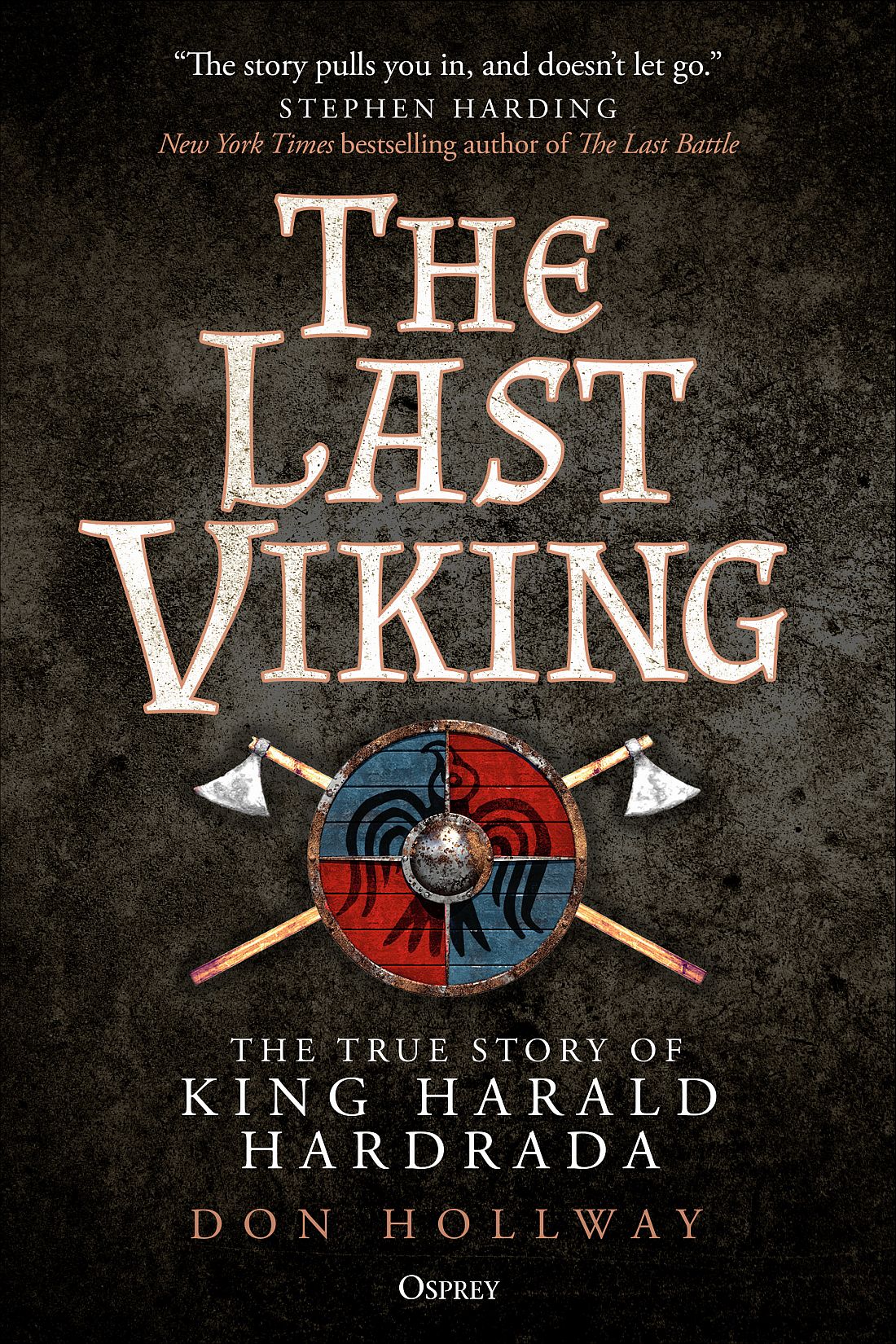

The Last Viking is dedicated to King Harald III Sigurdsson, called Hardrada. As his biographer, in making sure hes never forgotten, I would be remiss if I forgot to acknowledge the many people who have helped me tell his story.

Fellow re-enactor Carl Gnam, publisher of Military Heritage magazine, and Ed Zapletal, publisher of History Magazine , are friends who have done much more for me than furnish favorable reviews. Special thanks to my editors at HistoryNet.com: Carl von Wodtke at Aviation History magazine, who, when after a twenty-year hiatus I took up writing again (on a computer instead of typewriter), remembered me from the old days and set the standard by which all other editors are compared; and Stephen Harding at Military History magazine, who not only published my work but thought enough of it to introduce me to his our agent.

The folks at Osprey Publishing, part of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, have been more than patient with a magazine writer venturing into a book-publishing world: in New York, Rayshma Arjune, Publicity Manager, Special Interest, Bloomsbury USA; in England, Emily Neat ( ne Heagerty!), Osprey Head of Marketing; Gemma Gardner, Osprey Senior Desk Editor, who polished my Old Norse; and above all, Kate Moore, Osprey Commissioning Editor, who saw something in The Last Viking actually, in just the first few chapters that lesser editors did not. Im sure I drove you all a little bit crazy; as I write this, I probably still am. Thanks for indulging me, and thanks so much for making The Last Viking worthy of Osprey. For most of my life Osprey books have been my go-to source on any history topic. I have bookshelves full of them to prove it. I can tell friends in my history-buff re-enacting circles that Im published and get a big Meh. Telling them Im published by Osprey, though, gets me instant street cred. (They all have bookshelves full, too.) I am honored to be in the stable.

And, of course, thanks most of all to my agent, Scott Mendel, Managing Partner of Mendel Media Group LLC, who changed my life by reaching out to ask, What do you know about Vikings?

The rest, as they say, is history.

In the high latitudes of the far north it feels as though the summer sun will never set, but when night falls it seems to last forever. By the mid-13th century, the day of the Vikings had long since gone dark. In Ireland, in 1171, the Norman-Irish themselves partly the descendants of Vikings captured Dublin, forcing its Norse-Irish king into exile. In 1263 the Scots under Alexander III repelled the attempt by Norways King Hakon Hakonarson to reclaim rule over Scotland. By 1240 a new scourge of Christendom, the Mongols, had conquered the heirs of the Viking prince Rurik in the land of the Rus, and everywhere else the adherents of Christ had converted the sons of Odin to the new, supposedly gentler faith. The colony in Vinland Newfoundland had been abandoned, and those in Greenland were slowly withering. The entire North was growing colder, as the world slid from the benevolence of what we now call the Medieval Warm Period ( c . 950 c . 1250) into the Little Ice Age. And this was all long after the fact; historians generally date the end of the Viking Age to an early autumn day in England in the year 1066.

Almost 200 years later and 500 miles away, at Reykholt in the far west of Iceland, it fell to one man to set down the history of Norwegian kings. There are no surviving portraits of Snorri Sturluson from life, but during his lifetime in the mid-13th century he was already famous across the North as the author of the Prose Edda , an account of Norse mythology. Scholar, writer, poet and historian, the Homer of the North, Snorri was a Renaissance man well before the Renaissance. Lacking the traditional Viking skill in combat he seems rarely if ever to have been involved in a fight, and may even have been something of a coward Snorri instead parlayed his skill with words into a political career. At age fifty he was the richest and most powerful chieftain in Iceland, a colony of ex-Norwegian outlaws and exiles. Twice elected as lawspeaker to the national parliament, the Althing , he was, for all practical purposes, an uncrowned king. Yet he had agreed to become a jarl (earl), a vassal of Norways King Hakon IV, and to represent him to Icelands bickering chiefs or to play the ruler against them, which had turned out to please no one. Now, as both Norway and Iceland spiraled down into separate civil wars, Snorri seemed to recognize that for the feuding chiefs to rise above themselves would require deeds worthy of the sagas. He himself was not up to such tasks, but perhaps it would be enough to simply remind the Icelanders the Norse of the great deeds of their forebears, going back to the days of legend when mighty Odin led the ancient Aesir out of Asgard to become the first Scandinavians.

In the stony, moss-covered valley of the Reykjadalsa River, riven with geothermal vents and geysers, each known for centuries by its own name, Snorri moved into a farmstead near the hot spring called Skrifla. He fed its water via conduit into a circular, stone-lined outdoor bath that he named Snorralaug (literally Snorris Pool), connected to his house by an underground tunnel. The Sturlunga Saga , written after his death about Snorris powerful clan, the Sturlungs, includes a passage wherein Snorri and his friends relax together in this pool with drinks in hand, perhaps reciting the age-old sagas under the northern lights, or by moonlight scattered on silvery steam-clouds wafting across the valley from the nearby geysers.

Snorralaug and Snorris connecting passage still exist today (if a bit overwhelmed by the big modern hotel, museum and gift shop clustered around them), thought possibly to be the oldest extant structures in Iceland. Archaeological excavations of the old farmstead have uncovered shards of French-style stemmed glasses; clearly Snorri lived life to the fullest. (In addition to being a renowned drinker, he was a notorious philanderer who fathered at least seven children by four different women.) One can sit on the flagstone patio and run a hand through the warm waters of the pool and imagine Snorri late at night, rising naked and dripping from these same waters and perhaps enjoying a quick, very Scandinavian roll in the snow. Then he totters, drink in hand, into the tunnel and up a spiral staircase into the writing studio of his Norwegian-style loft house, there to contemplate the collected tales that were to comprise his greatest work.

Snorri had several primary sources he could pull down off his bookshelf. Heavy, leather-bound manuscripts, laboriously copied by hand, they were valuable beyond words, though in the wild old days an illiterate Viking looter would have considered them useful only as tinder and kindling. Snorris personal editions are long lost, but copies survived. Two were named in later times for the condition of the vellum on which the originals were written: the Morkinskinna ( Moldy Parchment ) and Fagrskinna ( Fair Parchment ). Though each was inscribed around the year 1220, they are compilations of even earlier, lost accounts of the lives and deeds of Norwegian kings. The Fagrskinna reached over 400 years into the past in Scandinavia, practically prehistory, so far back that many of the kings named are now considered partly or even mostly mythological. These sagas were recited orally, handed down by memory across generations and naturally subject to induced errors and then passed along until finally written down as if original and factual.

![Haywood - Viking: The Norse Warrior’s [Unofficial] Manual](/uploads/posts/book/98981/thumbs/haywood-viking-the-norse-warrior-s.jpg)