Hattie McDaniel:

Black Ambition, White Hollywood

Mae West:

An Icon in Black and White

God, Harlem U.S.A.:

The Father Divine Story

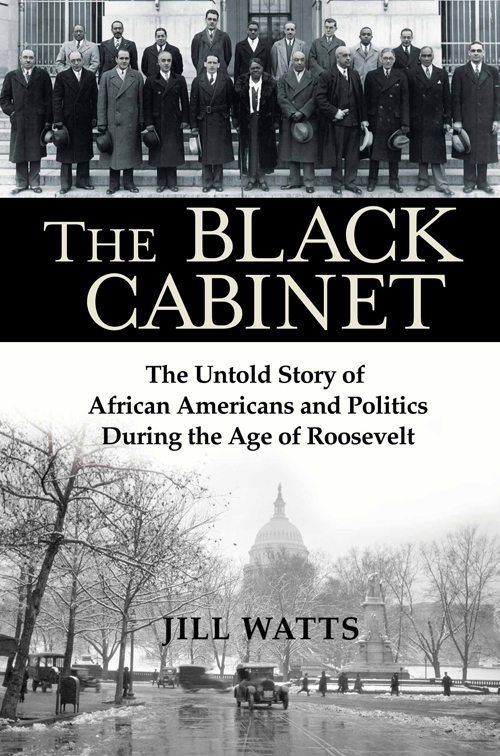

T HE BLACK CABINET

The Untold Story of African Americans and Politics During the Age of Roosevelt

JILL WATTS

Copyright 2020 by Jill Watts

Cover design by Gretchen Mergenthaler

Cover photographs: Roosevelts black advisors in 1938 Scurlock

Studio Records, Archives Center, National Museum of American

History, Smithsonian Institution; Washington DC alamy

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Scanning, uploading, and electronic distribution of this book or the facilitation of such without the permission of the publisher is prohibited. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the authors rights is appreciated. Any member of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use, or anthology, should send inquiries to Grove Atlantic, 154 West 14th Street, New York, NY 10011 or permissions@groveatlantic.com.

FIRST EDITION

Published simultaneously in Canada

Printed in the United States of America

First Grove Atlantic hardcover edition: May 2020

This book was designed by Norman Tuttle of Alpha Design & Composition.

This book set in 13-point Centaur MT by Alpha Design & Composition of Pirttsfield, NH.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data is available for this title.

ISBN 978-0-8021-2910-9

eISBN 978-0-8021-4692-2

Grove Press

an imprint of Grove Atlantic

154 West 14th Street

New York, NY 10011

Distributed by Publishers Group West

groveatlantic.com

20 21 22 23 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For my mom

Doris Ruth Watts

For my nieces

Sarah and Abby Woo

George Armstrong

Frazier Baker and his one-year-old daughter, Julia

Anne Bostwick

John Lee Eberhart

Thomas P. Foster

Gus

Felix Hall

Robert Hall

Paul Mayo

Claude Neal

William Norman

Odell Waller

And other victims of lynching and racial violence who have lost their lives

Some of the language in this book was and is offensive. It is quoted here from the original sources to offer insight into historical realities that African Americans of the era faced and to illuminate the struggles of Black Cabinet members in their fight for equality.

I N THE middle of January 1940, Mary McLeod Bethune awoke early in her Washington, D.C., home. A dry wheezing, punctuated by a breathless cough, often stirred her, and she would rise, sometimes well before dawn. She grabbed the doctors latest remedy, then made her way to the kitchen for a hot cup of tea. For much of her life, she had suffered asthma attacks, and this winter they seemed worse. And now, at sixty-four, she was also plagued by arthritis and had to use a cane to get about. Yet, she refused to be stilled and seemed to possess a reserve of boundless energy. Her life had been filled with hard work, and no matter what obstacle she faced, she would notcould notrest.

Born in Mayesville, South Carolina, in 1875, Mary McLeod Bethune was the daughter of parents who had both endured slavery. Freed after the Civil War, her family sharecropped for a time, and as a youth, Bethune had worked alongside her mother, father, and siblings in cotton fields and cold, swampy rice paddies. But she hungered for a better life; she fought for an education, received a scholarship, and left home. During summer breaks, to help pay for her schooling, Bethune took jobs as a cook and a maid in white homes. Drive and industry and, she insisted, womens club movement, and a celebrated civil rights activist. In 1936, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt personally offered her a position in the New Deal, his administrations massive collection of federal agencies and programs aimed at healing Americas Great Depression, the most serious economic crisis in the nations history. Mary McLeod Bethune accepted an appointment to head up a work program for African American youth, and with that, she became the first African American woman to lead a federal division.

Almost immediately after settling into her new post, Bethune took command of an informal group of black federal employees known as .

What she had achieved was not lost on her. it is to yearn for a chance to do something, to be something better, she remarked in one interview. When I was very young I resolved to lift myself, somehow, out of the confusion and misery of those [post-Civil War] days, and in lifting myself I found a higher motive, that of lifting others. By winter 1940, she had been battling for African American equality in the federal government for almost six years, and she continued to drive hard. Much was at stake. The Great Depression had gripped the nation for more than a decade. Although the economy had begun to turn around, homelessness and poverty persisted in parts of the nation. Hitler and Nazism had moved throughout Europe, and on the other side of the world, tensions had grown with Japan.

While these threats loomed large over the nation, much of the African American community remained destitute. In 1933, when Franklin Delano Roosevelt first took office, unemployment in many African American communities ran at 50 percent or higher, twice the national average. Of the nearly twelve million African Americans living in the United States counted in the 1930 census (who composed almost 10 percent of the entire population), 73 percent lived in the rural South and faced dire poverty and the threat of starvation. The vast majority of black southerners were denied the right to vote. Overall the outlook for African American citizens during the Great Depression was grave. Segregated in communities across the country, subjected to racial violence, and denied equal access to education, social and legal justice, health care, and jobs, many African Americans, rather than recovering by 1940, continued to fall desperately further and further behind. Black people and their sufferings were never far from Bethunes mind. She believed that she had been brought into the world with a special purposeand that was to end the brutalities against the African American people and lead them to equality. Deeply devout, she began every morning in prayer. These cold January winter mornings were no different.

By the second week of the month, rain had turned to snow and then to rain again. Bethunes doctors had cautioned her to slow down, but she refused. New anti-lynching legislation known as the Gavagan bill, named for its sponsor, New York congressman Joseph A. Gavagan, was making its way through the House of Representatives. Bethune steeled herself for the fight to get it passed. Since emancipation and the end of the Civil War in 1865, lynching as a means to terrorize the black population had become a public ritual, especially below the Mason-Dixon Line that historically designated the geographic division between North and South. Unchecked by local and state authorities, white mobs took the law into their own hands and tortured, mutilated, and killed black men, women, and children. Lynch mobs were brazen. White crowds posed for photographsarrogantly grinning and laughing as black bodies were hung from trees, were riddled to shreds by bullets, were stabbed, and were set on fire.