ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Blake Edgar, acquisitions editor for the University of California Press, has my thanks for askingjust as my previous volume with the University of California Press (Folsom, 2006) was rolling off the presseswhether I had another book in the offing. Here tis.

Blake, as well as Wendy Ashmore, Tom Dillehay, Donald Grayson, Torrey Rick, and David Hurst Thomas read the entire manuscript, and provided detailed and helpful comments. Daniel Mann and Stephen Zegura, geologist and geneticist, respectively, provided constructive, detailed critiques of chapters 2 (Mann), and 5 and 6 (Zegura), thereby saving me possible embarrassment in venturing into disciplines not my own. I am extremely grateful for the help of all, and hereby absolve them of blame for any lingering errors.

As with all my work, I've been able to rely on friends and colleagues who've kindly answered questions (or asked pointed ones), given advice, supplied references or unpublished manuscripts, or otherwise rendered aid along the way. For that I'd like to thank Michael Adler, Tony Baker, Douglas Bamforth, Lewis Binford, Deborah Bolnick, Michael Cannon, Tom Dillehay, Arthur Dyke, Sunday Eiselt, Michael Gramly, Donald Grayson, Michael Hammer, Vance Holliday, Karl Hutchings, Brian Kemp, Jeffrey Long, Dan Mann, Daniel Moermann, Connie Mulligan, James O'Connell, Nick Patterson, Torrey Rick, Theodore Schurr, Vin Steponaitis, Noreen Tuross, Richard Waitt, Cathy Whitlock, and Don Yeager.

For providing photographs or help with other illustrations, I am grateful to Jim Adovasio, Tony Baker, Alex Barker, Charlotte Beck, Michael Collins, Deborah Confer, Judith Cooper, Joseph Dent, Tom Dillehay, Boyce Driskell, Steve Emslie, Michael Gramly, Eugene Hattori, Louis Jacobs, George Jones, David Kilby, Jason LaBelle, Anne Meltzer, Ethan Meltzer, Jeff Rasic, Richard Reanier, Torrey Rick, Richard Rose, Mark Stiger, Lawrence Straus, Renee Walker, Fred Wendorf, David Willers, David Wilson, Michael Wilson, Tom Wolff, and David Yesner. I am particularly indebted to Katherine Monigal, who put her considerable artistic and computer talents to work on many of the figures in the book, and thereby saved me from having to get over my loathing of Adobe Photoshop (Adobe Illustrator and I still remain on quite good terms).

Several years ago I was fortunate to participate in a series of fascinating National Science Foundation-sponsored conferences organized by John Moore and Bill Durham that brought together archaeologists, geneticists, linguists, and social anthropologists to explore issues related to the colonization of new landscapesand not just the Americas, but also Australia and the islands of Oceania. These sessions and my fellow participants contributed immeasurably to my thinking about these matters.

This book was written in the spring of 2007 while I was on a Research Fellowship Leave from Southern Methodist University, for which I am most grateful. My archaeological fieldwork and historical research touched on here have been supported by grants from the National Science Foundation, the Potts and Sibley Foundation, and especially (over the last decade) by the Quest Archaeological Research Fund, generously established at SMU by Joseph and Ruth Cramer.

In the fall of 1992, when I was writing Search for the First Americans, my children were four and six years old. And so I wrote at my university office to avoid the wonderful and welcome distractions of home. The children have since flown the nest for their own universities far away. And so I wrote First Peoples in my son's roomnow converted to an office. But I miss those wonderful distractions that used to be home. Shadow the dog tried his best to fill the void, but it was just not the same.

David J. Meltzer

Dallas, Texas, January 2008

OVERTURE

It was the final act in the prehistoric settlement of the earth. As we envision it, sometime before 12,500 years ago, a band of hardy Stone Age hunter-gatherers headed east across the vast steppe of northern Asia and Siberia, into the region of what is now the Bering Sea but was then grassy plain. Without realizing they were leaving one hemisphere for another, they slipped across the unmarked border separating the Old World from the New. From there they moved south, skirting past vast glaciers, and one day found themselves in a warmer, greener, and infinitely trackless land no human had ever seen before. It was a world rich in plants and animals that became ever more exotic as they moved south. It was a world where great beasts lumbered past on their way to extinction, where climates were frigidly cold and extraordinarily mild. In this New World, massive ice sheets extended to the far horizons, the Bering Sea was dry land, the Great Lakes had not yet been born, and the ancestral Great Salt Lake was about to die.

They made prehistory, those latter-day Asians who, by jumping continents, became the first Americans. Theirs was a colonization the likes and scale of which was virtually unique in the lifetime of our species, and one that would never be repeated. But they were surely unaware of what they had achieved, at least initially: Alaska looked little different from their Siberian homeland, and there were hardly any barriers separating the two. Even so, that relatively unassuming event, the move eastward from Siberia into Alaska and the turn south that followed, was one of the colonizing triumphs of modern humans, and became one of the great questions and enduring controversies of American archaeology. Those first Americans could little imagine our intense interest in their accomplishment thousands of years later, and would almost certainly be puzzledif not bemusedat how seemingly inconsequential details of their coming sparked a wide-ranging, bitter, and long-playing controversy, ranking among the greatest in anthropology and entangling many other sciences.

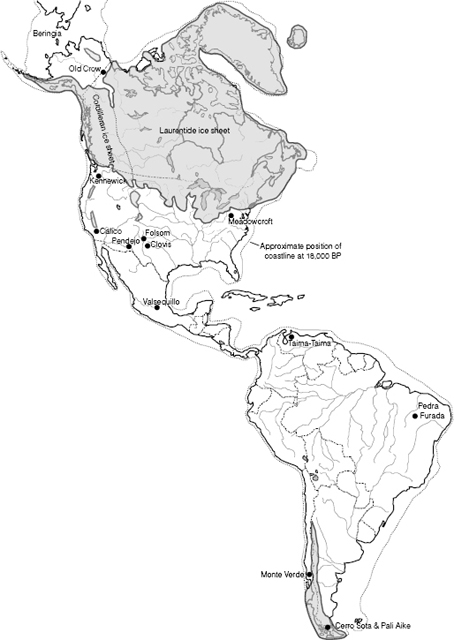

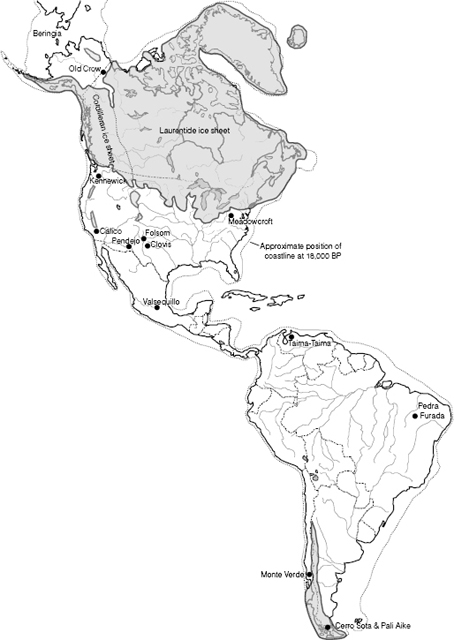

FIGURE 1.

Map of the Western Hemisphere, showing the extent of glacial ice at the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) 18,000 years ago, the approximate position of the coastline at the time, and some of the key early sites, archaeological and otherwise, hemisphere-wide.

Here are the bare and (mostly) noncontroversial facts of the case. The first Americans came during the Pleistocene or Ice Age, a time when the earth appeared vastly different than it does today. Tilts and wobbles in the earth's spin, axis, and orbit had altered the amount of incoming solar radiation, cooling Northern Hemisphere climates and triggering cycles of worldwide glacial growth. Two immense ice sheets up to three kilometers high, the Laurentide and Cordilleran, expanded to blanket Canada and reach into the northern United States (while smaller glaciers capped the high mountains of western North America).

As the vast ice sheets rose, global sea levels fell approximately 120 meters, since much of the rain and snow that came down over the land froze into glacial ice and failed to return to the oceans. Rivers cut deep to meet seas that were then hundreds of kilometers beyond modern shorelines (). Lower ocean levels exposed shallow continental shelf, including that beneath the Bering Sea, thereby forming a land bridgeBeringiathat connected Asia and America (which are today separated by at least ninety kilometers of cold and rough Arctic waters). When Beringia existed, it was possible to walk from Siberia to Alaska. Of course, once people made it to Alaska, those same glaciers presented a formidable barrier to movement further southdepending, that is, on precisely when they arrived in this far corner of the continent.

These ice sheets changed North America's topography, climate, and environment in still more profound ways. It was colder, of course, during the Ice Age, but paradoxically winters across much of the land were warmer. And the jet stream, displaced southward by the continental ice sheets, brought rainfall and freshwater lakes to what is now western desert and plains, while today's Great Lakes were then mere soft spots in bedrock beneath millions of tons of glacial ice grinding slowly overhead.

Next page