Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

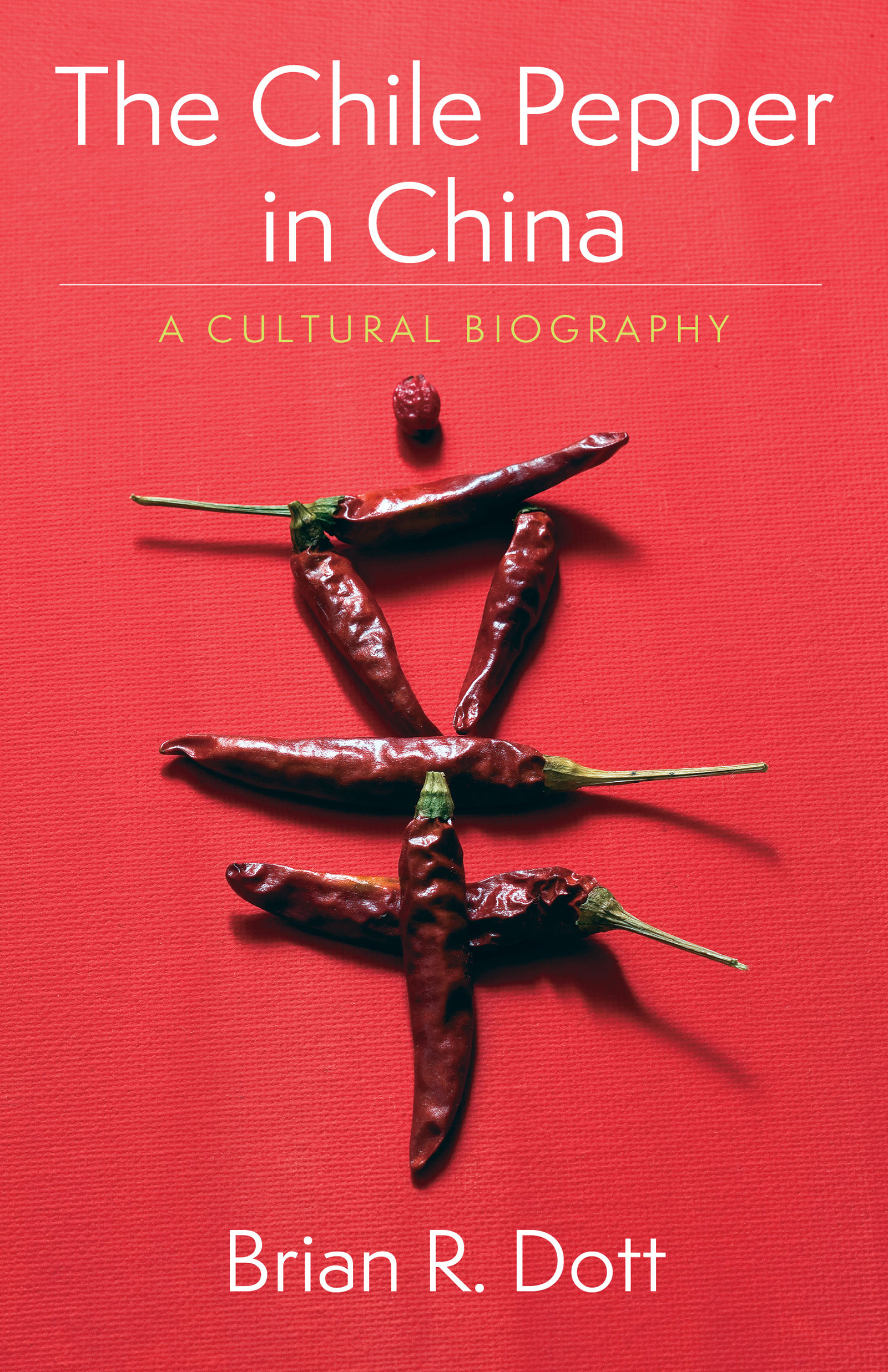

The Chile Pepper in China

ARTS AND TRADITIONS OF THE TABLE PERSPECTIVES ON CULINARY HISTORY

ARTS AND TRADITIONS OF THE TABLE PERSPECTIVES ON CULINARY HISTORY

Albert Sonnenfeld, Series Editor

For a complete list of titles, see .

THE CHILE PEPPER IN CHINA

A Cultural Biography

BRIAN R. DOTT

Columbia University Press

New York

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

Copyright 2020 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-55130-4

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Dott, Brian Russell, author.

Title: The chile pepper in China : a cultural biography / Brian R. Dott.

Description: New York : Columbia University Press, [2020] | Series: Arts and traditions of the table : perspectives on culinary history | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019038653 (print) | LCCN 2019038654 (ebook) | ISBN 9780231195324 (cloth)

Subjects: LCSH: Hot peppersChinaHistory. | Cooking (Hot peppers)ChinaHistory. | Cooking, ChineseHistory. | Food habitsChinaHistory.

Classification: LCC SB307.P4 D68 2020 (print) | LCC SB307.P4 (ebook) | DDC 633.8/40951dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019038653

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019038654

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

Cover design: Milenda Nan Ok Lee

Cover image: Hitoshi Kamizumi/a.collectionRF/ Getty Images

In memory of my parents,

who taught me to be curious about the natural world.

Nancy Robertson Dott

naturalist

(19292018)

Robert H. Dott, Jr.

geologist

(19292018)

CONTENTS

Names and Places: How the Chile Found Its Way Home to China

Spicing Up the Palate

Spicing Up the Pharmacopeia

Too Hot for Words: Elite Reticence Toward Chile Peppers

Chiles as Beautiful Objects and Literary Emblems

Maos Little Red Spice: Chiles and Regional Identity

Many people have provided me with support and assistance throughout this book project. Sarah Scheewind, Yi-Li Wu, and Evelyn Rawski all gave me valuable advice and feedback on my first stab at writing a narrative for the history of the chile. Members of the History Department at Whitman College provided feedback at various stages of the project. Audiences at presentations at the Qing History Institute at Renmin University in Beijing and at the Needham Institute in Cambridge asked probing questions that pushed me further in my understanding and analysis. Shu-chu Wei-Peng, Qiulei Hu, and Donghui He all helped me decipher cryptic passages in classical Chinese. Wencui Zhao gave me assistance with nuances of modern Chinese and helped me navigate obtaining permissions in China. Dong Jianzhong, at the Qing History Institute at Renmin University, hosted me on several occasions in Beijing, aiding in numerous ways, both scholarly and personally. Xu Wangsheng at the China Agriculture Museum in Beijing assisted by tracking down important scholarly works on chiles in Chinese. Wang Maohua brought the illustrated text by Huang Fengchi to my attention. Annelise Heinz provided research assistance at the beginning stages of the project.

Chef Wang Taohong in Beijing demonstrated a variety of cooking methods, engaged me in a stimulating culinary conversation, and taught me to look for chiles in the cuisines of traditionally nonspicy regions. Traditional Chinese Medicine practitioner Alex Tan clarified a number of medical concepts. Li Yongxian from Sichuan University expanded my understanding of the place and role of chiles in Sichuan culture. He took the time to tour me around Pixian, where I deepened my appreciation of douban jiang. Librarians at Harvard-Yenching, the University of Washington, Beijing Universitys rare book collection, and the National Library of China all provided invaluable assistance tracking down materials. At Whitman College, Jen Pope did an extraordinary job obtaining numerous books through interlibrary loan. Jennifer Crewe, at Columbia University Press, helped me turn a manuscript with potential into a much more readable book.

Whitman College and the History Department both provided travel expenses for multiple research trips to China, as well as the University of Washington Library and the Harvard-Yenching Library. Sally Bormann has aided me in this project in many ways, as an amazing editor, providing feedback, and especially as someone who pushed me to think deeper and write better.

All translations in the book are my own unless noted otherwise.

Shennong, inventor of agriculture and medicine | (legendary ruler) |

Shang dynasty | c. 17661045 BCE (before Common Era, equivalent to BC ) |

Zhou dynasty | c. 1045256 BCE |

Qin dynasty | 221207 BCE |

Han dynasty | 207 BCE 220 CE (Common Era, equivalent to AD ) |

Period of disunity | 221589 |

Sui dynasty | 589618 |

Tang dynasty | 618907 |

Five Dynasties period | 907960 |

Song dynasty | 9601279 |

Yuan dynasty (Mongols) | 12791368 |

Ming dynasty (Han Chinese) | 13681644 |

Qing dynasty (Manchus) | 16441911 |

Republic of China | 19111949 (to present on Taiwan) |

Peoples Republic of China | 1949present (mainland China) |

Red chile,

Pointed chile,

Spicy chile,

So tasty!

Chinese folk rhyme

Chinese cuisine without chile peppers? Unimaginable! Yet, there were no chiles anywhere in China prior to the 1570s. All varieties of chile pepper, from sweet to extremely spicy, from long and pointed to round, belong to species native to Central America and northern South America and therefore had to be introduced to China. This book was sparked by an epiphany when I was enjoying a spicy meal at a Sichuanese restaurant in Beijing and asked myself, How did the Chinese begin to eat something new with such an intense flavor as chile peppers? I started seeing chiles everywherereal dried ones hanging from the eaves of traditional homes, decorative glass ones hanging from rear-view mirrors keeping images of Chairman Mao company, in contemporary music videos, and in an eighteenth-century novel. Today chiles are so common in China that many Chinese assume they are native. Indeed, in the mid-twentieth century Mao Zedong even asserted that revolution would be impossible without chiles!

In the twenty-first century I presented on some preliminary findings to an audience of Chinese historians in Beijing, and many of them were astounded that chiles are not indigenous. Surely, several asked, some of the varieties we enjoy are native!? While the Chinese have certainly bred varieties to suit their tastes and needs over the past few hundred years, initial introduction came from abroad. In this book I trace the intricacies and complexities of answers to two deceptively simple questions: How did chile peppers in China evolve from an obscure foreign plant to a ubiquitous and even authentic spice, vegetable, medicine, and symbol? And how did Chinese uses of chiles change Chinese culture?