Fall River Press and the distinctive Fall River Press logo

are registered trademarks of Barnes & Noble, Inc.

1997 by Peter Morton Coan

Cover art courtesy of Corbis Images, New York

Cover design by Tom McKeveny

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher.

ISBN 978-1-4114-6865-8 (e-book)

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

For information about custom editions, special sales, and premium and corporate purchases, please contact Sterling Special Sales at 800-805-5489 or specialsales@sterlingpublishing.com

www.sterlingpublishing.com

F or my daughters Melissa and Sara,

and for all the courageous souls

who passed through the Golden Door.

On the boats and on the planes

Theyre coming to America

Never looking back again

Theyre coming toAmerica

Home, dont it seem so far away

Oh, were traveling light today

In the eye of the storm

In the eye of the storm

Home to a new and a shiny place

Make our bed, and well say our grace

Freedoms light burning warm

Freedoms light burning warm...

NEIL DIAMOND, FROM THE SONG AMERICA

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to the National Park Service, which operates the Statue of Liberty/Ellis Island Monument, and to those who so capably help to keep its memory alive: Diana Pardue, chief curator; Dr. Janet Levine, oral historian; Paul Sigrist, chief oral historian; and Kevin Daley, photographer.

Special thanks go to Peter Hom of the Ellis Island Oral History Project for helping me find and select immigrant interviews for possible inclusion in this book. His advice, research assistance, and overall cooperation were invaluable. I am particularly grateful to Barry Moreno who, along with Jeff Dosik, heads the Ellis Island Research Library. Morenos extraordinary knowledge of the history of immigration and Ellis Island are apparent in the Foreword. I also want to thank Dr. John Parascandola, historian at the U.S. Public Health Service in Rockville, Maryland, for his statistical help.

Finally, this book would not have been possible without the fine and determined efforts of my agent, Carol Mann, and my editor, Hilary Poole, who did a masterful job, and editorial director Laurie Likoff, whose belief and support have been unwavering. The other key unsung heroes at Facts On File, and I thank them all, are: Lisa Milberg, director of marketing; Kate Moore, publicity manager; Paul Conklin, director of sales; Sarah Muir, trade sales manager; and Antonio Gomez, director of electronic media. I would also like to thank Facts On File chairman Mark McDonnell for his vision and commitment to the project.

P. M. C.

Foreword

T hough the recorded history of Ellis Island goes far back to early colonial times, the small island only emerged out of local obscurity onto the stage of American history in 1892, when it became the headquarters of the federal Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) for the New York areaa location that dominated the scene of worldwide immigration to Americas shores. Like the slender thread of Irish folklore that holds up the key elements of social existence, so Ellis Island, as small as it was, became Americas slender thread for the peopling of the nation. The federal government endowed Ellis Island with a significance that changed lives.

The overall immigration statistics for the island are impressive. More than 12 million immigrants, or aliens, as they were called, underwent immigration processing or detention at Ellis Island from January 1, 1892 until November 12, 1954a span of sixty-two years. During those years, the island was the scene of more human dramas than one can imagine. They involved not just foreigners trying to enter the United States but foreigners already living here, who found themselves on Ellis Island for special inquiry and possible deportation as enemy aliens during the First and Second World Wars. The INS regularly issued warrants for their arrest and deportation.

But Ellis Islands heyday, 18921924, covered the years when the immigration laws of the United States were comparatively liberal. The federal government created the INS, originally called the Bureau of Immigration, and opened Ellis Island and other immigrant stations at seaports throughout the United States as landing depots to weed out undesirable immigrants. Those depots on the East Coast included Baltimore, Philadelphia, Providence, and Boston, and on the West Coast, Angel Island in San Francisco Bay (whose principal function was to exclude Chinese aliens).

The federal law was straightforward. The INS was required to enforce the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, the Contract Labor Law of 1885, and the Immigration Act of 1891. The latter piece of legislation excluded all mentally disabled persons, paupers, and those who might become public charges. It excluded those suffering from a loathsome or contagious disease, as well as those convicted of a felony, an egregious crime, or a misdemeanor involving moral turpitude. Anarchists were added to the list of unacceptable aliens in 1903. Illiterates faced exclusion beginning in 1917.

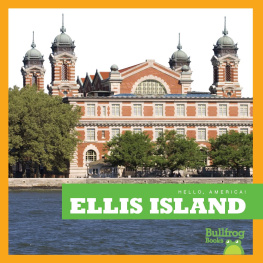

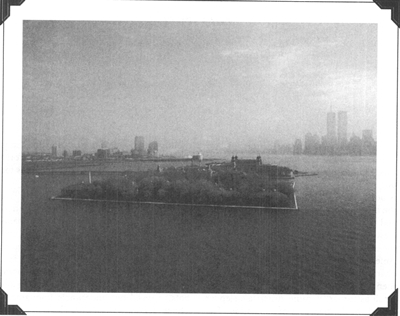

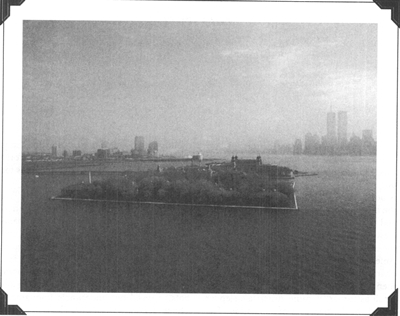

Late 1980s photograph of Ellis Island on a misty day. In the foreground are the still abandoned buildings of the contagious disease wards on what was known as Island Three, where Dr. James Baker performed his medical experiments and electroshock therapy on immigrants and U.S. naval personnel from 1949 to 1951. Island Two contained the general hospital wards and lunatic asylum. Only the main building containing the Registry Room on Island One was renovated from 198490.

(NATIONAL PARK SERVICE: STATUE OF LIBERTY NATIONAL MONUMENT)

The processing of aliens began as steamships entered New York Harbor. Boarding division inspectors and physicians from Ellis Island met the ships by cutter and examined first- and second-class passengers aboard the vessels. A few of these people were occasionally detained for further processing at Ellis Island, but the majority were released and were saved a visit to Ellis Island because they satisfied immigration officials of their comparative wealth, social standing, good health, or that they were simply temporary visitors.

By far, the greater number of passengers traveled in steerage or third class. These passengers were all required to go to Ellis Island for more extensive processing. Experience taught the INS that steerage passengers intended to remain in the United States but, often, were poor, illiterate, and in ill health.

Next page