ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

For many years, I have been fortunate in working with a fine group of colleagues at the Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island. I am grateful for their unfailing encouragement and kindness in all of my endeavors at the monument and museum. In particular, I would like to thank Jeffrey S. Dosik, Diana Pardue, Eric Byron, Janet Levine, Kevin Daley, Cynthia Garrett, George Tselos, Sydney Onikul, Frank Mills, Ken Glasgow, Richard D. Holmes, Don Fiorino, Judith Giuriceo, Paul Roper, Geraldine Santoro, Nora Mulrooney, Doug Tarr, Michael Conklin, Steve Thornton, Brian Feeney, Peter Stolz, Peg Zitko, Sgt. Charles Guddemi of the park police, David Diakow, Katharine Daley, and my friends who work on the Statue of Liberty-Ellis Island ferry boats, especially Luciano Terkovich.

I would also like to thank our parks volunteers, especially Charles Chick Lemonick, David Cassells, Marcus Smith, John Kiyusu, Mary Fleming, North and Jesse Peterson, Javier Agramonte, and the late Richard Kwiatkowski. The research and friendship of historians Marian L. Smith of the U.S. Bureau of Citizenship and Immigration Services, Peter Mesenhoeller of Germany (who has generously shared his research on Augustus Sherman), Brian G. Andersson of the New York City Municipal Archives, Robert Stein of the City University of New York, and Robert Morris and John Celardo of the National Archives, have also been invaluable. In addition, I appreciate the help and encouragement of my friends Loretto D. Szucs, Philip Wilner, Lorie Conway, Joseph Michalak, Kevin Sherlock, Louise Muse, Rosemary Gelshenen, John Devanny, Isabel Belarsky, Tom Bernardin, Brian Ockram, and the late vaudeville and radio star Arthur Tracy, known as the Street Singer. Because I have long admired the books made by Arcadia Publishing, I must thank editors Susan E. Jaggard and Pamela ONeil, as well as graphic designer Brendan Cornwell, for letting me work on this book with them.

The pictures in this volume are largely drawn from the collections of the National Park Service, the Library of Congress, the National Archives, and the U.S. Bureau of Immigration. Those from other collections are as follows: Ellis Island Dining Room (p. 110), New York Public Library; Rev. Fr. Gaspare Moretto (p. 63), Dr. Emelise Aleandris Little Italy; Cipriano Castro (p. 79), Corbis/Bettman; and Mulberry Street (p. 88), Museum of the City of New York. From the authors collection came the Paris (p. 28); Ellis Island, (p. 94); The Street Singers Radio Song Book, (p. 100); Oland (p. 101); Newman (p. 102); Weissmuller (p. 104); Von Stroheim and Cugat (p. 105); Auer (p. 106); Colman (p. 107); Cortez (p. 108); Trenet (p. 110); a World War II brochure and view of the Statue of Liberty (p. 119); the author on the roof (p. 120); the autopsy room and Ellis reopening brochure (p. 121); and Silent Voices (p. 124).

Find more books like this at

www.imagesofamerica.com

Search for your hometown history, your old

stomping grounds, and even your favorite sports team.

One

FROM CASTLE GARDEN TO ELLIS ISLAND

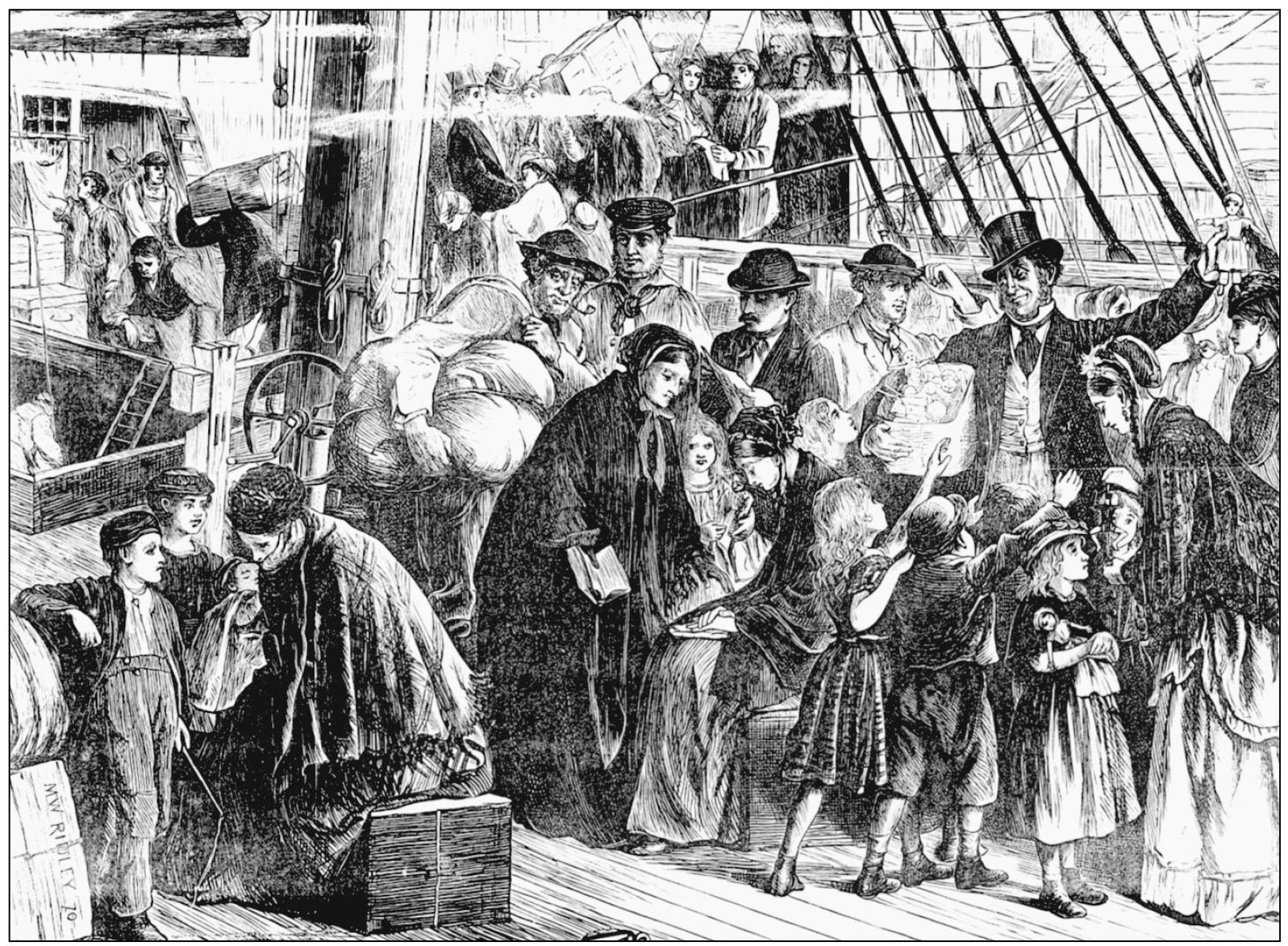

IN AN ENGLISH PORT. Pictured here is a common boarding scene of emigrants as they prepare for their long journey over the seas in the 1800s. To the right, a man is handing out dolls to a crowd of girls; in the center, a matron tries to console a young woman; behind them, more passengers bearing boxes board the ship.

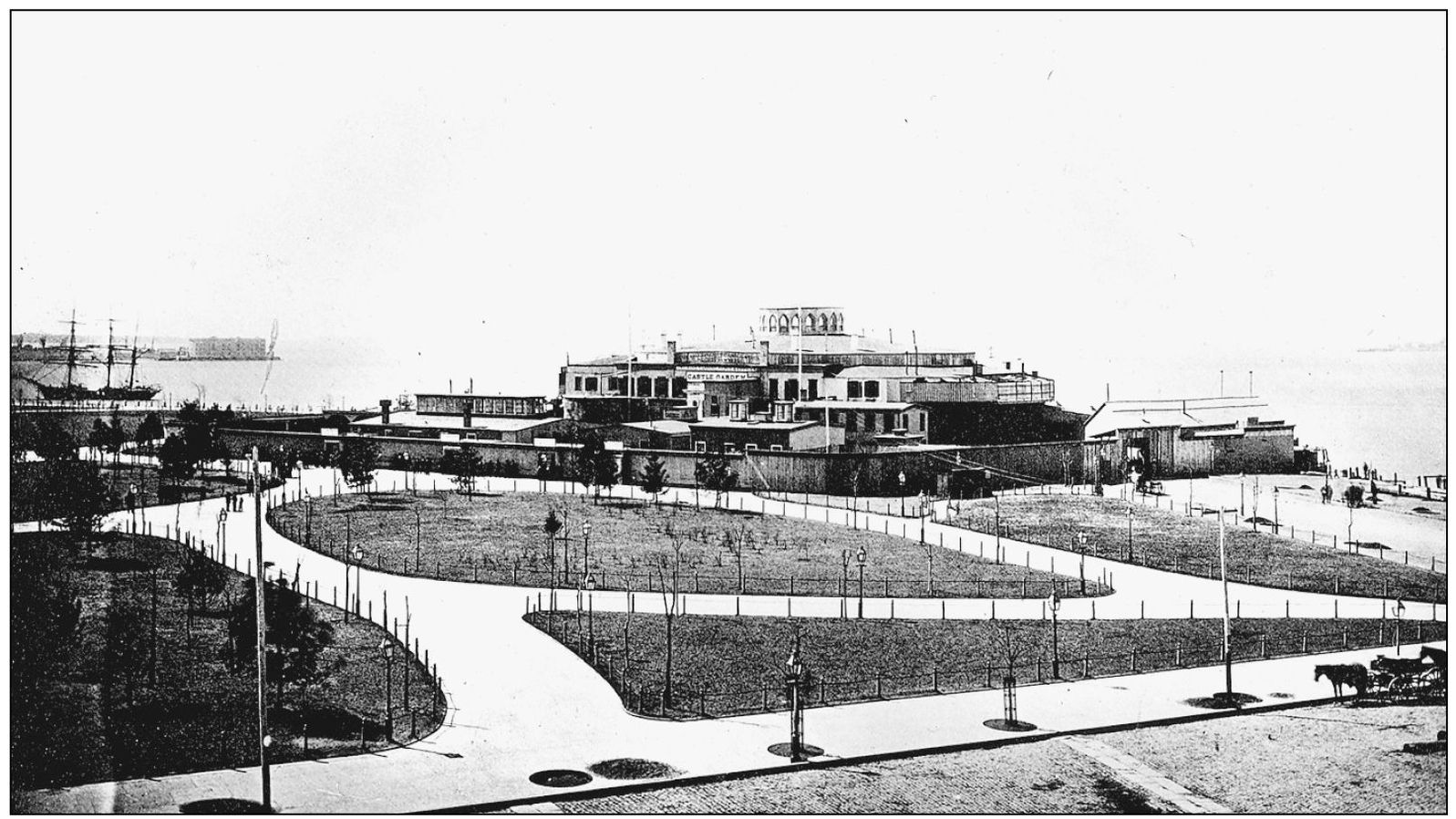

CASTLE GARDEN. This was Americas first immigrant station. Opened in August 1855, it was operated by the government of New York State and became a symbol to European emigrants. By the time it closed in April 1890, some eight million immigrants had passed through its halls. Its top immigrant groups were the Germans, Scandinavians, Irish, English, Scottish, and French. Many became homesteaders in the Midwest or Canada.

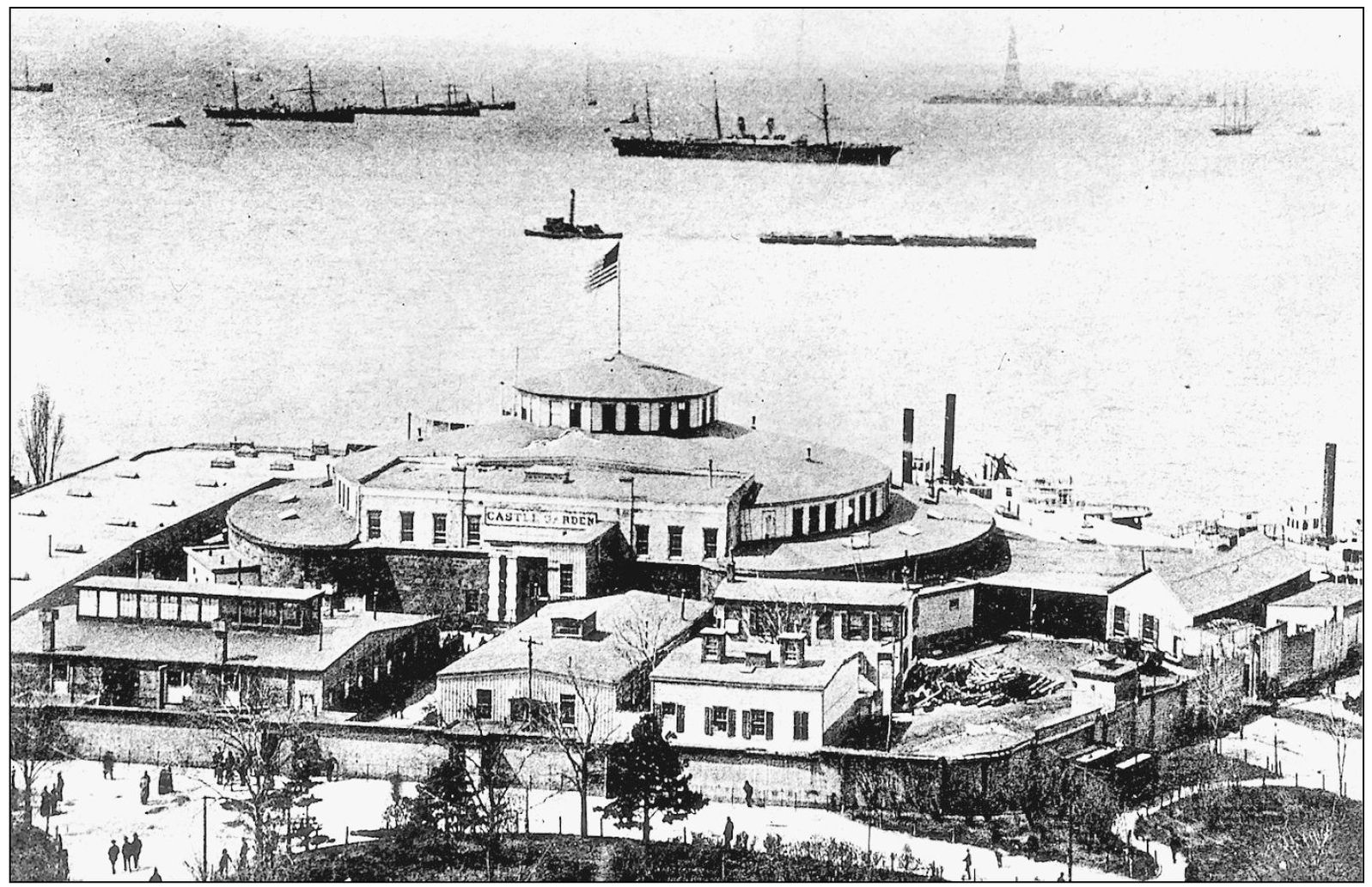

A CLOSER LOOK AT CASTLE GARDEN. Located at the southern tip of Manhattan, Castle Garden was in an ideal location for ships captains to send their foreign passengers for immigration inspection. This c. 1888 view shows the numerous buildings within the complex, such as the infirmary and the intelligence office. The Statue of Liberty can be seen in the distance. A series of scandals eventually forced the station to be closed.

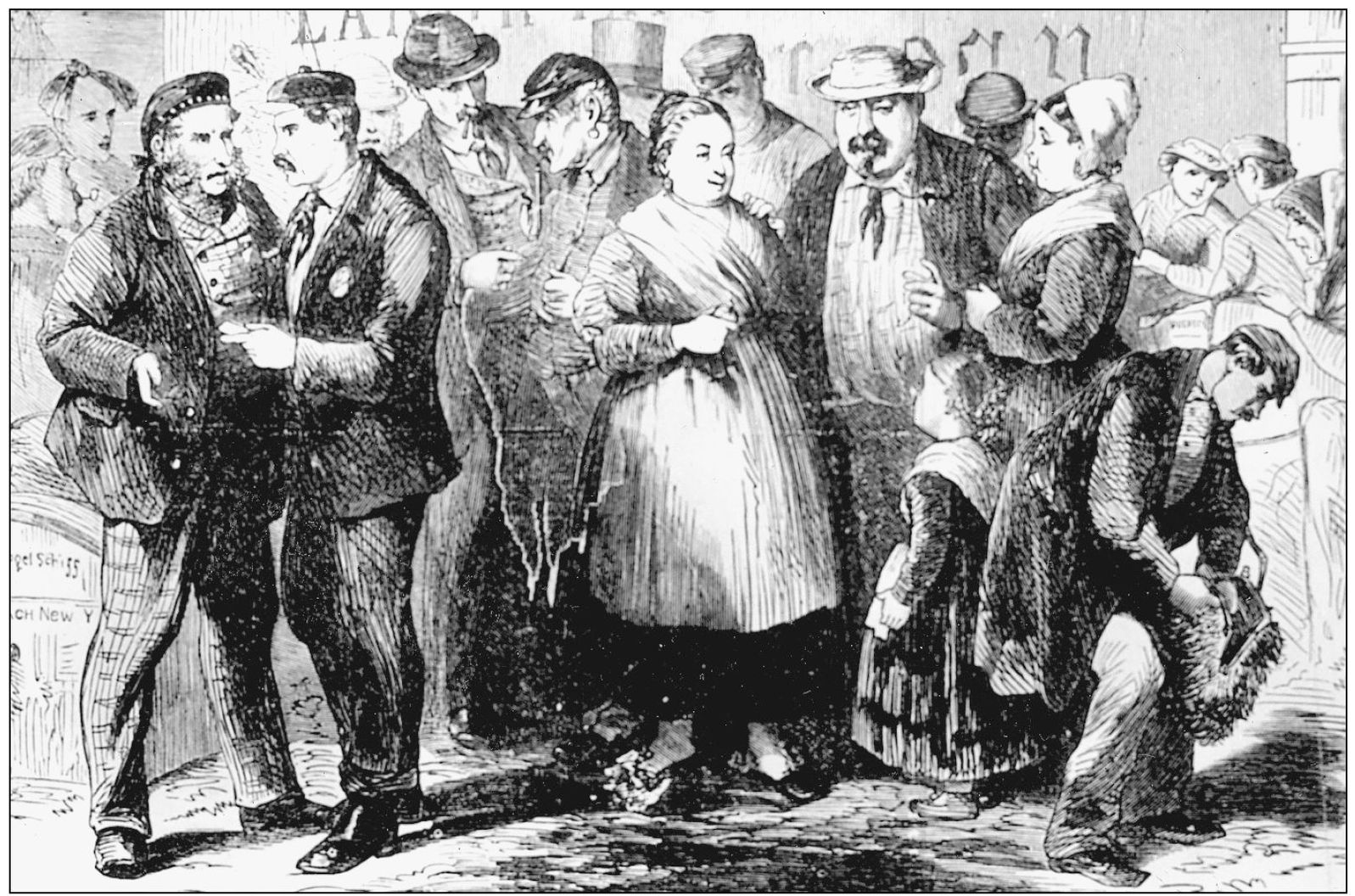

AT THE CASTLE GARDEN LABOR EXCHANGE, THE 1860S. This telling sketch shows a crowd of immigrants looking for work. A Scotsman (left) is standing in front of a German trunk. The others are mainly Germans. All appear calm and have not noticed that a robber (right) is rifling through a womans purse.

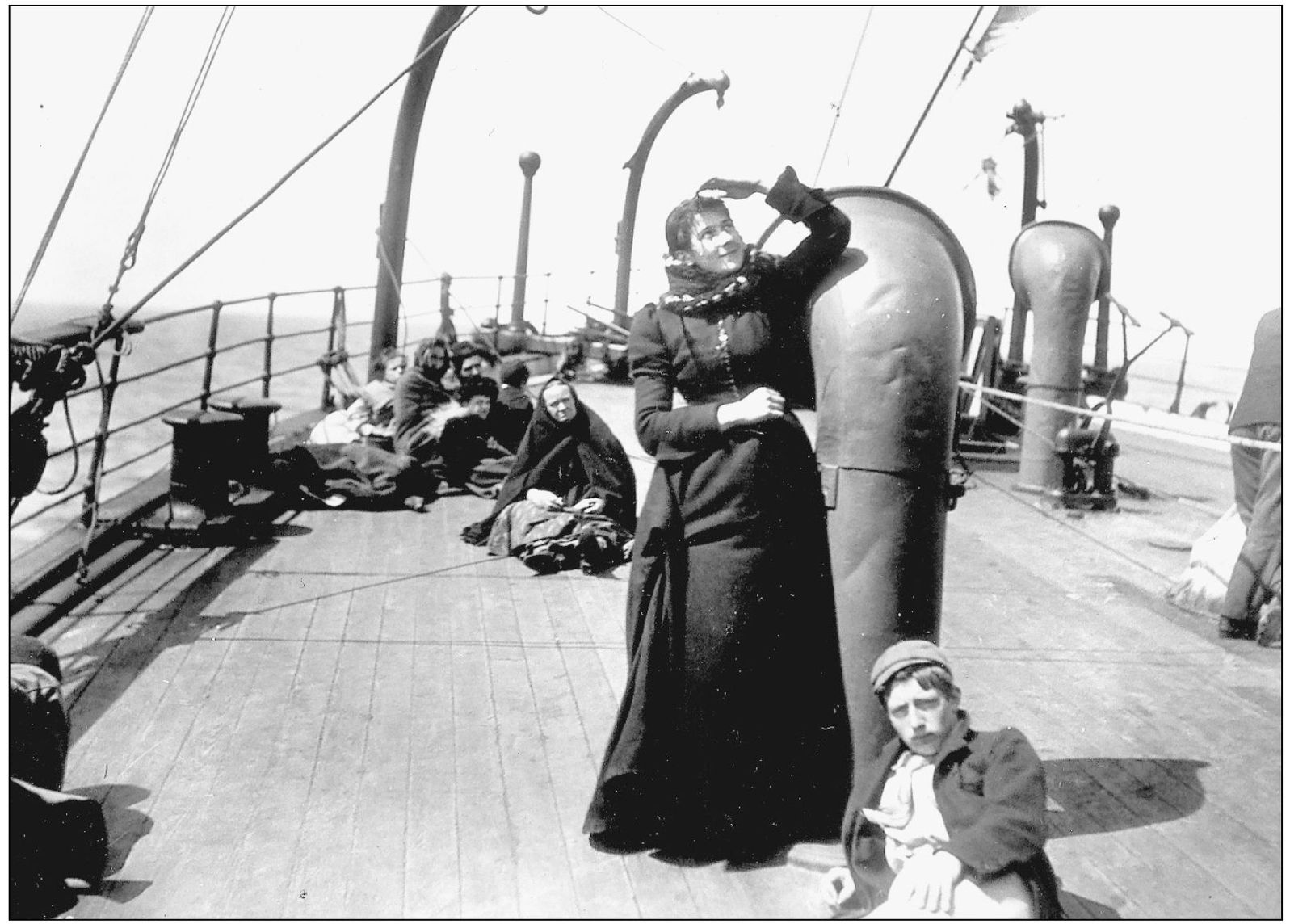

THE OCEAN CROSSING. Joseph Byron snapped this shot of immigrant passengers taking the sun and air on the steerage deck of the steamship Pennland in 1890.

GOOD HUMOR AT SEA. Here, Joseph Byron caught a cheerful moment in the lives of these emigrant passengers of the Pennland. In spite of the sunlight, it is clearly a chilly day on deck.

A GLIMPSE OF THE HEAVENS. In this 1890 view from the Pennland, an immigrant serenely takes a skyward glance as her fellow travelers scowl at the cameraman.

ELLIS ISLAND. Before the Europeans came, the local Native Americans called it Gull Island, or kioshk . There they gathered oysters, clams, and mussels and fished for striped bass and flounder. The Dutch bought the island from the Native Americans in 1630 and named it Little Oyster Island. In 1774, Samuel Ellis (17121794) purchased it. The federal government gained ownership of the island in 1808 and built Fort Gibson there, as seen in this drawing.

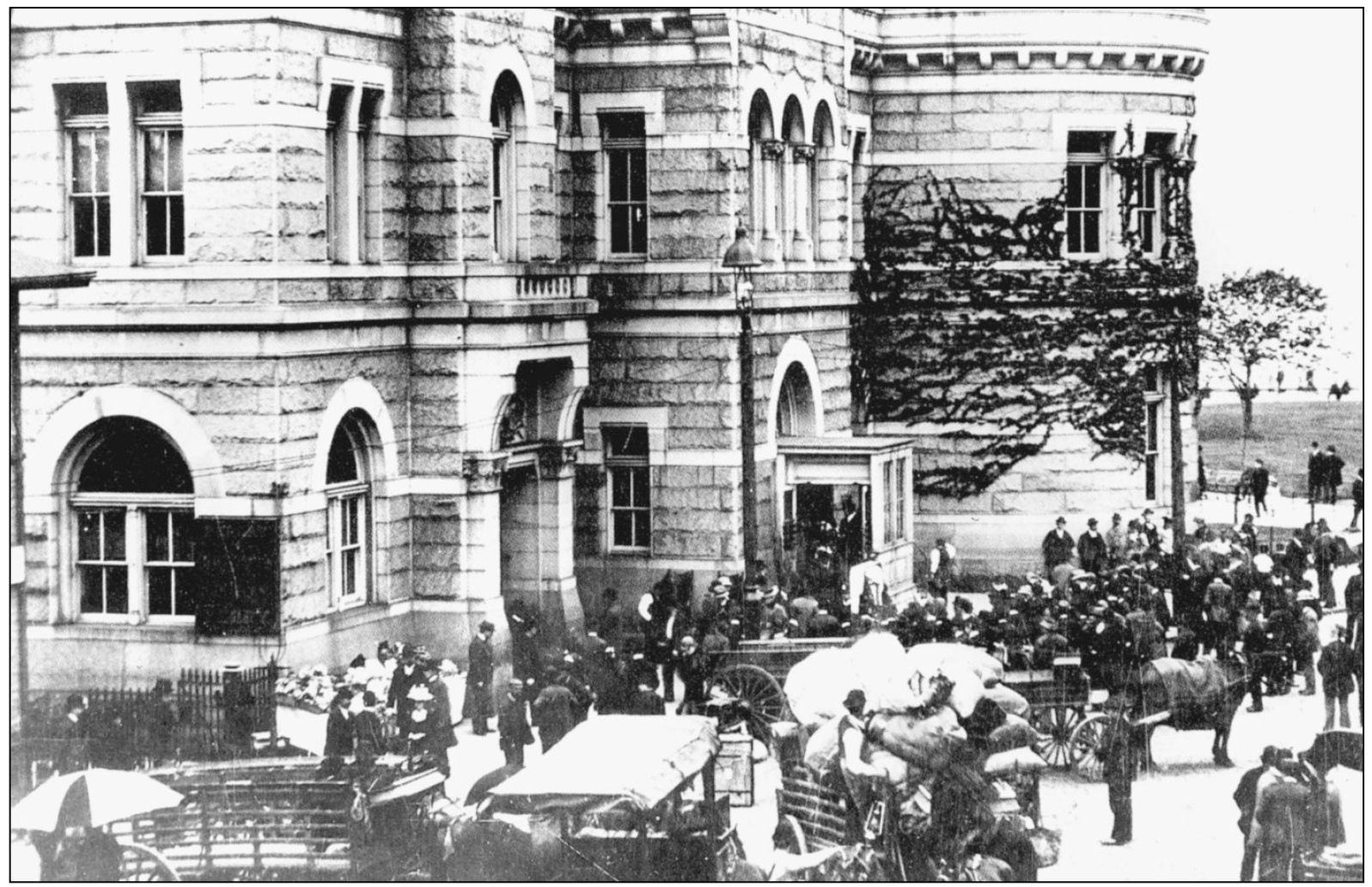

HORSES, WAGONS, AND IMMIGRANTS AT THE BARGE OFFICE. In 1890, Congress and President Harrison chose Ellis Island as the site of the first federally operated immigrant receiving station. While the new station was being built, the government used the barge office, pictured here, as a temporary landing place for immigrants. It was located at the edge of Battery Park and within sight of Castle Garden.