Published by The History Press Charleston, SC 29403 www.historypress.net Copyright 2011 by Barry Moreno All rights reserved Cover illustration courtesy of the National Park Services. First published 2011 e-book edition 2013 Manufactured in the United States ISBN 978.1.62584.209.1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Moreno, Barry. The Ellis Island quiz book / Barry Moreno. p. cm. print edition ISBN 978-1-60949-418-6 1.

Published by The History Press Charleston, SC 29403 www.historypress.net Copyright 2011 by Barry Moreno All rights reserved Cover illustration courtesy of the National Park Services. First published 2011 e-book edition 2013 Manufactured in the United States ISBN 978.1.62584.209.1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Moreno, Barry. The Ellis Island quiz book / Barry Moreno. p. cm. print edition ISBN 978-1-60949-418-6 1.

Ellis Island Immigration Station (N.Y. and N.J.)--Miscellanea. 2. United States--Emigration and immigration--History--Miscellanea. I. Title.

JV6484.M655 2011 304.873--dc23 2011035034 Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. Contents Preface Known to all the world as Americas Golden Door, Ellis Island was the nations principal gateway for millions of hopeful foreigners seeking legal entry into a country that offered hope, opportunity and relative safety from war, famine and violence.

Many an immigrant must have speculated about what the United States was like and what it might have in store for him. One thing is certain: the station itself showed these immigrants the Anglo-Americans form of bureaucracy and his ever-growing attachment to laws of restriction and exclusion. In view of this, it comes as no surprise that the little islandfull of red tape, regimentation and an odd mixture of severity and kindnessgave foreigners an experience they would never forget. Centuries ago, the island had been one of the lands belonging to the native tribes of the Lenape Indians. Here, they gathered sustenance from the islands rich oyster beds, and years later their Dutch and English successors would do the same. For this reason, it came to be known as Little Oyster Island.

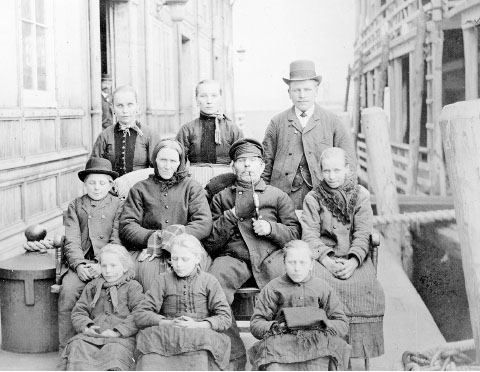

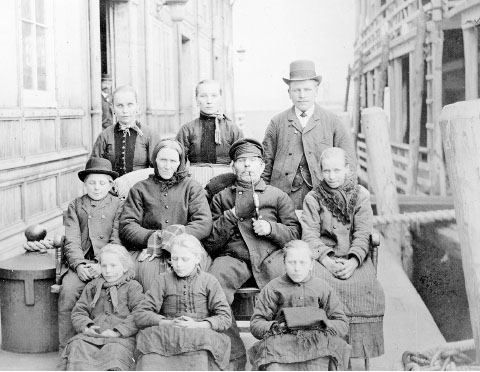

In 1765, the place got a more sinister monikerGibbet Islandafter a pirate was hanged there from a wooden gibbet. Around 1774, Samuel Ellis, a New York City merchant and farmer, bought the property and used it for private commercial ventures. Following his death, his heirsafter a series of family squabblessold it to New York State for the sum of $10,000. The state, fearful of another war with Great Britain, then gave it to the federal government, and a small fortress was constructed on it. Later known as Fort Gibson, it was finished in 1811 and armed with a garrison of artillerymen and fourteen heavy guns.  An immigrant family from the German Grand Duchy of Mecklenburg, October 1890.

An immigrant family from the German Grand Duchy of Mecklenburg, October 1890.

Located in northern Germany, this Protestant part of the Second Reich had a large agricultural population. Many years laterafter the Civil Warthe army left the island to the navy, which stored gunpowder and other explosives there. An outcry against this civil danger to New York and the outlying area finally ended with the munitions being removed in 1890. Throughout the nineteenth century, the United States grew from a set of Atlantic coast states to a vast nation stretching to the Pacific. Part of its rise was stimulated by heavy European immigration, particularly from Germany, Great Britain, Ireland, Holland, Scandinavia and France. These millions were heartily welcome since most of them shared strong cultural, religious and ethnic ties to the dominant Anglo-Saxon population.

Only the rise of massive Irish Catholic immigration during the Irish Potato Famine in the 1840s and the steady flow of Chinese immigrants in the wake of the California Gold Rush caused Protestant America to begin raising objections to the open door policy. In 1855, New York State opened the nations first immigrant landing depot inside Castle Garden, a circular fortress in Manhattans Battery Park; the structure had once served the same purpose as old Fort Gibson on Ellis Island. New York States immigration commissioners made certain that all arriving foreigners were taken to Castle Garden, where they were registered, given medical attention and received advice and help from Christian and Mormon missionaries. In addition, they could buy refreshments, send telegrams, exchange money, write letters to friends, buy train tickets and talk with a variety of clerks, any number of whom could speak in at least one of the common languagesGerman, French, Swedish, Danish, Norwegian, Dutch, Gaelic, Hungarian and Czech. By the 1880s, Castle Garden could barely stand the immigrant crush, while scandals and abuses made the situation even worse. In addition, the federal government came under more and more public pressure to take over immigrant processing and find a way to keep out undesirables, which to most critics meant Chinese immigrants, foreign contracted laborers, convicted criminals, the dangerously ill and immoral persons.

Congress responded by withdrawing the stipend and support it had been giving to the state commissioners. This situation forced New York to close Castle Garden in the spring of 1890 (a few years later, the city fathers remodeled the structure and reopened it as the municipal aquarium). Meanwhile, Congress and President Benjamin Harrison got to work. In April 1890, Ellis Island was chosen as the site of the nations first federally run immigrant depot. The next year, in July 1891, they approved an immigration act creating, among other things, the United States Bureau of Immigration and outlined what sort of immigrants would not be allowed to enter the country. On January 1, 1892, the Ellis Island Immigrant Station was opened.

The festive occasion marked a dramatic shift of policy toward immigrants, one in which scrutiny and selection would now play the cardinal role.  A family of newly arrived Dutch immigrants, 1890. Between 1820 and 1900, approximately 340,000 Dutch people immigrated to the United States.

A family of newly arrived Dutch immigrants, 1890. Between 1820 and 1900, approximately 340,000 Dutch people immigrated to the United States.  A Scottish immigrant family, 1890. Yet in spite of this change of attitude, certain similarities between the two persisted: the daily transfer of immigrants by small steamboats, the checking of baggage, the long lines, cursory medical exams, asking the newcomers personal questions, taking down notes, deciding if anyone ought to be held back for a time and the arranging of boats to get those approved and landed away from the island and into Manhattan or over to the Jersey Shore. Striking differences were also evident.

A Scottish immigrant family, 1890. Yet in spite of this change of attitude, certain similarities between the two persisted: the daily transfer of immigrants by small steamboats, the checking of baggage, the long lines, cursory medical exams, asking the newcomers personal questions, taking down notes, deciding if anyone ought to be held back for a time and the arranging of boats to get those approved and landed away from the island and into Manhattan or over to the Jersey Shore. Striking differences were also evident.

One dramatic change was the adoption of a clearly inquisitorial manner of registering newcomersfor the Bureau of Immigration dispensed with the old Castle Gardentype of registry clerk and promoted the holders of that office to the rank of U.S. Immigrant Inspector. These inspectors were given the authority to examine each entrant and to search out every lie or guilty secret that might help them unmask an undesirable and unsavory foreigner. Thus, hundreds were detained each week and scores were brought before rigid investigative panels known as boards of special inquiry. Furthermore, procedures of exclusion and deportation were set in place and a new form of medical scrutiny was entrusted to military surgeons of the United States Marine Hospital Service. Meanwhile, Ellis Islands first commissioner, John B.

Next page

Published by The History Press Charleston, SC 29403 www.historypress.net Copyright 2011 by Barry Moreno All rights reserved Cover illustration courtesy of the National Park Services. First published 2011 e-book edition 2013 Manufactured in the United States ISBN 978.1.62584.209.1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Moreno, Barry. The Ellis Island quiz book / Barry Moreno. p. cm. print edition ISBN 978-1-60949-418-6 1.

Published by The History Press Charleston, SC 29403 www.historypress.net Copyright 2011 by Barry Moreno All rights reserved Cover illustration courtesy of the National Park Services. First published 2011 e-book edition 2013 Manufactured in the United States ISBN 978.1.62584.209.1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Moreno, Barry. The Ellis Island quiz book / Barry Moreno. p. cm. print edition ISBN 978-1-60949-418-6 1. An immigrant family from the German Grand Duchy of Mecklenburg, October 1890.

An immigrant family from the German Grand Duchy of Mecklenburg, October 1890. A family of newly arrived Dutch immigrants, 1890. Between 1820 and 1900, approximately 340,000 Dutch people immigrated to the United States.

A family of newly arrived Dutch immigrants, 1890. Between 1820 and 1900, approximately 340,000 Dutch people immigrated to the United States.  A Scottish immigrant family, 1890. Yet in spite of this change of attitude, certain similarities between the two persisted: the daily transfer of immigrants by small steamboats, the checking of baggage, the long lines, cursory medical exams, asking the newcomers personal questions, taking down notes, deciding if anyone ought to be held back for a time and the arranging of boats to get those approved and landed away from the island and into Manhattan or over to the Jersey Shore. Striking differences were also evident.

A Scottish immigrant family, 1890. Yet in spite of this change of attitude, certain similarities between the two persisted: the daily transfer of immigrants by small steamboats, the checking of baggage, the long lines, cursory medical exams, asking the newcomers personal questions, taking down notes, deciding if anyone ought to be held back for a time and the arranging of boats to get those approved and landed away from the island and into Manhattan or over to the Jersey Shore. Striking differences were also evident.