www.headofzeus.com

For my son Jack, with love

Contents

When England sets her banner forth

And bids her armour shine,

Shell not forget the famous North,

The lads of moor and Tyne;

And when the loving cups in hand,

And honour leads the cry,

They know not old Northumberland

Wholl pass her memory by.

When Nelson sailed for Trafalgar

With all his countrys best,

He held them dear as brothers are,

But one beyond the rest.

For when the fleet with heroes manned

To clear the decks began,

The boast of old Northumberland

He sent to lead the van.

Himself by Victory s bulwarks stood

And cheered to see the sight;

That noble fellow Collingwood,

How bold he goes to fight!

Love, that the league of Ocean spanned,

Heard him as face to face;

What would he give, Northumberland,

To share our pride of place?

The flag that goes the world around

And flaps on every breeze

Has never gladdened fairer ground

Or kinder hearts than these.

So when the loving cups in hand

And honour leads the cry,

They know not old Northumberland,

Wholl pass her memory by.

Sir Henry Newbolt

The Collingwood touch

Visitors to Menorca arriving in vast eight-decker cruise ships at the islands main harbour, Port Mahon, are disgorged at the bottom of the cliff on which the town perches. It is one of the great maritime arrivals. To reach the town, and for a magnificent view back across the harbour, they must climb a broad stone staircase which for three centuries has been called Pigtail Steps, after the hairstyles of generations of English sailors. At the beginning of Patrick OBrians novel Master and Commander, these are the steps from which Jack Aubrey looks out in vain to catch a glimpse of the Sophie, his first command.

This was where Sophie s real-life counterpart, a tiny 14-gun sloop called Speedy, brought her famous prize, the 32-gun xebec frigate Gamo, in 1801, shortly before peace broke out in the Mediterranean and Menorca was returned to Spanish control after a century of British domination. Even today, the bars that line the waterfront have an air of the English navy about them: their massive timber roofs remind one of the tween decks of a first-rate ship of the line, and their walls are made of bricks brought out from England as ships ballast. Most tourists come to Menorca for the reliable summer climate; some stay on and brave winter storms: the tramontana and the mistral. Few miss Mahons peculiarly attractive hybrid architecture which lends it an atmosphere of eighteenth-century Portsmouth crossed with Catalan baroque: the town that gave the world mayonnaise.

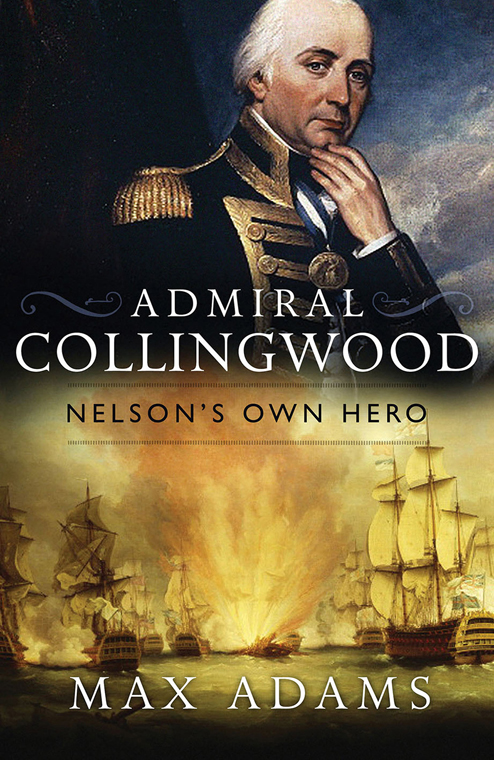

Of the many English visitors who come here every year, a small number regularly book rooms at Collingwood House, a respectable establishment lying a mile out from the busy town centre just off the road to Es Castell, at the end of a drive whose palm trees shade it from the worst of the midday sun. Fransisco Pons Mantonari, an educated man from very old Menorquin stock, has owned Collingwood House for more than forty years. When he came across the place in 1961, in the days before package holidays were generally affordable, it had been owned by the German sculptor Waldemar Fenn, and was in a lamentable state: its reconstruction has been a labour of love. Little of the original furnishing remained, and its current comforts represent a lifes work. After decades of Fascist rule all records and deeds had been lost, and only local oral tradition was left to permit the association with Admiral Lord Collingwood: battle commander, diplomat, wit and bosom friend and hero of Nelson. Eventually, however, an old military map turned up which showed that the house had been called Collingwood House at least as early as 1813. So Mantonari called his new business the Hotel del Almirante, but kept its English name too.

Today, restored to Anglo-Balearic splendour, this house overlooking the deep waters of Mahon harbour is a cliff-top shrine to an English naval officer and statesman largely neglected by posterity. It attracts not just genteel couples of a certain age, but also enthusiasts of naval history. Every Thursday morning during the season Mantonari, accompanied by the magnificent red macaw which sits complacently on his shoulder, gives guided tours of the hotel for guests, and anyone else who is interested. At a quarter-past ten, a small crowd gathers under a sign outside which is painted with a likeness of Collingwood holding his telescope, but looks as though it ought to read Admiral Benbow. Once inside, one could be forgiven for thinking this was somewhere in Devon or Cornwall: there is dark polished oak panelling, and thick carpet on the floor. A pendulum clock ticks.

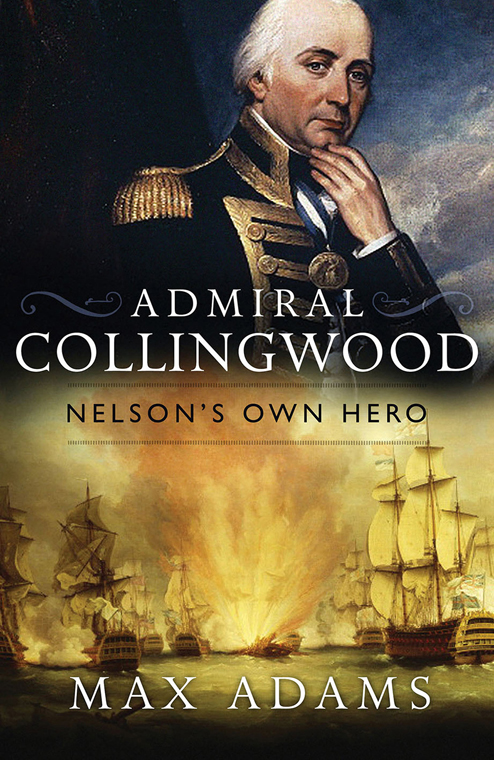

Mantonari is a seasoned performer. As he guides visitors through the foyer, past an original letter of Collingwoods hanging on the wall (cunningly framed with glass both front and back on a hinged mount) he nods at a portrait of Nelson which overlooks the bottom of the stairs: an engraving of the tragic hero writing his last letter to Emma Hamilton before Trafalgar. Mantonari pretends not to allow the name of Nelson to be spoken in his hotel; and laughs. Next to Nelson is a picture of Collingwood. It doesnt have the melodrama of the Nelson portrait. Collingwood was not a melodramatic man. His portraits suggest a stern, if kindly, headmaster, with flowing white hair and piercing eyes that might be about to laugh or to admonish. Stripped of his uniform and medals he might even pass for a notary, or a family doctor. It is hard to imagine him screaming Fire! at his gun crews in the midst of battle. He holds his chin in one hand, with a telescope under his other arm. The telescope might symbolise a memory of his obituarist: Collingwoods grey hair streaming to the wind with eyes like an eagles, on the watch. The real telescope, still in the possession of his family, was no show-piece: it has been repaired with an oilcloth and tar bandage, and the lenses are clouded with the salt spray of the Mediterranean. The hand on the chin is there not to make him look thoughtful, which he does anyway, but to hide a fold of flesh that sagged increasingly as he aged: a man old before his time.

Biographers of Nelson have tended to paint the relationship between the two men as a sort of Holmes-Watson partnership, with Collingwood cast as the doughty but dull Watson to Nelsons brilliant Holmes. Holmes might be an appropriate fictional double for Nelson: a bold, sometimes erratic, passionate genius, capable of inspiring adoration in both men and women; but Collingwood is hopelessly miscast as Watson. He was a better seaman than Nelson, a subtler diplomat, and despite his conservative politics, a naval reformer at least fifty years ahead of his time. What Collingwood lacked, and admired above all else in his friend, was the irresistible Nelsonian impetuosity that allowed his enemy no time to recover once he had made a mistake: Englands Saviour had himself, with typical immodesty, called it the Nelson touch. If there is a fictional counterpart to Collingwood, it is Jack Aubrey, Patrick OBrians very human English epitome.

Next page