President Abraham Lincoln delivering his second inaugural address, March 4, 1865.

ADDITIONAL PRAISE FOR

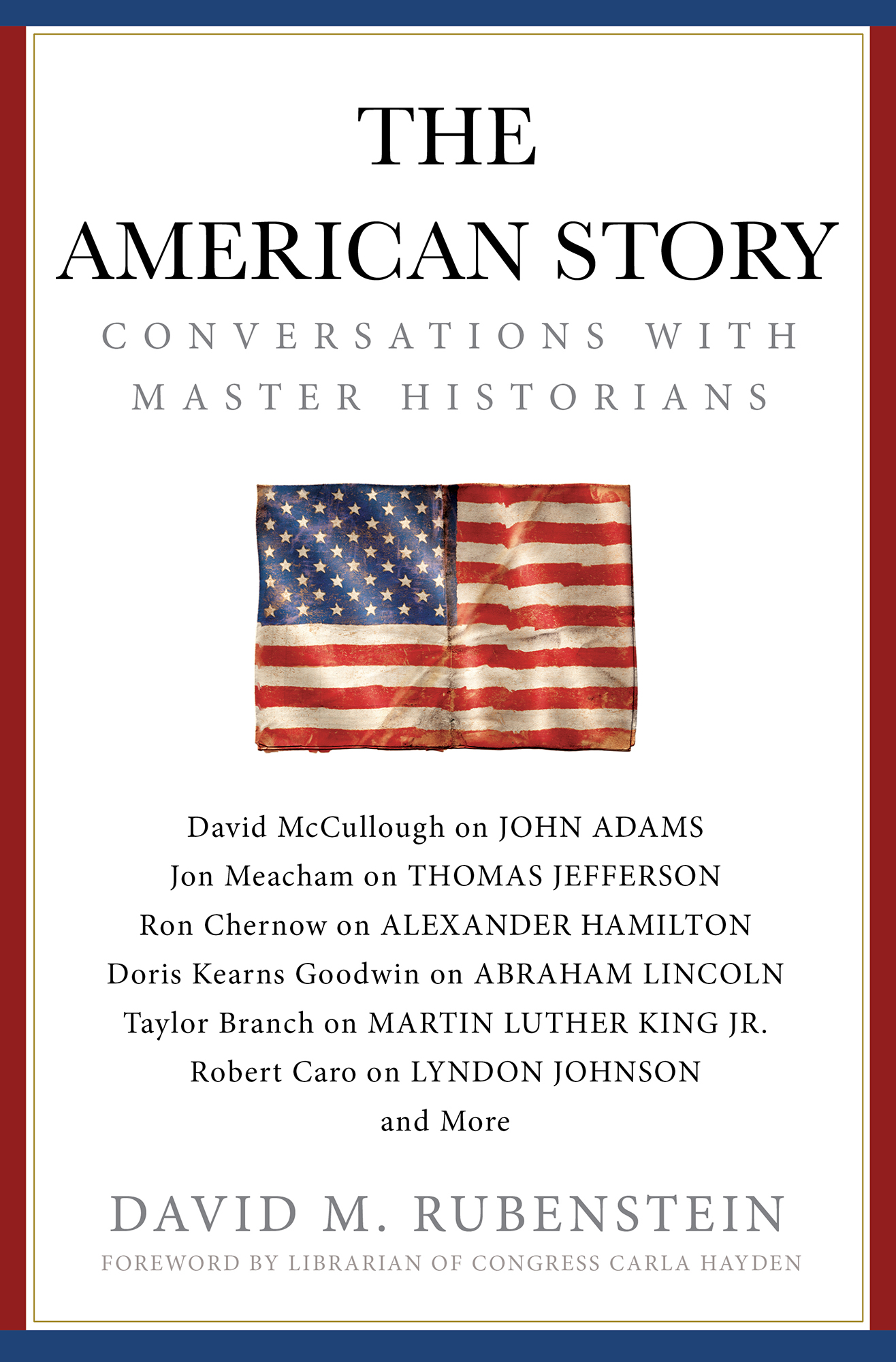

THE AMERICAN STORY

Davids boundless curiosity and lifelong interest in American history make him an ideal choice to interview our nations foremost historians. The lessons in The American Story are as timeless as they are timely.

Lonnie G. Bunch III, secretary of the Smithsonian Institution

The American Story is yet another of Davids patriotic, philanthropic gifts to our country, its history, and its citizens. Its his enthusiasm that I admire most and that drives these important conversations.

Mike Krzyzewski, head coach, Duke mens basketball

History matters, and these engaging and enlightening conversations show why. David Rubenstein deserves a medalas a knowledgeable, incisive, and witty interlocutor, but also as the creator of these Congressional Dialogues, which present the insights of the past to those responsible for the future.

Drew Gilpin Faust, 28th president of Harvard

To Alexa, Ellie, and Andrew, and the teachers of American history and civics

FOREWORD

As Librarian of Congress, I am frequently asked two questions that are similar but come from diametrically opposed assumptions. First, Is the Library of Congress only for members of Congress? And second, Do members of Congress actually use the Library?

The answer to the first is, no, the Library of Congress is for everyoneand I hope everyone reading this will visit (there is plenty to visit online, even if you cant come to Washington). The answer to the second is a resounding yes, members of Congress use the Library, and they use it all the time and in many different ways.

Members have access to a unit of dedicated experts who provide nonpartisan research and analysis, fielding thousands of queries every year. Members check out books by the thousands. And members use the Librarys physical spaces for all kinds of activities. As well, the Library hosts many programs throughout the yearsome for broader audiences and some just for members of Congress.

It is in support of our mission to provide information to Congress that the Library has hosted the Congressional Dialogues series. These events are an opportunity for members to come to the Library for an evening built around the study of individuals who have been significant in American history. They feature treasures from the Library collections related to the individuals and topic, illuminated by our historians and curatorsand, of course, the main event, a conversation with biographers and historians who have studied and written acclaimed works about these figures. Members have the opportunity to listen, ask questions, and dialogue with the guest author and with each othera rare opportunity for bipartisan gathering and learning.

I have learned something too, on every one of these occasions. In part that is due to the exceptional interviewer who moderates and asks questions of each guest author, David M. Rubenstein. David is a remarkable person for many reasons. He describes his approach to charitable giving as patriotic philanthropy. But dont think he has simply coined a phrase. His actions bear this out, in extraordinary ways. In addition to his support of the Library of Congress and its programs, including the National Book Festival, he has made historic contributions to the National Archives, restored the Washington Monument, mounted the panda program at the National Zoo, and too many other endeavors to fully chronicle here. In addition to all this, David and I share a voracious love of reading. It is his reading and preparation that help make these conversations insightful, spirited, and memorable.

Which brings me back to the first question about whether the Library is only for members of Congress. While these sessions are, in fact, for Congress, I am grateful to David for his vision in sharing the portion of these programs devoted to his discussion with the authors. In these pages you will find thoughtful exchanges about some of the giants in historywhat motivated them, what scared them, what inspired them? It is my hope you will be inspired as well, to read some of these books in their entirety and expand your understanding of the shared history of our nation.

Carla Hayden

14th Librarian of Congress

INTRODUCTION

The American story is one that surely could not have been foreseen by those who helped to create the United States in 1776, when the Declaration of Independence was adopted, or in 1787, when the Constitution was created.

Who then could have predicted that thirteen colonies would evolve, with many starts and fits, into the worlds largest economy, most powerful military force, leading political power, and alsofor so manya leading symbol of liberty, freedom, and justice?

Who then could have predicted that so many extraordinary leadersmen and women, from all kinds of backgrounds, with so many different types of skills and talentswould emerge to create the American story? Who then could have predicted how hard it would be, more than two hundred years later, to convey the depth and breadth of that story to those interested in learning how the United States evolved?

This book is designed, through interviews with leading American historians, to provide a glimpse into the American story.

Why is it so important to know about history?

George Santayana, a Spanish-born Harvard professor of philosophy (among many other subjects), may have said it best: Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it. In other words, a knowledge of history is likely to help individuals, and perhaps especially policymakers, to avoid the mistakes of the past, and thereby, one hopes, make better decisions about the future.

To be sure, life (and policymaking) is more complicated than that. Those steeped in a knowledge of history do not always make perfect decisions.

Still, having such knowledge improves the chances of avoiding the mistakes of the past. One of the best ways to acquire it is to read and learn from the painstaking, laborious, read-the-original-documents work of historians. Alfred Nobel did not create a history prize, but that oversight should not be taken to mean that the work of historians in educating us about the past (and, in effect, about the future) is less significant than the work of those who do win Nobel Prizes.

My lifelong interest in history may stem from several factors. Perhaps it came about because my grades in history were better than my other grades, or perhaps because I was fortunate at a young age to work on Capitol Hill and in the White Housetwo places at the center of American history. Or perhaps because I became involved with trying to preserve historic documents and historic buildings.

After college at Duke University and law school at the University of Chicago, I practiced law in New York, worked for the late Senator Birch Bayh of Indiana and President Jimmy Carter, and then practiced law in Washington, D.C. My career did not lead anyone to think that I had the skill set or background to enter the investment world. Most especially was that true of my mother, who thought I should always keep my law license in case my investment efforts went south. And, to please her, I have remained to this day a member of the D.C. Bar.