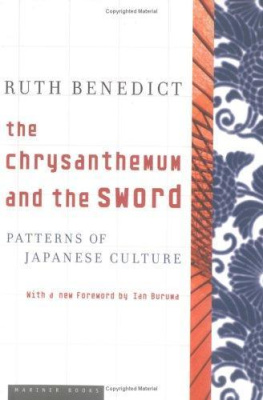

First Mariner Books edition 2005

Copyright 1946 by Ruth Benedict

Copyright renewed 1974 by Donald G. Freeman

Foreword copyright 2005 by Ian Buruma

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

www.hmhco.com

The Library of Congress has cataloged the print edition as follows:

Benedict, Ruth, 18871948.

The chrysanthemum and the sword.

Reprint. Originally published: Cleveland: Meridian Books, 1967.

Includes index.

1. JapanCivilization. 2. National characteristics, Japanese. I. Title.

DS821.B46 1989 952 88-34818

ISBN -13: 978-0-618-61959-7

ISBN -10: 0-618-61959-3

e ISBN 978-0-547-52514-3

v4.0515

The author wishes to thank the publishers who have given her permission to quote from their publications: D. Appleton-Century Company, Inc., for permission to quote from Behind the Face of Japan, by Upton Close; Edward Arnold and Company for permission to quote from Japanese Buddhism, by Sir Charles Eliot; The John Day Company, Inc., for permission to quote from My Narrow Isle, by Sumie Mishima; J. M. Dent and Sons, Ltd., for permission to quote from Life and Thought of Japan, by Yoshisabura Okakura; Doubleday and Company for permission to quote from A Daughter of the Samurai, by Etsu Inagaki Sugimoto; Penguin Books, Inc., and the Infantry Journal for permission to quote from an article by Colonel Harold Doud in How the Jap Army Fights; Jarrolds Publishers (London), Ltd., for permission to quote from True Face of Japan, by K. Nohara; The Macmillan Company for permission to quote from Buddhist Sects of Japan, by E. Oberlin Steinilber, and from Japan: An Attempt at Interpretation, by Lafcadio Hearn; Rinehart and Company, Inc., for permission to quote from Japanese Nation, by John F. Embree; and The University of Chicago Press for permission to quote from Suye Mura, by John F. Embree.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Japanese men and women who had been born or educated in Japan and who were living in the United States during the war years were placed in a most difficult position. They were distrusted by many Americans. I take special pleasure, therefore, in testifying to their help and kindness during the time when I was gathering the material for this book. My thanks are due them in very special measure. I am especially grateful to my wartime colleague, Robert Hashima. Born in this country, brought up in Japan, he chose to return to the United States in 1941. He was interned in a War Relocation Camp, and I met him when he came to Washington to work in the war agencies of the United States.

My thanks are also due to the Office of War Information, which gave me the assignment on which I report in this book, and especially to Professor George E. Taylor, Deputy Director for the Far East, and to Commander Alexander H. Leighton, MC-USNR, who headed the Foreign Morale Analysis Division.

I wish to thank also those who have read this book in whole or in part: Commander Leighton, Professor Clyde Kluckhohn and Dr. Nathan Leites, all of whom were in the Office of War Information during the time I was working on Japan and who assisted in many ways; Professor Conrad Arensberg, Dr. Margaret Mead, Gregory Bateson and E. H. Norman. I am grateful to all of them for suggestions and help.

RUTH BENEDICT

Foreword to the Mariner Books Edition

by Ian Buruma

T O UNDERSTAND another culture is hard at the best of times. You need, as Ruth Benedict says, the tough-mindedness to recognize differences, even when they are disturbing. The world is not one sentimental brotherhood in which we are all really the same under the surface. Individuals have different perspectives, formed by particular interests, histories, experiences. If this is true of individuals, it would be odd if something similar did not apply to nations. More important, though, for a student of other cultures is what Benedict calls a certain generositythe generosity, that is, to see that other perspectives, even if they go against our own views, can have a validity of their own. A zealot cannot be a good cultural anthropologist.

To understand ones enemy in the midst of a brutal conflict requires an unusual amount of that generosity. But it is more necessary than ever, for only an objective assessment of the enemys strengths and weaknesses can be of any possible use. When Ruth Benedict was commissioned by the U.S. government to write a cultural analysis of the Japanese in June 1944, it would have been easy, and totally worthless, to confirm American prejudices about that still remote and largely unknown people.

Such prejudices were adequately catered to already in wartime propaganda. The Japs were born fanatics, treacherous, and uncivilized. They were monkey men, savages, rats, mad dogs, or crazed samurai, as ready to kill themselves as others. To tame this brutal race, it was necessary, as the Sydney Daily Telegraph opined in 1945, to lift across 2000 years of backwardness... a mind which, below its surface understanding of the technical knowledge our civilisation has produced, is as barbaric as the savage who fights with a club and believes thunder is the voice of his God.

Benedict had to cut through all that nonsense to come up with an account that would allow the Allied leaders to predict with some degree of accuracy how the Japanese would behave; whether they would surrender or fight to the last man, woman, and child; what it would take to end the war; how to deal with the Emperor; what to expect in a Japan under Allied occupation, and so on. Writing such an account in 1944 would have been difficult enough for an expert who had lived in Japan for many years. Benedict, as she herself explains, was not an expert, had never been to Japan, and had to rely on written materialanything from academic books to Japanese novels in translationas well as movies and interviews with Japanese Americans.

To be an expert is not necessarily an advantage, however. Experts sometimes have rather inflexible views and are disinclined to let new developments or ideas disturb the comfort of their expertise. Joseph Grew, for example, an old Japan hand who had served as U.S. ambassador in Tokyo before the Pacific war, was convinced that the Japanese were essentially an irrational people and could never adapt to democratic government. One of the great merits of Ruth Benedict was her staunch resistance to racial and cultural prejudices. She came to her study with an open mind.

One might disagree, of course, with the premise of classical cultural anthropology, which is that such a thing as national character exists. It is not a fashionable notion these days. Pseudoscientific theories of race and nation have tainted any idea of essentializing collective characteristics. Theorists now prefer to stress hybridity or the multicultural aspects of nations rather than think in terms of monocultural identities. Yet at the same time we are obsessed with our identities. Indeed, perhaps because of the uncertainties of living in multicultural societies plugged into a global economy, we cannot get enough of ourselves. Books on national heroes, national values, and national histories are selling briskly everywhere.

National navel-gazing was precisely the opposite of what Ruth Benedict was doing. Such narcissism would have made her enterprise impossible. She was truly interested in the Other. The question is whether the contours and characteristics of that Other were as clear as she made them out to be.

I have had my doubts about cultural interpretations of political affairs and expressed skepticism in the past about the distinction, made famous by Ruth Benedict, between shame cultures and guilt cultures. The risk of cultural analysis is that it assumes a world that is both too static and too uniform. Benedict was well aware of this danger. But while acknowledging the many changes that affect a nation or culture over time, she did believe in the tenaciousness of certain patterns. As she says about the English, it was just because they were so much themselves that different standards and different moods could assert themselves in different generations.

Next page