For Kathleen OShea

Contents

Guide

A s I crossed Guatemalas largest lake and approached the village of Izabal, it was almost impossible to imagine that this loose collection of cinder-block houses and scattered huts was once the chief port of entry to nineteenth-century Central America. The walled army garrison that stood watch on the brow of the hill was now a tumble of stones, the main plaza an exhausted soccer field, and the tombs and markers of the ports cemetery were overgrown and buried.

I had come to the village to see for myself the place where two men came ashore in 1839 and altered the worlds understanding of human history. In some ways, John Lloyd Stephens and Frederick Catherwood were a mismatch, an unlikely pair for such a revolutionary journey. One was a red-bearded, gregarious New York lawyer; the other a tight-lipped, clean-shaven English architect and businessman. But their earlier, separate travels through the ancient ruins of Greece, Palestine, and Egypt had prepared them for the unusual archaeological foray they were about to undertake. And their brilliant, perfectly matched skillsStephens with words and Catherwood with illustrationsmade them ideal candidates to record and make sense of their impending discoveries.

I had picked the same week in the year they had landed 170 years earlier. It was near the end of the rainy season, and I wilted under the same kind of oppressive, stifling heat they had described. If time had long passed the town of Izabal byGuatemalas major Caribbean port was now a hundred miles to the northeastthe surrounding landscape had not changed. The mountain ridge backing the town remained a barrier to the interior, its rain-soaked slopes still coated with dense jungle. As they had for generations, the local people, many occupying palm-thatched huts, still lived close to the earth, nurtured by subsistence tropical agriculture and fish from the lake.

Stephens and Catherwood would lead me on a 1,500-mile chase through the mountains and jungles of Guatemala, Honduras, and Mexico. Where they had traveled on the backs of mules, I would follow in my own primitive beast, a mottled blue 1985 Toyota Corolla sans radio and air-conditioning. Where they complained of problems with muleteers and fretted over the health of their animals, I, driving alone down rutted, bone-cracking gravel and mud jungle roads, envisioned the team of workers on a Japanese assembly line tightening the bolts on my Toyota twenty years earlier and prayed they had done a good job.

For all the rough similarities between our journeys through Central America, I had arrived at Izabal in a world already changed by Stephens and Catherwoods discoveries. The two men fought their way through the thickest of junglesoften only to discover incomprehensible piles of carved stones and mysterious, seemingly inchoate structures. I, on the other hand, would arrive at fully excavated and restored archaeological sites filled with magnificent pyramids, temples, and palaces, sites whose art and hieroglyphics reveal a civilization of extraordinary sophistication and complexity. And while I knew what drove me on my journeyan overpowering desire to learn who these two men were and how they survived against seemingly impossible oddsI did not yet understand the insatiable yearning that drove them to undertake such a crazed and dangerous mission.

Nor did I comprehend the world they had brought with them, carried in their heads. When they arrived, Charles Darwin was still twenty years from publishing On the Origin of Species. In the West, the Bible was still the basic template of history, and most Christians believed the world was less than six thousand years old. The natives found populating the New World when Columbus and his European successors showed up were considered unrefined savages: sparse and scattered Indian tribes who had never more than scratched out a bare subsistence from the land; idol worshippers who performed bloody human sacrifice atop stone mounds.

After 1839, this worldview, the notion that the Americas had always been a land occupied by primitive, inferior people, would change forever. And so would the assumption that writing, mathematics, astronomy, art, monumental architecturecivilization itselfwas only possible through so-called diffusion from within one part of the Old World to another, and from the civilized Old World to the uncivilized New. Stephens and Catherwoods historic journey radically altered our understanding of human evolution. In their wake, it became possible to comprehend civilization as an inherent trait of human cultural progress, perhaps coded into our genes; a characteristic that allows advanced societies to grow out of primitive ones, organically, separately, and without contact, as occurred in Central America and the Western Hemisphere, which were isolated from the rest of the world for more than fifteen thousand years. And, just as with the Old Worlds ancient civilizations, they can collapse, too, leaving behind only remnants of their previous splendor.

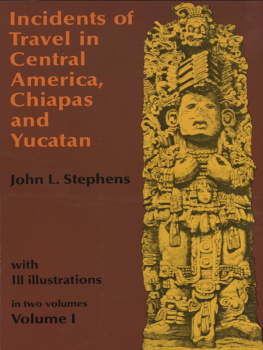

Stephens and Catherwood plunged headlong into a region racked by civil war. They endured relentless bouts of tropical fever, close calls, and physical hardships, and emerged to publish two bestsellers: the first works of American archaeology, so enchantingly written and illustrated that they have become classics and remain in print today. In 1839, they found the remains of what would come to be known as the Maya civilization. More than discovering them, they made sense of them, reaching conclusions that defied the conventional thinking of their time and initiated a century and a half of excavations and investigations, which continue today. After publication of their books, the mysterious stone ruins in Central America, the vast, sophisticated road network of the Inca in South America, and the monuments and temples of the Aztecs could no longer be viewed as vestiges of the Lost Tribes of Israel, the ancient seafaring Phoenicians, or the survivors of lost Atlantis. They were understood to be solely indigenous in origin, the products of the imagination, intelligence, and creativity of Native Americans.

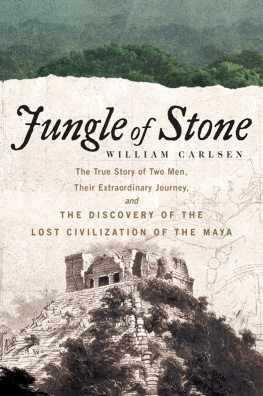

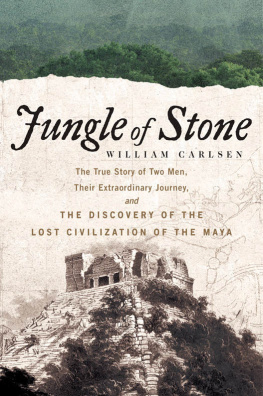

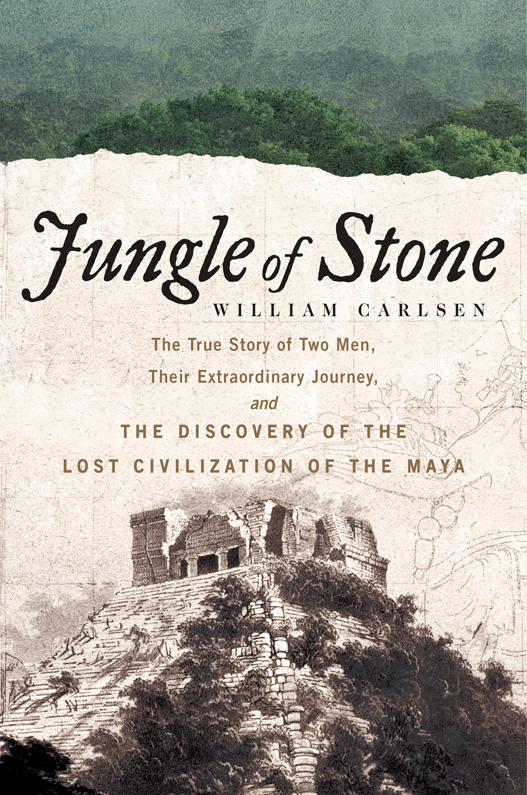

Jungle of Stone tells of the harrowing journey that led to these discoveries and the two extraordinary men who made it. The book weaves their little-known biographies through the narrative of their expeditions and their significant achievements afterward. Stephens would best the British Empire twice, and his successes personified the spirit of America on the rise in the nineteenth century.

The book is the first text to combine the history of prior explorations, the circumstances and context of their discoveries, and their sudden and unexpected race with the British to be the first to show the world the art and architectural wonders of the Maya. Catherwoods illustrations, drawn on the spot, are the first accurate, strikingly detailed representations of this lost world from a time before photography.

Even in a great age of exploration that would later reveal the source of the Nile in Central Africa and Machu Picchu in Peru, send expeditions to the north and south poles, Stephens and Catherwood stand apart. Known among archaeologists today as the originators of Maya studies, they accomplished much more. Like Darwin to come, they broke through dogmatic constructions of the past and helped lay the foundation for a new science of archaeology. They captured the romance, mystery, and exhilaration of discovery with a vividness and intensity that inspired the explorers of the future. And they opened to the world a realm of artistic and cultural riches of an ancient American Indian civilization whose remains stagger the imagination, draw millions of visitors every yearand still have much to teach us.