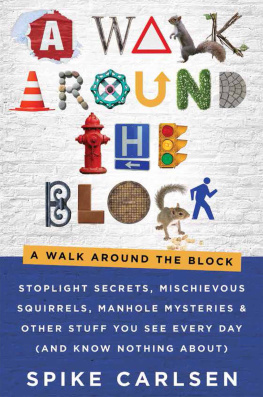

WHY AM IILLITERATE IN FRENCH AND IGNORANT OF LAW crouched beside a stranger, spray-painting my name on a Paris alley wall? Why am I stumbling around a two-hundred-year-old sewer exploring sludge and rats? Why am I interviewing a squirrel linguist? Surely there are more legal, less olfactorily offensive ways to find out about the world outside my front door.

I can only blame it on one bitterly cold morning a few years back. I had shuffled into the bathroom and turned on the water to brush my teeth. Nada. In a fog, I trudged to the kitchen faucet hoping for better. Nope. My next shuffle was to my phone to call my city water department. The voice that answered was that of someone whod already answered the phone one too many times that morning. Halfway through my first sentence, the voice sighed. Ill put you through to Robert.

This is the fifth call weve gotten from people in your part of town this morning, Robert said. Your water service line is frozen.

This was impossible. This is America. This is the twenty-first century. This is The Land of 10,000 Lakes.

Robert explained there was only one company that could remedy the problem, and it was booked for two days.

This too seemed impossible.

Two days later, a sleep-deprived worker from Miller Excavating showed up in a flatbed truck with a massive gas-powered arc welder crouched on the bed. He snaked one end of a long cable down the basement stairs and attached it to a pipe coming out of the floor. Then he went out to our driveway, kicked around in the snow until he found a hockey pucksize disk, and attached another cable. He told me to turn on our kitchen faucet, then fired up the arc welder and a Marlboro Light. He explained the welder was feeding current through one cable, using the metal water line to conduct current to the other cable, thus generating heat andhopefullythawing the water line. Two cigarettes later, the faucet burped and a string, then a rope, then a flush of water emerged. Then I wrote a check for $250.

I called Robert at the water department to give him the all clear. Unless you wanna go through that again, he sighed, open a faucet and let a pencil-lead stream of water run for the rest of the winter. It was mid-January. Surely he meant rest of the DAY. No. For the next six weeks, we let a pencil-lead stream of water run into the sink.

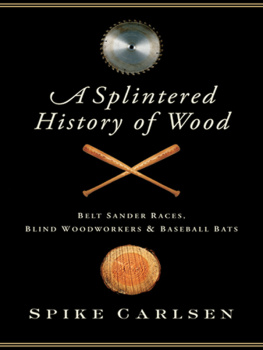

The endless trickle became a gnawing reminder of everything I didnt know. I really had no idea where our water came from. Or where it went. Or, for that matter, how my phone call to Robert had gotten to Robert. As I stared out the frost-etched window, I further realized I knew nothing about the concrete sidewalk leading to our door, the front lawn beneath the freshly fallen snow, the squirrels in the trees, the ancient walnut tree on the boulevard, the graffiti on the back of my neighbors garage... nothing. And these were just the things I could see through one dinky window. I realized Id read books about journeying across Antarctica, down the Amazon River, and up Mount Everest; Id written books about fifty-thousand-year-old wood buried in the bogs of New Zealand and the violin makers of Cremona, Italybut I knew nothing about the world right outside my front door.

A curious writer should do something about that.

When I launched into the research, I envisioned sitting at the Daily Grind, coffee steaming, fingers tapping, search engine searching. But the more I researched, the less I sat. I found myself hanging out with pigeon racers, traipsing through scorching power plants, stumbling through recycling facilities, and walking, stride-for-stride, with the Nordic Walking Queen. I meandered through Oakland Cemetery in Atlanta in search of the gravesite of the author of Gone with the Wind and through the streets of Carmel, California, to secure a copy of a permit for wearing high heels. It turns out that the story of things isnt so much about things as it is about peopletheir triumphs, failures, obsessions, and brilliance. Its about history, myths, and the future. Its about how things affect us and how we affect things. Those in academic and bureaucratic circles refer to these thingsthese pipes, wires, roads, signs, systemsby the soda-cracker-dry term infrastructure. I like to refer to them as the things that sustain us, as the awesome, essential, hidden and not-so-hidden world around, above, and below our feet.

What will you get out of this book? My guess is youll never look at a stoplight, squirrel, or manhole the same way. Just as knowing the rules, quirks, and history of, say, baseball or ballroom dancing makes watching these affairs more exciting, knowing the inner workings of the world outside your front door makes life more interesting. At a minimum, youll be a brilliant conversationalist at parties and while stuck in elevators. But theres more. The section on walking may help you live seven years longer. The section on trees may help you, your house, and your planet remain cooler and calmer. The interview with a founder of the zero-waste movement may radically change the size of your garbage can. The section on stoplights could save your, or someone elses, life. This awesome world isnt just a spectator sport. Its symbiotic; it influences us, and we influence it. We have some skin in this game.

Scientists have calculated the impact it would have if the entire populationall eight billion peoplegathered in one spot and jumped at the same time. That impact would shift the earths orbit the mere width of a hydrogen atom. But, if even a fraction of those people filled a pothole, installed a solar panel, or biked a little more, the impact would be real. Here youll discover a little more about whats worth jumping about.