Table of Contents

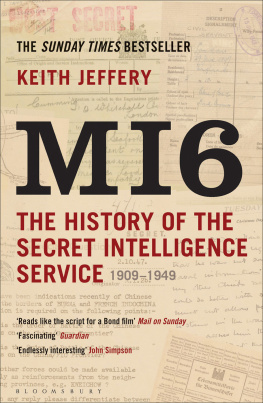

One of SISs founding documents: the letter of 10 August 1909 from Admiral Alexander Bethell (Director of Naval Intelligence) to Mansfield Cumming offering him something good, which turned out to be appointment as Chief of the new Secret Service.

Foreword

Keith Jefferys history of the Secret Intelligence Service 1909-1949 is a landmark in the history of the Service.

At the initiative of my predecessor, John Scarlett, SIS decided in the run up to our centenary to commission an independent and authoritative volume on the history of the Services first forty years. The aim was to increase public understanding of SIS by explaining our origin and role in a rigorous history, which would be accessible to the widest possible audience but would not damage national security. This is the first time we have given an academic from outside the Service such access to our archives. The Foreign Secretary of the day approved our plans.

Why focus on 1909-1949? Firstly, SISs first forty years cover a period of vital concern for the United Kingdom. Secondly, 1949 represents a watershed in our professional work with the move to Cold War targets and techniques. Thirdly and most importantly, full details of our history after 1949 are still too sensitive to place in the public domain. Up to 1949 Professor Jeffery has been free to tell a complete story and to put on the public record a well-informed picture of the intelligence contribution to a key period of twentieth-century history. During this time, SIS developed from a small, Europe-focused organisation into a worldwide professional Service ready to take an important role in the Cold War.

Throughout, we have been at pains to provide the necessary openness to enable the author to tell our history definitively. We take very seriously our obligations to protect our agents, our staff and all who assist us. Our policy on the non-release of records themselves, as opposed to information drawn from the archive, remains unchanged. A statement on this policy is outlined below.

Professor Jeffery has had unrestricted access to the Service archive covering the period of this work. He has made his own independent judgements as an experienced academic and scholar. In so doing he has given a detailed account of the challenges, successes and failures faced by the Service and its leadership in our first forty years.

Above all Professor Jefferys history gives a view of the men and women who, through hard work, dedicated service, character and courage, helped to establish and shape the Service in its difficult and demanding early days. I see these qualities displayed every day in the current Service as SIS staff continue to face danger in far-flung places to protect the United Kingdom and promote the national interest. I know my predecessors would be as proud as I am of the men and women of the Service today.

I am grateful to Keith Jeffery for accepting the appointment to write our history and to Queens University Belfast for releasing him for this task. It is a fascinating read. I commend it to you.

John Sawers,

Chief of the Secret Intelligence Service

SIS does not disclose the names of agents or of living members of staff and only in exceptional circumstances agrees to waive the anonymity of deceased staff. Exceptionally and in recognition of the Services aim in publishing the history it has been agreed that there is an overriding justification for making public, within the constraints of what the law permits, some information which ordinarily would be protected.

However, SISs policy has not restricted the occasional official release of some Service material - we have previously authorised a limited release of SIS information for other biographies of important intelligence figures.

An extensive clearance process with partner-departments and agencies has been implemented to ensure that the history does not compromise national security; is consistent with government policy on Neither confirm nor deny and does not damage the public interest. The author, therefore, does not identify by name any previously unnamed agents, only those named already in officially released documents, citations for wartime decorations, or previously approved publications. He also mentions a very small number of agents, who have already identified themselves. He names former staff only when judged essential for historical purposes and to satisfy the Services aim of informing public understanding of its origin and role.

Preface

The British Secret Intelligence Service - popularly known as MI6 - is the oldest continuously surviving foreign intelligence-gathering organisation in the world. It was founded in October 1909 as the Foreign Section of a new Secret Service Bureau, and over its first forty years grew from modest beginnings to a point in the early Cold War years when it had become a valued and permanent branch of the British state, established on a recognisably modern and professional basis. Although for most of this period SIS supervised British signals intelligence operations (most notably the Second World War triumphs at Bletchley Park over the German Enigma cyphers), it is primarily a human intelligence agency. While this history traces the organisational development of SIS and its relations with government - essential aspects for an understanding of how and why it operated - its story is essentially one of people, from the brilliant and idiosyncratic first Chief, Mansfield Cumming, and his two successors, Hugh Sinclair and Stewart Menzies, to the staff of the organisation - men and women who served it across the world - and, not least, to its agents, at the sharp end of the work. It is impossible to generalise about this eclectic and cosmopolitan mix of many nationalities. They included aristocrats and factory workers, society ladies and bureaucrats, patriots and traitors. Among them were individuals of high courage, many of whom (especially during the two world wars) paid with their lives for the vital and hazardous intelligence work they did.

SIS did not emerge from a complete intelligence vacuum. For centuries British governments had covertly gathered information on an ad hoc basis. In the seventeenth century successive English Secretaries of State assembled networks of spies when the country was particularly threatened, and from its establishment in 1782 the Foreign Office, using funding from what became known as the Secret Service Vote or the Secret Vote, annually approved by parliament, employed a variety of clandestine means to acquire information and warning about Britains enemies. But, after the turn of the twentieth century, with foreign rivals (Germany in particular) posing a growing challenge to national interests, British policy-makers began to look beyond these unsystematic and unco-ordinated methods. As the Foreign Office worried about the possibility of its diplomatic and consular representatives becoming caught up in (and inevitably embarrassed by) intelligence-gathering, the notion of establishing a dedicated, covert and, above all, deniable agency came to find favour.

The Secret Service Bureau, and the subsequent Secret Intelligence Service, remained publicly unacknowledged by the British government for over eighty years and was given a formal legal basis only by the Intelligence Services Act of 1994. The fact that a publicly available history of any sort has been commissioned, let alone one written by an independent professional historian, is an astounding development, bearing in mind the historic British legacy of secrecy and public silence about intelligence matters. It is also an extraordinary once-in-a-lifetime opportunity (and privilege) to be appointed to write this history, though I am well aware that the fact that I have been deemed suitable to undertake it may in some eyes precisely render me