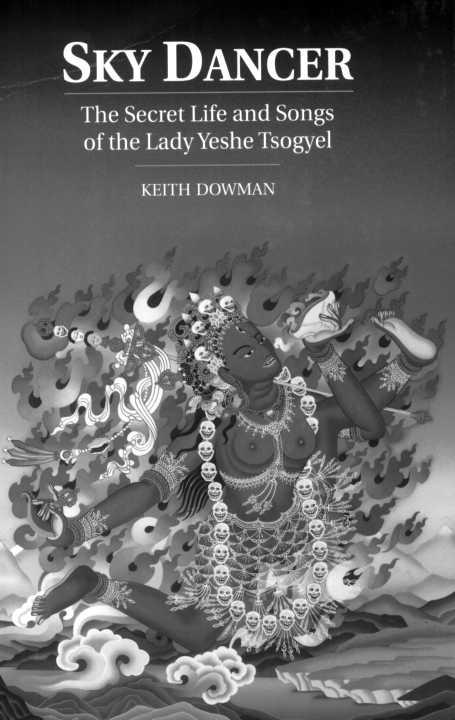

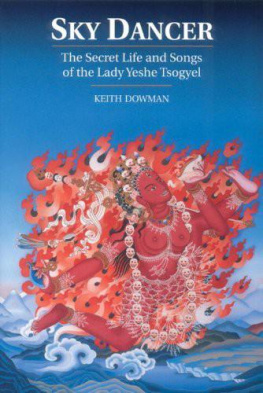

SKY DANCER

The Secret Life and Songs

of the Lady Yeshe Tsogyel

SKY DANCER

The Secret Life and Songs

of the Lady Yeshe Tsogyel

KEITH DOWMAN

Illustrated by Eva van Dam

HOMAGE TO THE GURU DAKINI!

This book is dedicated to the enlightenment of all sentient beings.

CONTENTS

ix

xii

THE SECRET LIFE AND SONGS OF THE LADY YESHE TSOGYEL

COMMENTARY

FOREWORD

TRINLEY NORBU RIMPOCHE

In the profound sutra system, the Dakini is called the Great Mother.Indescribable, unimaginable Perfection of Wisdom, Unborn, unobstructed essence of sky, She is sustained by self-awareness alone: I bow down before the Great Mother of the Victorious Ones, past, present and future.Thus it is written in the Great Paramita Sutra. In the precious tantric tradition, 'desireless, blissful wisdom is the essence of all desirable qualities, unobstructedly going and coming in endless space'. This wisdom is called 'the Sky Dancer', feminine wisdom, the Dakini.In the tantra system, the Three Jewels of the sutras are contained in the Three Roots - Guru, Deva, Dakini. One in essence, these three aspects are the three objects of refuge. Guru is the aspect that bestows blessing; Deva is the aspect that transmits siddhi; and Dakini is the aspect that accomplishes the Buddha's karma.In the tantra, countless objects of refuge appear spontaneously out of the one essential wisdom. Arising from wisdom as its reflection, all these forms are nirmanakaya. These forms can appear pure or impure according to the pattern of belief of the individual perceiving them.Sambhogakaya differs from nirmanakaya in that it is a pure, non-dual mandala that cannot be known by limited, individual perception. It can only be attained through pure, sublime, nondual being.Dharmakaya is the stainless space constantly pervading the sublime awareness of the sambhogakaya and the ordinary, individual perceptions of the nirmanakaya. In the dharmakaya's stainless space Yeshe Tsogyel is Kuntuzangmo, infinite and noble femininity itself. These names and qualities are no more than indications of the nature of the dharmakaya which can never be contained in, or identified by, concepts. Sambhogakaya is the glowing awareness of the dharmakaya, where the Five Buddhas and their Consorts appear as unobstructed luminous space-form. As the feminine aspect in the sambhogakaya, Yeshe Tsogyel is the Five Wisdom-Consorts.Yeshe Tsogyel is the nirmanakaya's multitude of forms; she appears as a Tara, Sarasvati, princess, ordinary girl, business woman, prostitute and so on. Also, she was born in Tibet as the daughter of the Prince of Kharchen, as her life story tells.Tibet's Great Guru, Padma Sambhava, possessed countless Dakinis. Appearing like gathering clouds, they accomplished his wisdom action. Among those countless Dakinis five were prominent: Monmo Tashi Khyeudren, Belwong Kalasiddhi, Belmo ~akya Devi and the two supreme consorts, Mandarava and Yeshe Tsogyel. 'Yeshe Tsogyel is the perfect vessel to contain the essence of the precious tantric teaching,' Padma Sambhava declared. And when Trisong Detsen, the King of Tibet, received initiation, he offered Yeshe Tsogyel, his Queen, together with the measureless universal mandala to the Great Guru. After that she accompanied him unswervingly, serving him continuously, giving her Body, Speech and Mind completely.The Guru gave Tsogyel the teaching for the suffering people of this coming degenerate kaliyuga. Tsogyel gathered all his speech carefully together, and after systematising it she hid it as secret treasure-troves. She hid it externally in different elements, and internally she hid it in the depths of mind. Each separate treasure included a prediction of the time of its discovery and the person who would find it. Thanks to Padma Sambhava and Yeshe Tsogyel we are using Yeshe Tsogyel's treasures today.Precious tantric teaching that has the quality of wisdom is naturally, unintentionally concealed - it lies beyond the ordinary, impure and concrete concepts of mind. Tantric teaching is also hidden intentionally to prevent misuse, the misuse that occurs if these precious treasures are used for selfish gain and fame, neglecting appropriate dedication to sentient beings. This creates obstacles to enlightenment. For one man to exploit the teaching is like one person using the electric current intended for an entire city to light his own small bulb - the one bulb is destroyed and perhaps others on the circuit are damaged.Secrecy is important, but it is especially important for Dzokchen, the Great Perfection teaching, which uses intangible luminous elements to transform the tangible body into a magic rainbow body.Those who read the biography of the supreme tantric master, Padma Sambhava, and his Consort, Yeshe Tsogyel, have the chance to identify with them, and those who cultivate the inner wisdom Dakini, the root Dakini, progress towards becoming the supreme Sky Dancer, incomprehensible feminine wisdom, the lover without motive.Keith Dowman has translated The Life of Yeshe Tsogyel for the benefit of all sentient beings. For this I remain thankful.May this wonderful history bring the turbulent river of frustrated and neurotic men and women to the attainment of the Ocean of Enriching Wisdom that is Stillness and Bliss.Trinley NorbuMahankalKathmanduNepal

TRANSLATOR'S

INTRODUCTION

For twenty-five hundred years the Buddhist's goal has not altered - the perfection of man as the Buddha. However, down the centuries, as the faith expanded to include all sections of Indian society, besides other cultures, different schools redefined the nature of the Buddha, and new methods, or vehicles, were developed to traverse the path to Buddhahood. These vehicles differed as much as a tortoise from a hare or a deer from a lion. In the golden age of ~akyamuni Buddha an ascetic path of exalted yet simple self-discipline led through many lifetimes to a nirvana of cessation. Later the lay devotee entered the path to strive for the compassionate Bodhisattva ideal, perfecting personal and social virtue, but postponing his final nirvana until all beings could accompany him. Then in the mature efflorescence of Indian spiritual genius Buddhism assimilated the cult of the Mother Goddess; in the Buddhist Tantra mysticism and magic, ritual and incantation, characterise the path of the yogin who does not abandon the senses and emotions but uses them as the means to attain Buddhahood during his lifetime. The Bodhisattvas acquired consorts, pairs of deities represented every conceivable mode of being; and the mystery of Buddhahood was expressed in terms of the union of sexual duality.It was tantric Buddhism that the Second Buddha, Padma Sambhava, who we shall call Guru Perna, first taught in eighthcentury Tibet. The Guru's favourite consort was a Tibetan princess given to him by the Emperor Trisong Detsen. Her name was Yeshe Tsogyel, and in the cult that grew up around her and her Guru, she became the Guru Dakini, the Sky Dancer, the embodiment of the female Buddha. The name of the school that practises Guru Pema and Yeshe Tsogyel's instruction on their path of personal evolution is called the Old School, the Nyingmapa (rNying-ma-pa), and in the Old School's innumerable legendary biographies of Guru Pema is contained much of Yeshe Tsogyel's life story. But it was not until the eighteenth century that an inspired tantric yogin called Taksham Nuden Dorje revealed a separate biography of Tsogyel, a work that was to become renowned as a masterpiece of this genre of Tibetan literature.The Secret Life and Songs of the Tibetan Lady Yeshe Tsogyel (Bodkyi jo-mo ye-shes mtsho-rgyal-gyi mdzad-tshul rnam-par-thar-pa gabpa mngon-byung rgyud-mangs dri-za'i glu-'phreng) is styled 'secret' (gab-pa) because its essential meaning lies on the 'secret' level of tantric analysis. The work reveals Tsogyel's total being as a sphere of non-duality in which Guru and Dakini in union inhabit a pure-land of gods and goddesses; it describes the secret empowerments and vows which accompany initiation into the tantric mysteries; and it elucidates the precepts of the Inner Tantra (anuttarayoga-tantra), practical precepts as relevant now as for Tsogyel's own disciples. But in order to give narrative flow to the work, Taksham wove the secret life of Tsogyel into the pageantry of great events that were revolutionising Tibet, events in which Tsogyel herself played a significant role. Thus in recounting the public life of Tsogyel, Taksham relates the history of the Emperor Trisong Detsen's reign, and although his account accords with the legends of the early revealed histories, the inclusion of certain episodes and details makes this a valuable source for historians.To express his vision of the secret life of Yeshe Tsogyel Taksham employed the conventional literary devices of Tibetan tantric biography (rnam-thar): mandalas, metaphysics, tantric symbology, twilight language and poetry. With these tools he describes an ideal path of practice that the tantric neophyte can emulate. In her final instruction to her disciples Tsogyel refers them to her biography for direction on the path of Tantra. Although the exigencies of the English language tend to reduce the divine Dakini to human size, it is still evident that a Buddha's reality is being described from the moment of the Dakini's birth; in the Tibetan text honorific pronominals and verb-forms and the highly specific epithets of the heroine constantly evoke a supra-human reality. Thus the reader will be disappointed if he is looking for humanistic biography. But as an introduction to the Tibetan Tantra this biography is second to none; only The Life of Milarepa can compare with it in its power to evoke the spirit of the Tantra and reflect the nature of the path.Although this secret biography is aimed primarily at practitioners of the Inner Tantra, on an exoteric level it also presents Tsogyel as a subject for deification. Her story provides all the ingredients necessary for devotees of the Outer Tantra (kriyay- oga-tantra in particular) to worship her as a goddess. A miraculous birth, flight from persecution and to self-exile, untold ascetic sacrifice to a selfless end, miraculous Christ-like deeds such as resurrecting the dead, healing the sick, feeding the multitude and making a gift of her body to the needy, a profound, ideal relationship with her Lama, and finally the attainment of Buddhahood in a body of light: such material stirs the religious spirit and induces a mind so disposed to take refuge in a goddess who can assuage all life's suffering and offer all life's joys. But Tsogyel warns her disciples on the path of the Inner Tantra against conceiving her as an external entity, a 'person' separate from the perceiver; their aim should not be to propitiate a god or goddess 'out there' capable of bestowing boons upon his or her devotees, whether such favours are the man or woman of their choice or the power (siddhi) of flying in the sky. Tsogyel asks these disciples to take her as their consort, either incarnate or metaphysical, so that she can give them the pure pleasure of gnostic awareness; and attaining the ultimate power, every man and woman is a Guru and Dakini - a Sky Dancer.A fact that further enhances the work's extraordinary reputation is that The Life and Songs of Yeshe Tsogyel is one of the few texts in the immense Tibetan scriptural literature that treats woman on the tantric path, or indeed, represents woman at all. Perhaps only a dozen women have risen to eminence in Tibetan Buddhism, and of these many were influenced by Tsogyel's crucial metaphysical role in the Old School tradition. The wonderful Machik Labdron, for example, the Dakini Guru of the lineage of 'Severance' (gcod), was an incarnation of Tsogyel. But although The Life is a veritable treasury of precepts and advice for yoginis on the path, most of the theory and practice is equally relevant to male practitioners; apart from the initiation rites, the third initiation yogas described in the text, and certain other special cases, the instruction is applicable to all.Taksham himself was the kind of man who breathes new life into the traditional rites and doctrines that lineages unthinkingly transmit from generation to generation. Extracting the essential message such an adept can reformulate the teaching and express it in a manner that conveys his existential realisation. Taksham was no doctrinaire scholar; he was in fact seen by his contemporaries as a divine madman (zhig-po), a wrathful, though compassionate, crazy saint (dpa'-bo). In The Life, though he reveals the secrets of Tantra discreetly, endangering neither Guru nor disciple, his existential analysis cuts close to the bone, his vision is always uncompromising and fearlessly honest, and his humour is clever and sharp. His colophon to The Life is written in an obscure allusive style as if written by a man halfcrazed by a terrible environment and the woes of existence.Taksham was born in one of Kham's valleys (Lhorong Kham) in S.E. Tibet, 'in a land of impassable narrow defiles', a land of ravines cut by the great rivers of Kham - the Mekhong, Irrawaddy and Salween. Khetsun Sangpo in his Biographical Dictionary (Vol. III, p. 804) quotes Pawo Tsuklak's History of the Dharma where an unnamed Thang-yig is cited: 'a yogin called Nuden Dorje will take out the Kham caches of Guru Rimpoche's treasures.' He was prolific in discovery, revealing cycles of treasure-texts for each of the 'three roots' (Guru, Deva and Dakini) and the Dharma Protectors, and much more. His principal cycle concerned a form of Guru Pema called Lama Yishi Norbu (bLa-ma yid-bzhin nor-bu), and the Yidam Gongdu (Yi-dam dgongs-'dus), a part of Tsogyel's sadhana (her personal endeavour), was the chief means of accomplishing this form of the Guru. He also discovered images, stupas and mantras. He held the lineage of revealed teaching (gter-chos) of the great Knowledge Holder Dudul Dorje, like Longsel Nyingpo, Yolmo Tulku Tenzin Norbu and Katok Tsewong Norbu. Further, he had a strong karmic bond with the Master Choje Lingpa, and it appears that Choje, either reincarnate, or appearing in vision, was his Guru. But it was as a reincarnation of Atsara Sale, Gyelwa Jangchub, who was Tsogyel's consort, that he gained access to the secrets of Tsogyel's Life. Taksham's colophon recounts that he copied out the text of The Life 'on a black day, the 29th' in a forest hermitage, but no month or year is mentioned. In fact we know only that he lived in the eighteenth century. His name means Tiger-skin Dynamic Vajra; and he is also known as Samten Lingpa (bSam-gtan-gling-pa).The Life is a revealed scripture, a terma. The nature of termas and the profound doctrine underlying the tradition of revealed texts is discussed in the commentary under the head 'The Nyingma Lineages'. Here suffice it to say that legend records that Guru Perna and Tsogyel hid many treasures of different kinds in innumerable caches throughout Tibet, treasures that were to be revealed by tertons (treasure finders) when the moment was ripe. Further, some treasures were hidden internally, in inner space; this category of terma is called mindtreasure (dgongs-gter) and may be considered as direct revelation of Guru and Dakini. The original colophon of The Life informs us that Gyelwa Jangchub and Namkhai Nyingpo of Lhodrak wrote down Tsogyel's memoirs verbatim on yellow parchment, concealing the completed text in Lhorong in Kham. In the catalogue of prophets (lung-byang) in the text, 'a dpa'-bo of Lhorong in Kham called Dorje' is mentioned amongst the nine possible tertons who might discover the text. Taksham's colophon tells how he received the text from its protector, Lord of the Black Water (Chu-bdag-nag-po), who in the text's prefatory Protection is called Black Nyong-kha (sNyong-kha?) Blazing Lord of Devils (bDud-rje 'bar-ba). Gyelwa Jangchub's colophon informs us that Lord of the Black Water, Thousand Beings (?) (sTong-rgyug), was instructed to deliver it into the hand of the terton. Although an actual manuscript treasure is indicated here, a study of the manuscript reveals significant variations in style, conflicting historical facts, material relevant to Taksham's era, prophecy up to the seventeenth century, etc. Undoubtedly Taksham had access to ancient material, e.g. the Bon worship of the king, and, perhaps, a biography of Tsogyel written by Gyelwa Jangchub, but the text translated herein was written by Taksham Nuden Dorje. However, since The Life is an inspired work that can be said to have its spiritual genesis in the milieu of 'the Guru and Dakini s union in lotus light', certainly it can be classified as a 'mind-treasure'. For the yogin such discussion of the authenticity and category of The Life is irrelevant; either the power of the Guru's Word illuminates every page, or it does not, and the efficacy of its precepts are proven experientially.In various passages in the text relating Tsogyel's own experiences the first person singular is employed, and some historical episodes are described from Tsogyel's point of view. Since such passages accord with the colophon's claim that Tsogyel dictated the text herself, and because the use of the first person is effective in creating a more intimate relationship between Tsogyel and the reader as well as maintaining continuity of style, I have taken poetic licence to use the first person throughout. The introductory and concluding sentences of each chapter have been excluded from this.In translating The Life my principal concern has been to convey the precise meaning and feeling-tone of the original in fluent English, rather than to reproduce the peculiarities of the Tibetan style and diction. In order to achieve this aim occasionally I have employed paraphrase. I have solved part of the problem of translating technical tantric terminology by the use of 'symbol words'. Thus words with an initial capital letter contain deeper significance than their face value implies; Awareness (jnana, ye-shes), Knowledge (rig-pa), Emptiness (stong-pa-nyid), and Body, Speech and Mind (sku, gsung, thugs) are attributes or qualities of the Buddha. Where I have used an adjective to describe the nature of these attributes as in 'gnostic awareness' or 'non-referential awareness', the qualifier limits an essentially inexpressible idea.Although I tried to avoid all foreign words and phrases, I failed. The words mantra, mandala and nirvana are already included in the Oxford Dictionary, albeit with non-technical definitions, and surely mudra (gesture or posture), samadhi (nirvanic state of mind), siddhi (success or power), samaya (vow or union) and of course Dakini (female Buddha-Guru and goddess) will soon join them. Further, there is no meaningful succinct equivalent for the Tibetan word Yidam (personal deity) or terma (literally 'treasure' or 'cache'). Some English poets would translate 'terma' as 'poetry', 'terton' (treasure-finder) as 'poet' and 'Dakini' as 'the Muse'; some would say that the treasures Tsogyel hid in England are English poetry. Perhaps the most problematic terms for translation are the names of the Buddha's three modes of being (trikaya). Rather than employ the Sanskrit terms throughout, I have used admittedly inadequate interpretive translations: 'absolute, or essential, empty being' for dharmakaya, 'being of consummate visionary enjoyment', or 'instructive visonary being', for sambhogakaya, and 'apparitional being' for nirmanakdya. The Tibetan word gyud (rgyud, Sanskrit: tantra), has many meanings. In this translation 'Tantra' denotes the practical system of yoga and the continuum of enlightened being that results from its practice, while tantra, or tantras, denotes a single text, or a corpus of scripture, that treats tantric yoga. Another problem in the translation of The Life has been to maintain the ambiguity of twilight language (sandhyabhasa). For instance, when sexual union and mystical union are implied by the same words the translation must not stress one level at the expense of the other; it must contain the same potential for multi-levelled interpretation as the original. Sometimes this proved impossible.In the text I have rendered Tibetan names in simple phonetic forms approximating the Lhasa dialect, as transliteration is misleading and tongue-tying for the reader with no knowledge of Tibetan. The index gives the transliterated forms. In general, in the notes and commentary I have retained the phonetic forms of proper names used in the text while transliterating other names and technical terms. Another cause of apology to scholars is the inconsistent use of Tibetan and Sanskrit for both names and technical terms. Believing that most students of Tibetan dharma acquire a mixed vocabulary I have used whatever form I thought most familiar, or most useful, to them. In the notes I have given the Tibetan equivalents except when the Sanskrit form should be familiar, although sometimes I have given both Tibetan and Sanskrit. Consistency has, therefore, received short shrift, and although some readers will be offended I hope to have helped the student of dharma.This translation and commentary have been several years in preparation. Authorisation to read, study and publish the translation of The Life was given by His Holiness Dunjom Rimpoche, the principal hierarch of the Nyingma School; the Tibetan wood-blocks of the text were printed at Dunjom Rimpoche's Zangdokperi Monastery in Kalimpong. The first stage of the translation was to listen to a Nyingma lay scholar, Se Kusho Chomphel Namgyel, rendering the text into English. Then studying the passages on initiation, meditation instruction and the secret precepts in Chapter 8, etc., I was assisted by Khetsun Sangpo, probably the most eminent Nyingma scholar alive. But exegesis of the Dzokchen philosophical view, from which standpoint the text is written, and a detailed commentary upon the difficult passages of tantric precept, I received from Namkhai Norbu, an unorthodox Dzokchenpa with a profound experiential knowledge of the Inner Tantra. I felt his transmission (lung) of a vision of the Sky Dancer, the Dakini, to be an informal initiation into the yogini-tantra. Namkhai Norbu, a tulku of Azom Drukpa, is professor of Tibetan Studies at Naples University, Italy; he also teaches practical Dzokchen meditation as a self-contained system of yoga in various European and American cities.When the translation was finished it became evident that the general reader would require commentary to provide metaphysical and historical background to this popular, but abstruse, Tibetan classic. A short foreword couched in the traditional imagery of the Dakini in a metaphysical framework has been written by Trinley Norbu Rimpoche, one of the few remaining Tibetan recipients of Dzokchen precepts possessing both theoretical and experiential understanding who can express Dzokchen for a western audience. The text was annotated with the purpose of elucidating tantric terminology and practices. Concepts and practices and also historical allusions in the text that required greater amplification I have elucidated in the commentarial essays in the second half of the book, although I omitted references to the appropriate page to keep annotation to a minimum. In so short a space it was impossible to treat the tradition comprehensively and no doubt important aspects were overlooked. 'The Path of the Inner Tantra' is a personal view based upon my own experience, observation and the oral transmission. The first part of 'Woman and the Dakini' is a tentative exploration of the means of expression of a crucial aspect of Tantra and a verbal attempt to resolve paradoxes that can only be fully resolved experientially. 'The Nyingma Lineages' deals with Dzokchen's origins, the nature of kama (bka'-ma) and terma (gter-ma), the relationship between Bon and the Nyingmapa and other fascinating topics relating to the genesis of the Old School. It may increase appreciation of the text if these essays are read first.In general the historical events described in The Life agree with the legends related in the early termas; but several episodes are expanded, particularly the great debate with the Bon, which is not described in other histories. My primary sources for the 'Historical Background' and 'The Nyingma Lineages' (I have reduced references to them to a minimum) are Orgyen Lingpa's Padma bka'-thang Shel-brag-ma, Nyima Wozer's Guru rnam-thar Zangs-gling-ma, the Genealogy of Kings (rGyal-rabs gsal-ba'i-me- long), The Red Annals (sDeb-ther dmar-po), The Blue Annals (sDeb- ther sngon-po) of 'Gos Lotsawa, The Ladakhi Chronicles (La-dvags rgyal-rabs), Buton's History of the Dharma and Dunjom Rimpoche's History of the Dharma (Chos-'byung). I relied on Professor Tucci's works (Tibetan Painted Scrolls and Minor Buddhist Texts), and Hugh Richardson's articles, for knowledge of other early sources such as the Tun Huang chronicles and The Samye Chronicles (sBa-shad). Eva Dargyay's Rise of Esoteric Buddhism in Tibet must also be mentioned. I have accepted much of the Nyingma legend as historical fact, but with discrimination, while rejecting the revisionists who follow Sumpa Khempo, a biased adversary of the Old School. One major history remains ignored; Longchen Rabjampa's History of the Dharma (Chos-'byung) must one day be accorded its rightful place as the most reliable and authoritative text of the Chos-'byung genre, superseding Buton's later work.It remains for me to thank all those who have helped me in the creation of this book: my Tibetan teachers, His Holiness Dunjom Rimpoche, Khetsun Sangpo, Namkhai Norbu Rimpoche, Trinley Norbu Rimpoche and Chomphel Namgyel, I credit with whatever here is true and consistent with Dzokchen doctrine, and for the understanding they have given me I am infinitely grateful. To Leonard van der Kuijp and Tadeuz Skorupski my thanks for reading the commentary and offering much useful advice. I am indebted to many others who have helped me in many ways during the course of the work, particularly to my wife Meryl for unfailing support and to Mimi Church, Cass Bardwell, Bill Gye and Vikki Floyd for their time and energy. Lastly, my thanks to Eva van Dam for the fine illustrations done out of pure devotion.Keith Dowman, Kathmandu, Nepal.

Next page