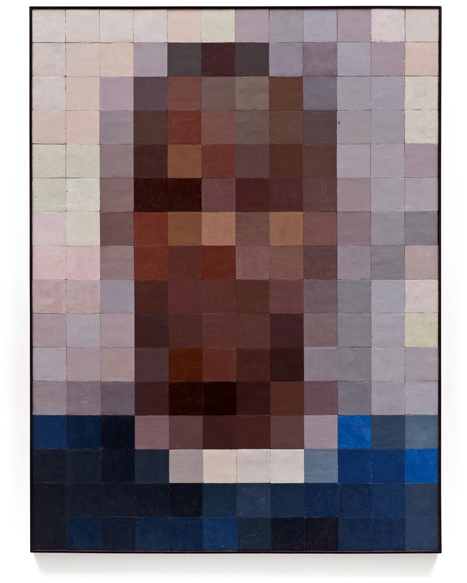

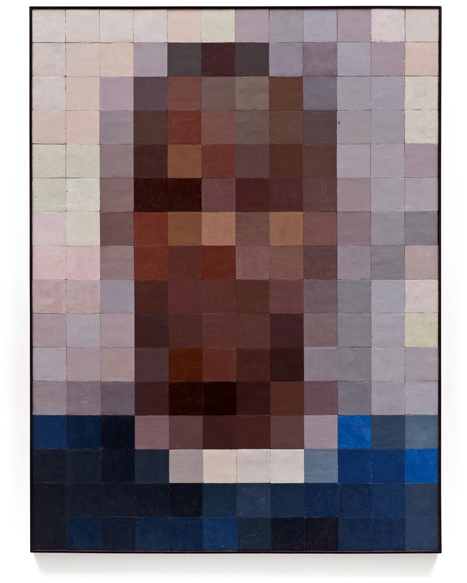

Channel 11 by Kori Newkirk. 1999. Encaustic on wood panel. Collection of the Santa Barbara Museum of Art. Gift of Barry Sloane.

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Contents

To great teachers:

Dicksie Tamanaha, Kathleen Dudden Rowlands, William Y.S. Lee, Gary Delgado, Don Nakanishi, Roberta Uno & Kate Hobbs

To the memory of

Ronald Takaki and Morrie Turner

The gods were fighting. And the gods were fighting because the world was very boring, with only two colors to paint it.

A folktale from Chiapas retold by Subcomandante Marcos, La Historia de los Colores

Photo by B+ from the series Is A Record Like A Wheel

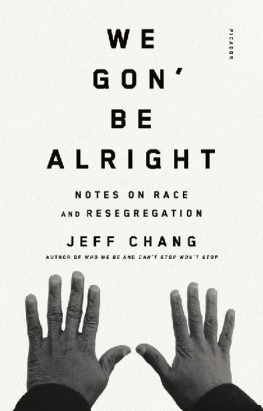

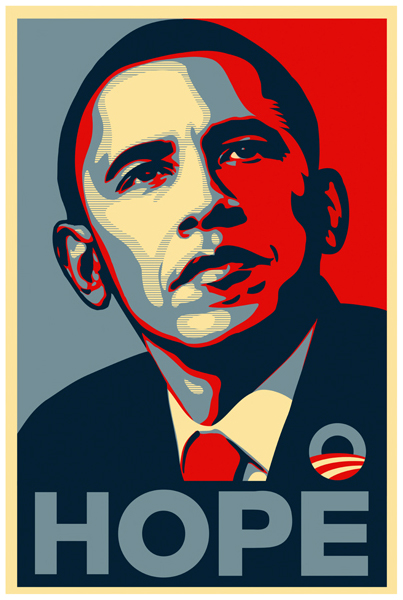

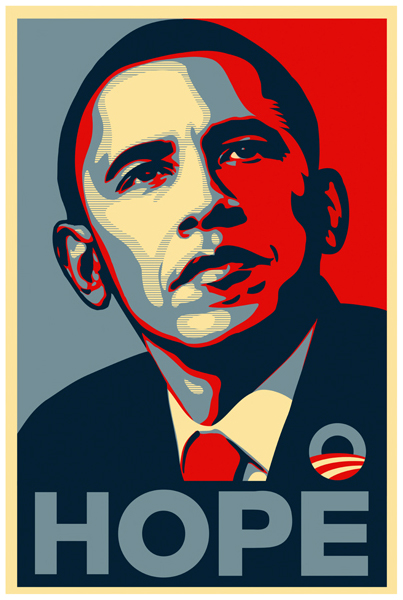

Obama HOPE poster by Shepard Fairey. 2008.

INTRODUCTION

SEEING AMERICA

I

For most of 2008, the most arresting image in America was a screen print by the street artist Shepard Fairey that appeared on posters, stickers, and clothing from sea to shining sea. The image was of a Black and white man rendered in red, white, and blue. The man was named Barack Obama and the four-letter word below his image was HOPE.

Obama was, of course, the presidential candidate who had come from the far geographic and cultural edge of the United States, its Pacific borderland in Hawaii, to secure the Democratic Party nomination. He had run on a platform of mending a divided country. In a speech he gave in March that he called A More Perfect Union, he offered his own biracial heritagethe unity of Black and white histories in his own bodyas a symbol of empathy and reconciliation.

That address, now popularly known as the race speech, was in some ways as historic as Martin Luther King Jr.s I Have a Dream speech, delivered at the Lincoln Memorial almost forty-five years earlier. The complexities of race in this country that weve never really worked through, Obama said, remained a part of our union that we have yet to perfect. If Americans could move forward on race, he seemed to say, they could move forward on anything.

By then demographers had become accustomed to naming each new cohort of youths the most diverse generation the nation had ever seen. One in three Americans was of color. They formed the majority in a third of the countrys most populous counties, and in forerunner states like California, Texas, New Mexico, and Hawaii.

In 2000, voters of color made up only 19 percent of the electorate, but in 2004, more than half of all new voters between the ages of eighteen and twenty-nine were Black or Latino. In 2008, youth and voters of color turned out in record numbers, forming the foundation of a new electorate that put Obama into office. By 2012, more than a quarter of voters were of color. It seemed apparent that an emergent majority had spoken once again at the polls, loudly.

Experts had begun projecting that sometime, perhaps as early as 2042, the United States would become majority-minority. The notion seemed stranger with each new censusif no race was a majority, then wouldnt each be a minority? And just what would it mean for the nation?

The country in which Barack Obama could take the oath of office on the inaugural platform at the West Front of the Capitol building was most certainly not the same as the one in which Martin Luther King Jr. addressed the nation from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. For that to have occurred, America needed to understand itself differently than it had for most of its first two centuries, which had been marked by formal racial segregation. Even after the civil rights movement enabled dramatic and sweeping legislative and judicial changes, those changes could take Americans only part of the way toward desegregation. Laws could not tell people how to see each other, how to be with each other, how to live together. They would have to find a new way of seeing America.

The United States had been historically defined by whiteness, drawn in grays, shades of white and black. But in Faireys famous print Obama had been colorized, to coin a phrase, just as the country to and for which he had become a symbol had been colorized. Colorization describes the massive shifts that began taking place as the civil rights movement began to ebb. These shifts were demographic and would have political implications. But the most profound changes have been cultural.

This is where we begin: How has the national culture changed over the past half-century that we could elect a Black president? And, just as important, how has it not changed?

To begin to answer these questions we must address that most complicated of American words, another four-letter word: race.

II

We can all agree that race is not a question of biology. Instead it is a question of culture and it begins as a visual problem, one of vision and visuality. Race happens in the gap between appearance and the perception of difference. It is about what we see and what we think we see and what we think about when we see. In that sense, its bigger than personal affinities, preferences, tastes, and bonds.

Race has driven centuries of civil and cultural schisms and periodically brought the nation to the brink of dissolution. In 1952, Ralph Ellison encapsulated the central problem of race and American visuality. I am invisible, understand, simply because people refuse to see me, his protagonist remarked in the famous prologue to Invisible Man. When they approach me they see only my surroundings, themselves, or figments of their imaginationindeed, everything and anything except me.

Difference is human, and noticing difference is human. For us, it begins as babies, from our very earliest days of perception. But of course Ellison was pointing out that Americas race problem came from something deeper. For whites, historically, skin tone and physiognomy signaled not only difference, but notions of superiority and inferiority. This was the way racial power worked. It went further than merely perceiving difference. It sorted difference into vast systems of freedom and slavery, commitment and neglect, investment and abandonment, mobility and containment.

Then it drew a veil over these systems. It pretended not to have even seen difference in the first place. Racism, in other words, was supported by a specific kind of refusal, a denial of empathy, a mass-willed blindness. In this context, the Others true self might always remain unseen. The Other might always bear the burden of representation.

The musician and intellectual Vijay Iyer has compared seeing to listening. When we feel empathy for another person, he reminds us, our brains mirror neurons fire. We understand anothers pain or joy at the root level of our being. Art, music, and literature can move us in the same way.

But psychologists and neuroscientists also warn that visual racialized difference gets in the way of empathy. Between a childs curiosity about difference and an adults perception of difference, something has changed. We have learned to be compassionate or fearful before what we see.