BY THE SAME AUTHOR

Pendulum of War

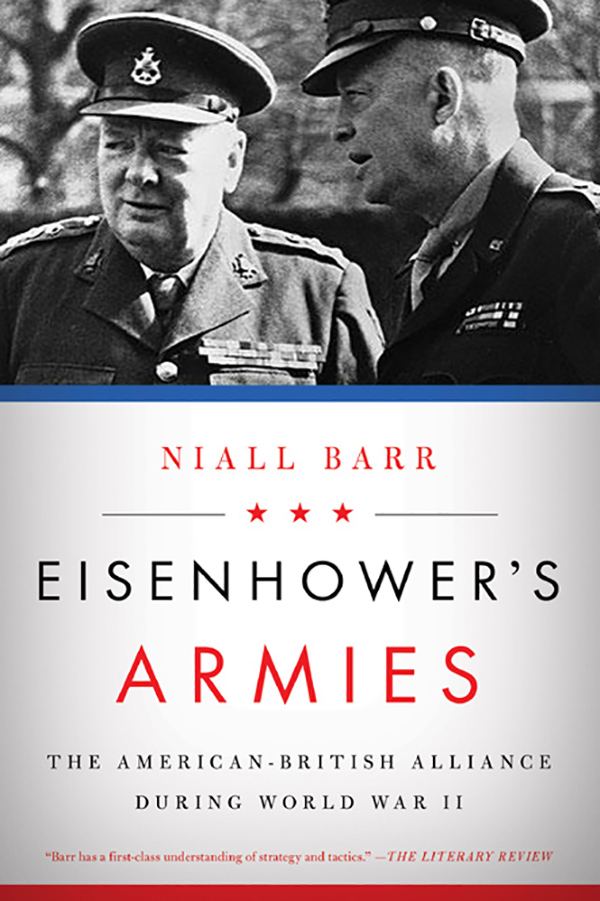

EISENHOWERS

ARMIES

THE AMERICANBRITISH ALLIANCE

DURING WORLD WAR II

NIALL BARR

PEGASUS BOOKS

NEW YORK LONDON

EISENHOWERS ARMIES

Pegasus Books LLC

80 Broad Street, 5th Floor

New York, NY 10004

Copyright 2015 by Niall Barr

First Pegasus Books hardcover edition December 2015

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in whole or in part without

written permission from the publisher, except by reviewers who may quote brief excerpts in

connection with a review in a newspaper, magazine, or electronic publication; nor may any

part of this book be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form

or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or other,

without written permission from the publisher.

ISBN: 978-1-60598-816-0

ISBN: 978-1-60598-817-7 (e-book)

Distributed by W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

In February 1755, two British ships made landfall off the Hampton Roads, Virginia. On board were the first regular British troops to arrive in the American colonies for over fifty years. These British soldiers, numbering more than 1,000 men, formed the core of the command of General Edward Braddock, newly created commander-in-chief of the British colonies in North America. Braddock had been sent to check the expansion of the French, who had begun to encroach on British possessions. The French strategy was only now becoming clear to the American colonists: they planned to stake their claim to the enormous hinterland beyond the British colonies on the American seaboard. By building a chain of forts, the French hoped to link their possessions in Canada with their settlements in Louisiana. If they were successful, British America might eventually be confined to the coast.

Two years earlier, in late 1753, Lieutenant Governor Dinwiddie of Virginia had sent a young surveyor, Major George Washington, to remonstrate with the French in the critical area of the Ohio valley. After a series of exchanges, the French had made it clear that the land was now theirs, and London had charged the colonies to drive them out by force of arms.mission attempting to contact Washington. Washington prepared a small fort, Fort Necessity, at Great Meadows to await the French reaction.

On 3 July, the French and their Indian allies attacked. After a day of fighting, with the Virginians hemmed in around Fort Necessity, and having suffered 30 dead and 70 wounded, Washington sued for terms. The next morning, he and his men were allowed to march out of the fort, but he had been forced to sign terms that amounted to a confession that his killing of Jumonville had been an assassination rather than an act of war. Far from dealing with the French threat to the Ohio valley, Washingtons expedition had actually increased the French influence with the Indian tribes in the area. The Fourth of July would remain Washingtons least favourite date in the calendar. These minor incidents in the backwoods of Pennsylvania precipitated outright war between Britain and France, which soon became a global conflict, with both powers competing for influence and territory in Europe, America and India. With the failure of the American colonies to deal with their security difficulties themselves, it was entirely logical that the British government decided to send regular troops to North America.

When General Braddock arrived with his troops in February 1755, he was received enthusiastically by the colonial authorities. Here was a clear sign that the British government was taking colonial problems seriously. Braddock had an enormous task before him. He proposed a four-pronged assault on the ring of French forts that hemmed in British North America. He himself would take the two regiments of British regulars and march on Fort Duquesne at the Ohio Forks; meanwhile, further freshly raised colonial regiments would attack Niagara and Crown Point on the borders of French Canada, while a New England force would conquer Acadia in Newfoundland. However, Braddocks timetable was soon derailed. The colonial authorities could not or would not supply him with sufficient men and materiel for his long march. It was not until 10 May that he felt able to begin his campaign, with his regulars now augmented with nine companies of the newly raised Virginia Regiment. Braddock complained of the Virginia Regiment that their slothful and languid disposition George Washington, on the other hand, impressed Braddock, and although he could not secure a regular commission for the ambitious young man, he did take him along as his aide-de-camp and adviser on the expedition.

The advance of the expedition towards Fort Duquesne was painfully slow: 300 axemen had to cut a road through the virgin forest to enable the supply wagons and guns to traverse the steep ridges and valleys of the Allegheny mountains. Eventually, on 9 July 1755, after much toil, Braddock knew that one more march would put him within sight of his goal. When the army crossed the Monongahela River for the second time, the regimental standards were unfurled and the bands played in a deliberate attempt to overawe any watching French. Thomas Walker, a British soldier, claimed that A finer sight could not have been beheld, the shining barrels of the muskets, the excellent order of the men, the cleanliness of their appearance, the joy depicted on every face at being so near Fort Duquesne, the highest object of their wishes. The music re-echoed through the mountains. Washington later claimed that it was the finest military sight that he ever saw. Braddock and his officers had been apprehensive of a French attack, but they had now marched so close to the fort that they imagined there would be little if any resistance.

While the Indians fired from the cover of the dense woodland, the British wheeled into line, shoulder to shoulder, to deliver the controlled volleys of musketry that their drill sergeants had taught them were the key to victory on the battlefield. Unable to see their enemy, the British troops fired volley after volley into the trees with little effect, although one of their first rounds did kill Beaujeu. Indeed, it appears that many of the French troops melted away soon after the action began; it was the Indians, using their traditional tactics of rushing forward and firing from the cover of the trees, who continued the fight.

Eventually, with their ranks thinned by the sharp sniping of the invisible Indians, the remaining British troops broke and ran back just as Braddock appeared bringing up the main body of the British battalions. Very soon the entire force was clumped together in a confused mass, firing in all directions. Braddock shouted and swore at his men to re-form the line as the sniping continued. Terrified by the war whoops of their invisible enemies, the regulars even fired upon the Virginian volunteers. When some of the Virginians sought cover behind the trees to fight Indian style, Braddock forced them back into line.

After three hours of this unequal fight, Braddock, who had four horses shot under him, ordered a retreat. Soon after, he was shot off his horse and the British troops began to run. Washington said that when we endeavoured to rally them, it was with as much success as if we had attempted to stop the wild bears of the mountains.

The shocking reality of Braddocks defeat brought serious consequences for the American colonies. Britain had attempted but failed to protect them. Their frontiers were now open to continued French expansion and the depredations of Indian war parties. Angry colonists sought to apportion blame for the disaster, and the British officers, attempting to exonerate themselves, blamed their own men. Robert Orme, one of Braddocks aides-de-camp, later stated that when the General found it impossible to persuade them to advance, and no enemy appeared in view; and nevertheless a vast number of officers were killed, by exposing themselves before the men; he endeavoured to retreat them in good order, but the panic was so great that he could not succeed.

Next page

![Russell - Leaping The Atlantic Wall - Army Air Forces Campaigns In Western Europe, 1942-1945 [Illustrated Edition]](/uploads/posts/book/94591/thumbs/russell-leaping-the-atlantic-wall-army-air.jpg)