THE CHINESE MACHIAVELLI

The Chinese Machiavelli

3000 Years of Chinese Statecraft

Dennis Bloodworth

Ching Ping Bloodworth

With a new preface by Peter Li

Originally published in 1976 by Farrar, Straus and Giroux

Published 2004 by Transaction Publishers

Published 2017 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

New material this edition copyright 2004 by Taylor & Francis.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Catalog Number: 2003059346

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Bloodworth, Dennis.

The Chinese Machiavelli: 3000 years of Chinese statecraft/Dennis Blood

worth & Ching Ping Bloodworth, with a new preface by Peter Li.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-7658-0568-5

I.ChinaPolitics and government. I. Title: 3000 years of Chinese state

craft. II. Bloodworth, Ching Ping. III. Title.

DS740.B52 2004

320.951dc22 2003059346

ISBN 13: 978-0-7658-0568-3 (pbk)

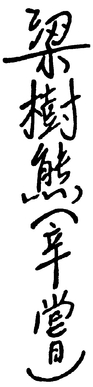

IN MEMORY OF

Liang Shu-hsiung, known as Liang Hsin-ch'ang

(1878-1931)

Contents

Guide

Maps

The Chinese Machiavelli is an unconventional book in that it examines Chinese history and politics from the less popular but more realistic Legalist perspective as opposed to the more conventional Confucian point of view. Most likely, this book will not make the reading lists of courses on Chinese history and politics (perhaps it should), but it is a book well worth reading and savoring. It teaches many valuable lessons on Chinese history that cannot be found in standard texts. The book reveals to us the "underbelly of the beast" as it were.

It is true that China became a Confucian state some time between the second and first century before the Common Era during the reign of Emperor Wu (141-86 BCE) of the Han Dynasty. Imperial Confucianism became the state ideology and the popular tenants of Confucianismsuch as the Five Cardinal Relationships, which taught the hierarchical relations between subject-ruler, father-son, husband-wife, elder brother-younger brother, friend-friendbecame some of the fundamental guiding forces in society. But beneath this veneer of Confucianism, which foregrounded the virtues of humanity, benevolence, kindness, and believed in the basic goodness of human nature, there lay a darker and more sinister aspect of the Chinese state that reflected the teachings of the Chinese Legalist school of thoughtwhich may be appropriately called the Chinese Machiavellians.

The principal architects of this school, including Kuan Chung, Shang Yang (rather than Shan Yang, as the book has it), Shen Pu Hai, and Han Fei Tzu, all believed in the reality of power, a healthy economy (essentially agriculturally-based), and a strong army in order for the state to survive. They believed in the unabashed use of brute force and intrigue to gain power and hold on to it. Furthermore, a basic distrust of human nature justified the ruler's use of strict laws and harsh punishments to govern his state and control his people. This is diametrically opposed to the teachings of the Confucians, who believed in the use of humanity and righteousness in instilling a sense of shame, a sense of right and wrong in the people. The Legalist rulers were not interested in educating their people, or learning the rules of propriety, or the etiquette of civil discourse. Ministers, rulers, and dynastic founders of later generations, who followed the Legalist tradition, were not ashamed to go counter to the teachings of Confucianism in their actions.

According to the Bloodworths, a husband-wife scholar journalist team, the ruler "must be cold-blooded in his judgments, trusting none. The carriage maker wants men rich, the coffin maker wants men dead. This is not a matter of love and hatred, but of profit and loss..." (75) In broad strokes, the authors paint the portraits of founding rulers of dynasties, generals, statesmen, and resourceful, ambitious women from consort families who clawed their way to power, having little regard for the teachings of Confucius, until they attained positions of power. In politics the world over, no matter whether it be Confucian or Legalist, Catholic or Protestant, secular or religious, even in seat of the papal authority murders, assassinations, alliances, and court intrigues fill the pages of human history. The history of the Chinese state has had more than its share of these machinations.

The book is divided into four parts: Thinking (3-84), Fighting (87-194), Ruling (195-290), and Analyzing (293-321). Part One is a succinct discussion of the major schools of thought that existed in China before the unification of China under the Ch'in Dynasty in 221 BCE. These schools of thought, including Confucianism, Taoism, Mohism, and Legalism, laid the intellectual foundations of China for the next two millennia. The interplay of these schools of thought seesawed back and forth in the long course of Chinese history. In periods of chaos and disunion, Taoism held sway. During times of peace, Confucianism reigned supreme. When the struggle for power was most intense, Legalism inevitably would rear its head.

Part Two focuses on the art of war in the China. Even though it is not a favorite subject of any of the major schools of thought, every school, except probably Confucianism, recognized the inevitability of fighting and war in real life. It took the mind of a military genius like Sun Pin, however, to formulate the principles of fighting in his famous work of military strategy, The Art of War. The book became a manual for many rulers, generals, and statesmen. It emphasized flexibility, understanding the ways of nature in fighting, and knowing when to fight, retreat, and negotiate. The classic struggle between Liu Pang (founder of the Han Dynasty) and Hsiang Yu (the haughty, aristocratic general) is a good case study of the struggle for survival between the old and the new:

Whereas Hsiang Yu was forthright, obstinate and overbearing, loyal to his own peculiar sense of honor, a capable commander determined to cut his way to the top, Liu Pang was a mediocre general but always listened to advice. A rough-tongued, openhanded rascal who quickly attracted affection, he concealed his cold appraisal and crafty manipulation of his fellow men behind a mixture of coarse good humor, warm fallible humanity, and bold presumption, according to mood. (113)

It is men of the latter kind who won the ultimate struggle for survival. Liu Pang defeated Hsiang Yu and eventually became the founding ruler of the Han Dynasty. To him winning was more important than sticking to the traditional etiquette of war.

Part Three of the book is on the art of ruling the state, or statecraft. During the time of the Tang Dynasty (618-908 CE), even though the foundations of the empire had been laid, the struggle for power among factions in the court was intense. The Tang Dynasty, generally known for its high culture, refined music and poetry, and cultural and religious open-mindedness, also had its share of murders, assassinations, and intrigue. The second emperor, Li Shih-min, because he was the second son and not the first in line, had to fight tooth and nail for the throne. Being a gifted general and political strategist, he knew how to play the political game: "...while his realm might be administered with Confucian magnanimity, rewards and punishments were precisely defined and the law strictly applied. Death and banishment dominated the list of corrections, and a whole clan could be collectively condemned and executed in cases of conspiracy and insurrection." (210) Li Shih-min came to the throne by cutting down his two brothers and annihilating all their male offspring, and finally forced his father, the founding emperor, to abdicate in his favor.