www.headofzeus.com

CALL TO ARMS : H. H. Kitchener, legendary soldier turned Secretary of State for War, as portrayed in the centurys most famous recruiting poster, September 1914. Kitchener saw it would be a long war requiring millions of men to fight it.

To my daughter Milena,

in her own right

THERE MAY BE TROUBLES AHEAD : King George V and Queen Mary visiting Ireland, 1911 the last British monarch to do so until his granddaughter Elizabeth II a century later.

Contents

SITTING COMFORTABLY? Prince Victor Duleep Singh and Mrs Henry Coventry and friends rest during a pheasant shoot at Stonor Park near Henley-on-Thames, November 1911. Indias upper crust were welcomed by their English counterparts.

We have long since ceased to think of the Edwardian era which most historians now see as being bookended by the death of Queen Victoria in 1901 and the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, rather than merely the reign of the eponymous King Edward himself as an age of tranquillity, comfort and languid leisure; a period typified by ladies with parasols in long white muslin skirts, green lawns under endless summer skies, and chaps in boaters or cricket whites, shooting at nothing more offensive than a passing pheasant.

In his play Look Back in Anger (1956) John Osborne sneers at his alter ego Jimmy Porters disapproving father-in-law Colonel Redfern as one of those sturdy old plants left over from the Edwardian wilderness who just cant understand why the sun isnt shining any more. Grudgingly, though, he admits that in retrospect the Edwardians had made their world look pretty appealing. Two decades previously, the historian George Dangerfield, in his seminal study The Strange Death of Liberal England (1935), had exploded the myth of Edwardian stability and progress, revealing an England marked by three major upheavals: the rearguard battle conducted by the Tory party and their Ulster Unionist allies against the reforms, including Irish Home Rule and a rudimentary welfare state, introduced by Asquiths Liberal government; the struggle for votes for women led by the Pankhurst family; and the strife and strikes racking industry led by militant trade unionists. These convulsions had combined in a perfect storm of unrest which had only been halted by the greater tempest of the war in 1914.

In this book I have tried to present a picture of the nation as it was on the eve of war, concentrating on the figures and developments which historians aided by the remarkable wisdom of hindsight have deemed to be outstanding. Like Dangerfield, I have given due weight to the major political and social issues of the year the Ulster crisis, the suffragettes and the growing fears of European war but I have also highlighted some of the undercurrents that, little noticed at the time, have since come to characterize our view of that year from the perspective of the past century. I have looked in some detail at the artists of the age the poets, painters and sculptors whose self-conscious modernism threatened to blow away the cosy certainties of an era already outmoded before the first guns of August had spoken and whose work foreshadowed and prophesied the disasters that lay in wait just around the corner.

SCRUBBING UP : boys cleaning coal at Bargoed, South Wales, where bitterly fought strikes and labour disputes had reached a violent climax by 1914.

What was it really like, the England of 1914? An orderly garden party about to be interrupted by a devastating thunderclap and cloudburst, or a seething mass of unresolved conflicts and contradictions racing towards inevitable destruction? The evidence of cold, hard statistics suggests the latter. Contrary to the sepia images of lazy country house weekends, out of a population of just over forty-six million the vast majority of British people belonged to the impoverished working class, living cheek by jowl in huddled poverty in the cities or eking out a bare existence on the sufferance of their landlords in a countryside where most land was privately owned and jealously guarded.

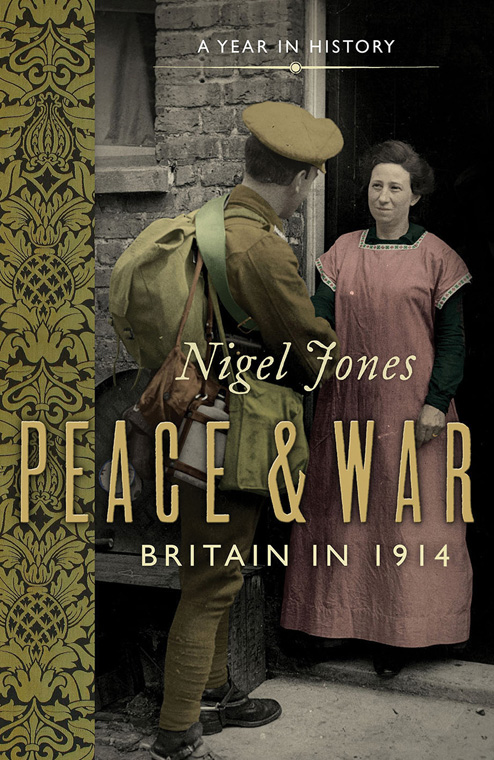

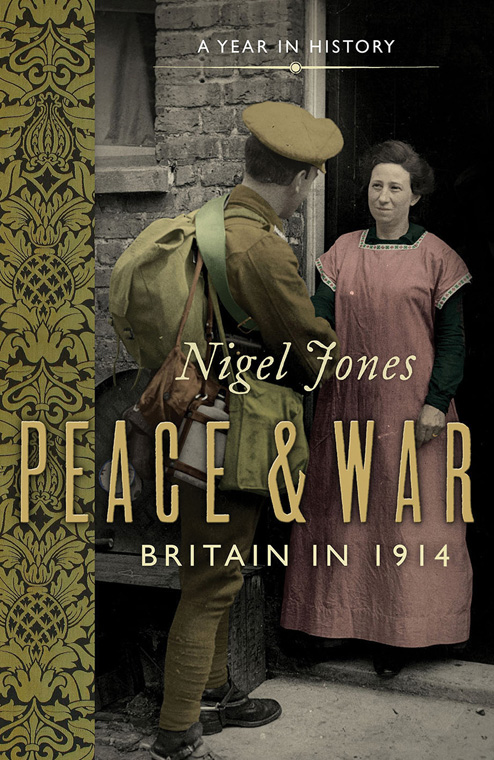

As summer came into full bloom at the beginning of August 1914, the last weekend of the old world was crowded with sporting fixtures. Fashionable race-goers gathered at Goodwood on the Sussex Downs; yachtsmen raced their craft on the Solent in preparation for the Cowes Regatta; at Canterbury and Hove, Kent and Sussex were playing at home.

Watching Sussex play Yorkshire at Sussexs hallowed County Ground in Hove was the future playwright and novelist Patrick Hamilton, whose prep school overlooked the ground. The home side were doing well. The previous day Joe Vine and Vallance Jupp had enjoyed an unbroken second-wicket partnership of 250 runs. Then, just after 3 p.m., the spectators heard the blare of martial music. A file of khaki-clad soldiers appeared, preceded by a marching band. Ignoring the match, the troops strode across the greensward and onto the pitch itself, where they turned and wheeled in formation to the bellowed commands of a regimental sergeant-major. The cricketers stood around gaping, unable to comprehend that the gentle activities of an England at peace were being brutally shoved aside. In his novel The West Pier (1952) Hamilton noted:

This entirely unnecessary, gratuitous and largely bestial assault upon the players (curiously akin in atmosphere to the smashing up of a small store by the henchmen of a gangster) beyond doubt ended in the victory of the aggressor though at the time of its happening very few people present were able vividly or exactly to understand what was taking place... [We] inhaled unconsciously the distant aroma of universal evil.

As the shadows lengthened across the County Ground and the umpires drew stumps, the crowd making its sheepish way home knew that the party really was over.

TOWARDS THE WEIR : punters on the Thames enjoy tranquil waters, 1914

HAYMAKING near Ambleside, Westmorland, 1910. But the harvest scene was deceptive: such pastoral peace hid grinding rural poverty and squalor.

On New Years Day 1914, the strong man of Britains Liberal government, Chancellor of the Exchequer David Lloyd George, gave his thoughts on the coming year to the Daily Chronicle , a top-selling popular newspaper that was effectively the house organ of Lloyd Georges radical wing of Liberalism.

The chancellors message was soothingly reassuring, his normal tone of aggressive eloquence muffled by the olive branch that he bore in his beak as a dove of peace. Contrary to recent fears, he told his interviewer, the likelihood of conflict in Europe was diminishing, not increasing. Any signs of strain in Anglo-German relations were subsiding owing largely to the wise and patient diplomacy of Sir Edward Grey an emollient reference to Lloyd Georges cabinet colleague, the foreign secretary. Thanks to this new spirit of harmony, the chancellor continued, Sanity has been more or less restored on both sides of the North Sea.

Next page