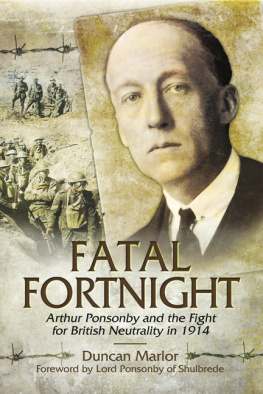

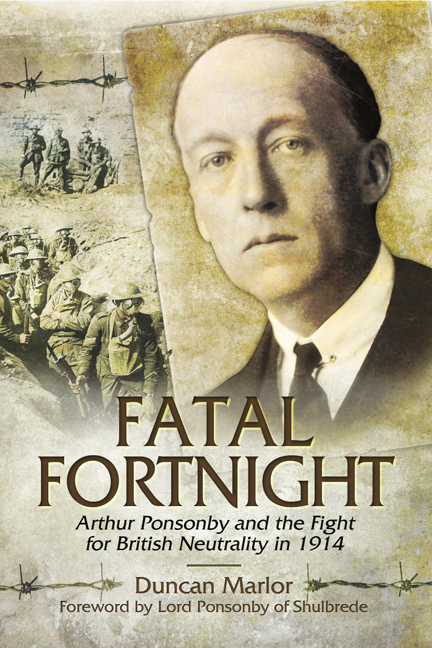

Fatal Fortnight:

Arthur Ponsonby and the Fight for British Neutrality in 1914

This edition published in 2014 by Frontline Books,

an imprint of Pen & Sword Books Ltd,

47 Church Street, Barnsley, S. Yorkshire, S70 2AS

www.frontline-books.com

Copyright Duncan Marlor, 2014

Foreword Frederick Ponsonby, 2014

The right of Duncan Marlor to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

ISBN: 978-1-47382-286-3

eISBN: 9781473838123

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

CIP data records for this title are available from the British Library

For more information on our books, please visit

www.frontline-books.com, email info@frontline-books.com

or write to us at the above address.

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

Typeset in 11.2/14 pt Minion Pro

Contents

Illustrations

| Plate 1: |

| Plate 2: |

| Plate 3: |

| Plate 4: |

| Plate 5: |

| Plate 6: |

| Plate 7: |

| Plate 8: |

| Plate 9: |

| Plate 10: |

| Plate 11: |

| Plate 12: |

| Plate 13: |

| Plate 14: |

| Plate 15: |

| Plate 16: |

Acknowledgements

The genesis of this book goes back over more than a decade and a large debt of gratitude is owed to many people. First and foremost I must thank the Ponsonby family for its unfailing support, especially Laura Ponsonby and Kate Russell, Arthur Ponsonbys grand-daughters, both for their generous hospitality at Shulbrede Priory and their considerable help with the Shulbrede archives, and valuable suggestions, including the diary of Sir Hubert Parry, which had not occurred to me but which turned out to be priceless. Also I must thank Frederick, Lord Ponsonby of Shulbrede, great-grandson of Arthur Ponsonby, for the foreword that he has kindly provided, which gives a present day parliamentarians perspective on his ancestors story.

I thank Robin Dower, grandson of Sir Charles Trevelyan, for his kind help with details of the Trevelyan family; Wallington Hall, Northumberland, especially Lloyd Langley; and the Robinson Library, Newcastle University, especially Geraldine Hunwick, Archivist and Special Collections Librarian, for help with Trevelyan family archives and visual material and to the Trevelyan Family Trustees for their permission to use this.

Thanks are due to Mark Outhwaite, great-grandson of Robert Leonard Outhwaite, for help in respect of details of the Outhwaite family; and to Edward Milligan, former Librarian of Friends House for his assistance, insights and personal memories regarding Thomas Edmund Harvey.

I am grateful to David Kynaston for reading through the material and for his helpful suggestions. I thank Sir Tam Dalyell, former Father of the House of Commons for his interest over some years and for sharing family insight into Sir Edward Grey.

Special thanks also are due to Colin Harris, Superintendent of Special Collections at the Bodleian Library, Oxford, for his kind help over some years regarding the Ponsonby Papers and other collections. In thanking him I thank the many librarians and archivists who have made possible the researches on which this book is based.

At Frontline/Pen and Sword I would like to thank Michael Leventhal, Kate Baker his assistant, and their colleagues, for their support for this project and their excellent work and guidance in bringing the book to publication.

Foreword

By Frederick Ponsonby,

4th Baron Ponsonby of Shulbrede

DUNCAN MARLORS ACCOUNT of the lead-up to the First World War tells the story of the role of backbench MPs in the parliamentary debates that led up to war. Arthur Ponsonby, my great-grandfather and at the time a Liberal backbencher, led the fight for British neutrality. The book challenges the sense of inevitability and unity of purpose which political leaders of the day, pro-interventionist newspapers and many historians sought to present to subsequent generations. As Duncan Marlor says, there was real drama in the parliamentary debates and votes that set Britain on course for war.

In writing this foreword some 100 years later and with memories of parliamentary debates on recent wars in my mind, it is interesting to try and draw some comparisons. I shall limit myself to three.

The first is a question of the scale of the proposed wars: while in 1914 few could have predicted the true horror of the war to come it was nevertheless true that the British government and British people were ready to sustain losses far higher than would ever be contemplated today. Senior officers and many MPs would have fought a number of wars in their careers and while there had not been a general war in Europe involving Britain since Napoleonic times, they would have been steeped in the military history of large-scale European wars. They would have considered that war was to protect British interests through its empire and maintaining the balance of power in Europe. Contrast that with todays wars where the fight is not between nation states acting in alliance to protect their own interests but between coalitions of states, led by America and acting in defence of human rights as defined by international treaty. The interpretation of UN resolutions is central to the justification for todays wars.

My second comparison is between public opinion then and now: the thrust of Duncan Marlors narrative is that there was far more anti-war feeling in the lead-up to the First World War than has hitherto been acknowledged. Whilst this is true and he presents a compelling argument, it remains the fact that most of the anti-war rebels lost their seats in the 1918 general election. It also remains true that there was plenty of prowar sentiment and even violent opposition to peace rallies, something which would be unthinkable for any of the wars undertaken in recent years. I would suggest that being anti-war in 1914 took greater courage with greater risk of being socially ostracised than being anti-war today. This is probably because the sense of threat was far greater; the very existence of Britain as an independent country was in question in 1914 whereas none of the wars in recent years threatened the state itself.