FIRST WORLD WAR BRITAIN

19141919

Peter Doyle

CONTENTS

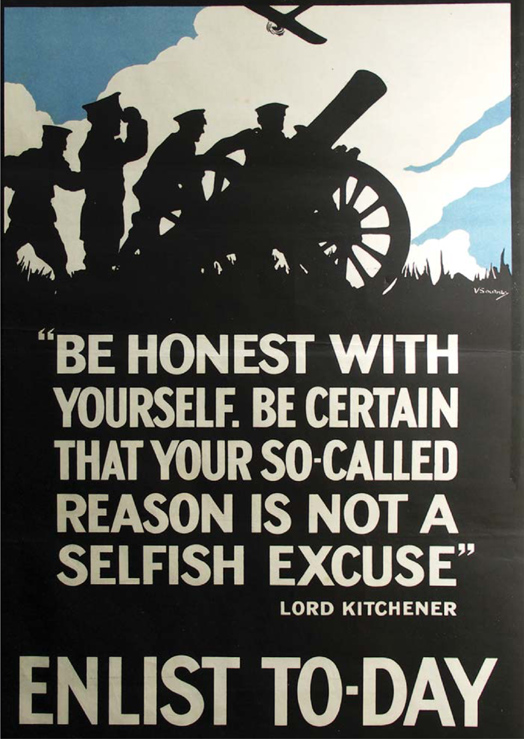

Typical output of the Parliamentary Recruiting Committee. Such posters played heavily upon the conscience of men not in uniform.

PREFACE

P oppies, mud, shrapnel, heavy green clouds of gas, tangled wire, unbearable noise and twisted, torn, wrecked bodies: unmistakeable images that conjure up the Western Front, 191418, to all of us. Almost a century on, the nightmare of the war remains vivid in our imaginations.

Soldiers returning home from the trenches, on leave or invalided out of the army, found themselves in a world that had little understanding of what they had lived through. Many struggled to adjust to normality.

Yet the war could not have been fought without a huge effort back home, and the needs of the first total war brought radical change to many aspects of life in Britain. As young men went abroad en masse to fight and die, their jobs had to be filled, taxes and all kinds of charitable efforts had to be raised, extraordinary demands for supplies and materiel had to be fulfilled, morale had to be maintained and somehow, family life had to go on. Meanwhile, the country that had a proud record of not having been threatened by war or invasion for a century suffered a new threat aerial bombardment from the German zeppelins while U-boat attacks meant that imports were cut, shortages loomed and prices, especially food prices, soared. The effects were not so dramatic as those at the Front, but they were just as profound.

The legacy of the revolutionary changes in the power of government to determine the economy lives with us still, as do the licensing laws which restricted opening hours at pubs and were inteneded to boost productivity. Many charitable activities were developed during the war, not to mention medical advances including the beginnings of plastic surgery and the beginnings of modern psychology.

The well-known military historian Peter Doyle provides a ideal guide to those troubling times, investigating the effects of war on family life, work, entertainment, education and many other dimensions in a rounded, brilliantly illustrated survey of the war years.

Peter Furtado

Series Editor

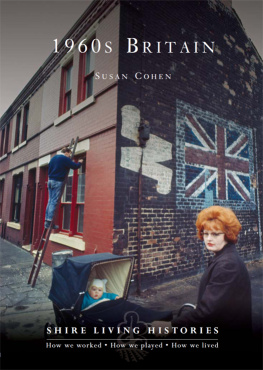

The Edwardian Summer: metaphor for the end of an era in August 1914. Britain carries on as normal at Southend-on-Sea in the last month of peace before the first of war.

BRITAIN IN THE FIRST WORLD WAR

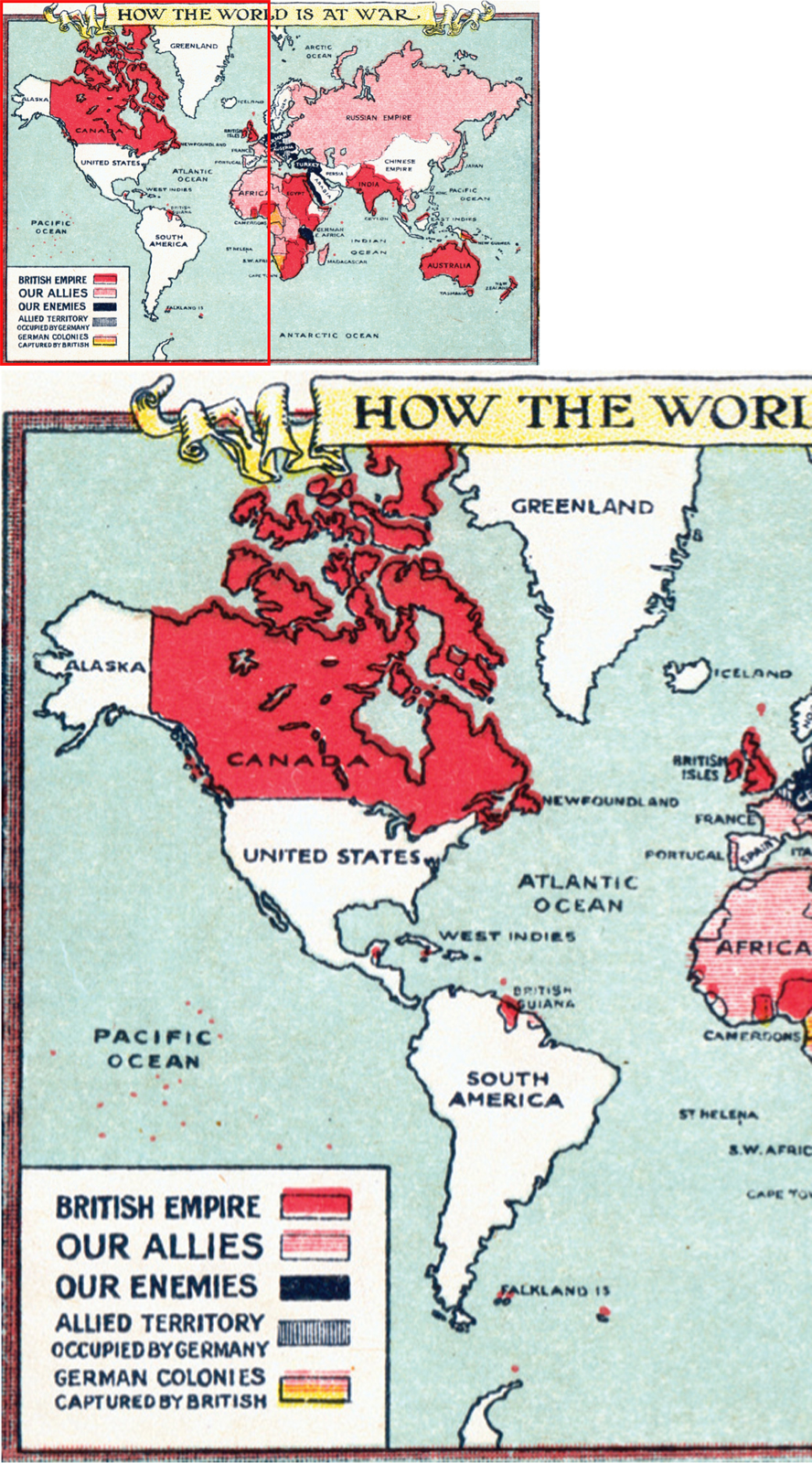

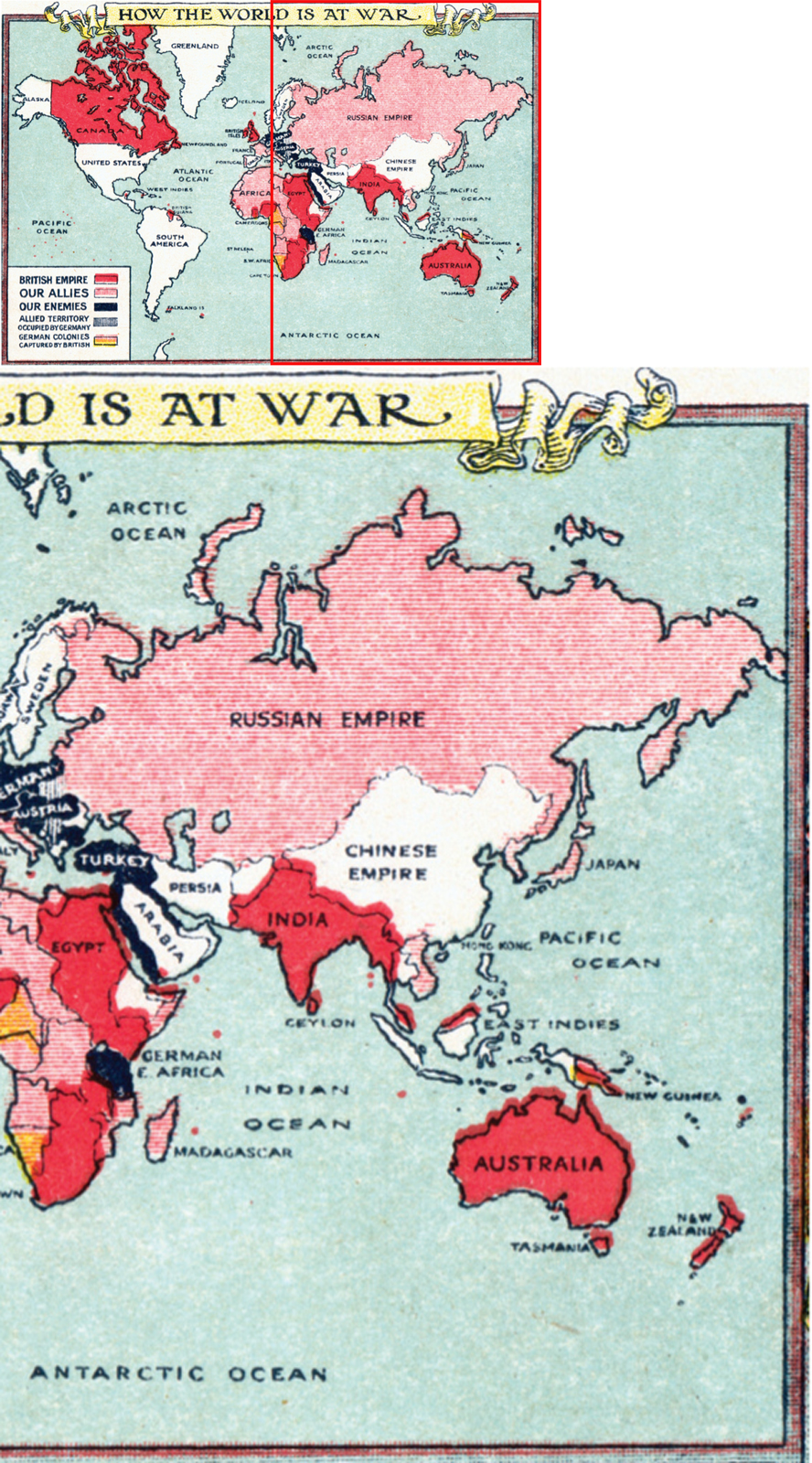

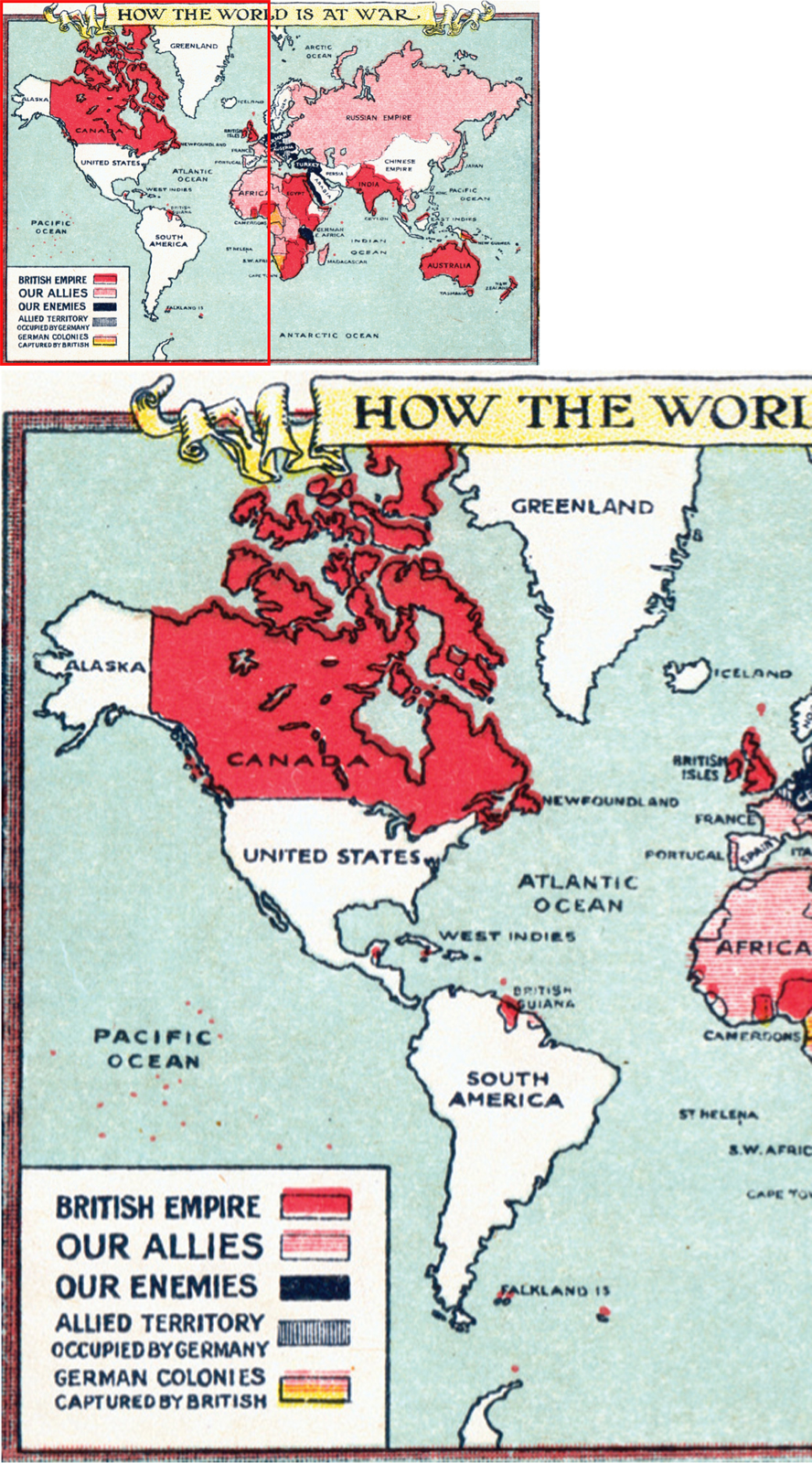

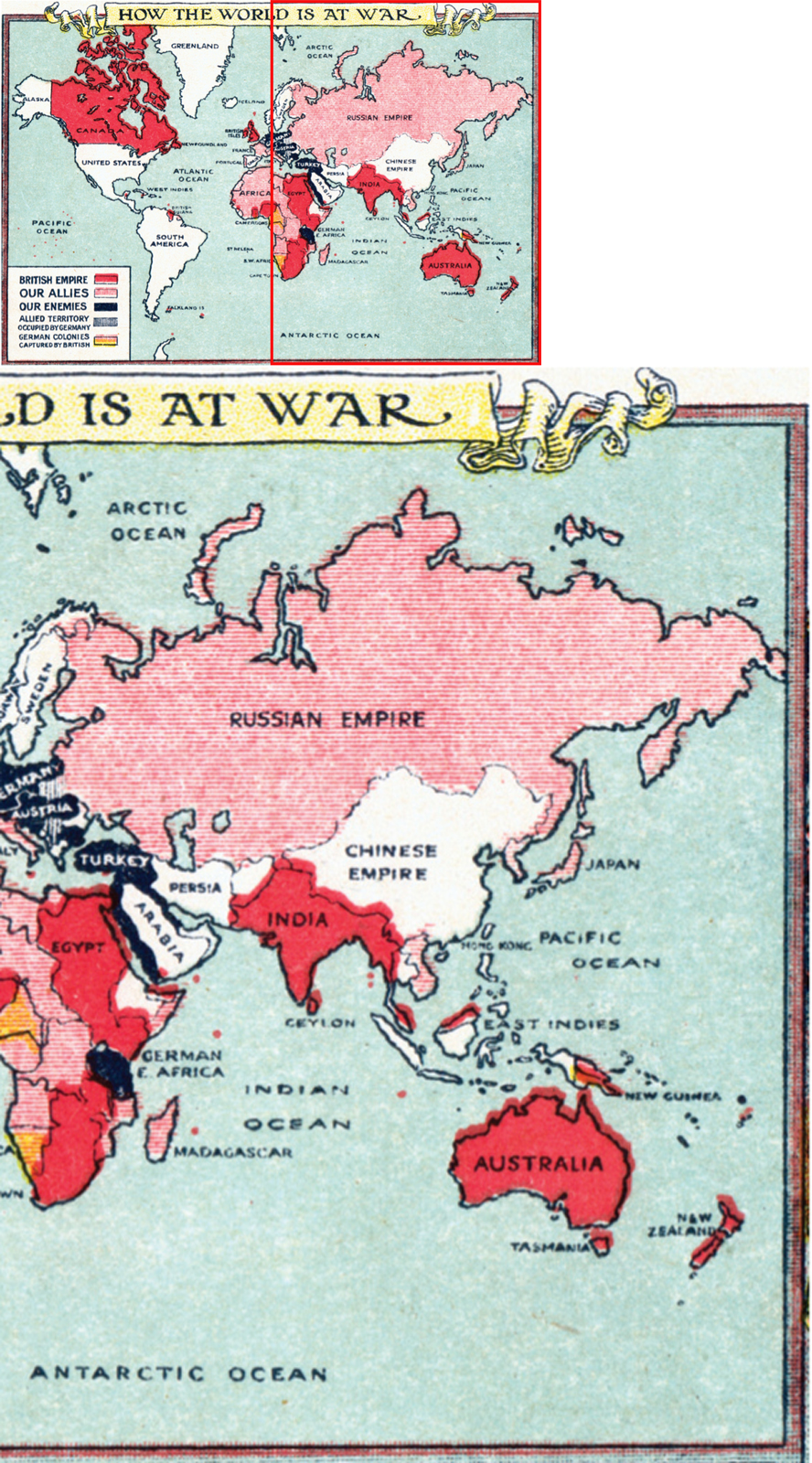

B RITAIN had undergone many changes in the years before the start of the Great War (as the First World War was known at the time, and as it is coming to be known again). By late Victorian times, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland had extended its reach across the globe. As every schoolchild knew, the sun was never likely to set on the British Empire, its red splash depicted on maps across five continents signifying British territories that extended into hemispheres north and south, east and west. With India the jewel in the crown of the Empire, and possessions and colonies far and wide, the imperial city of London had become a truly global city. Britain was at the height of its influence.

With the ascent of Edward VII to the throne in 1901, there was a distinct change in atmosphere. Though society still had the rigid class structure so evident during the reign of Victoria, the Edwardian era was an interval of positivity, with a playboy king leading a fashionable upper-class elite. There were changes for the lower classes too; the new Liberal government of 1906 swept away old laissez-faire attitudes to welfare, summoning changes that would see the birth of an incipient welfare state. This atmosphere would continue through to the eve of the Great War; and perhaps because of this (even with King George V coming to the throne in 1910), it is usual to consider the Edwardian era as extending to the outbreak of world war.

If the late Edwardian, pre-war, period was marked by the consolidation of Britains global influence, it was also marked by a consideration of its relations within wider Europe. Hitherto typically isolationist, and dependent upon its navy for defence, Britain had been aloof from European politics for decades. Yet with Queen Victorias wider family being distinctly European in character (the marriages of her nine children tying them into royal elites from Russia and Germany to Norway, from Romania to Spain), it is not surprising that Edwards association with the fashionable elite of European society would help build bonds and alliances. In a last major act of international diplomacy by a British monarch, the king would be a driving force in the development of the Entente Cordiale between Britain and France in 1904 (and a Triple Entente between Britain, France and Russia in 1907), a bond of friendship that would have a significant impact on Britains direction in war just ten years later. It would also be significant in terms of Britains relationship with another neighbour Germany.

The British Empire a splash of red across the map and its enemies, 1914.

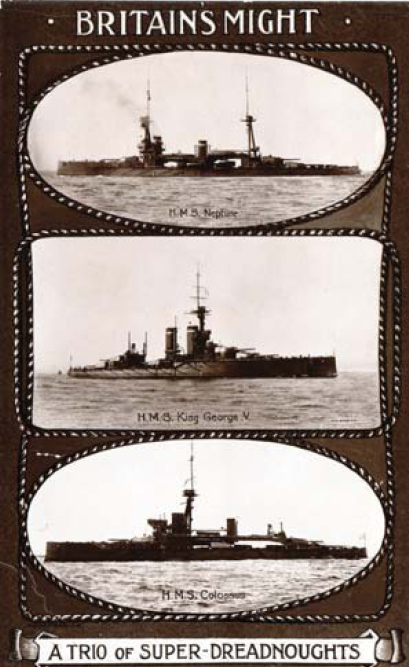

Three super-dreadnoughts. The British navy was seen as the primary strength of Britain, its main defence.

Though close links with Germany had been mooted in the early years of the kings reign (with Edwards sister, Princess Victoria, being the empress of Germany until her death in 1901, and mother of Kaiser Wilhelm II), Edward had turned his back on the idea of a triple alliance of the three major European nations. Kaiser Wilhelm II was a cousin of King George V but there was little in the way of family warmth expressed in his direction. The kaiser was just a little too fond of grand titles and fancy uniforms for the conservative British. Instead, the British press was generally antagonistic towards Germany, with depictions of stereotypical swaggering, sabre-rattling, Prussian militarists. Suspicious also of German intentions, the British government took particular exception to the developing arms race created by the kaisers desire to build an effective navy. This was a distinct warning shot across the bows, a growing threat to British supremacy of the seas that could not be left unchallenged. Within this atmosphere there was much scaremongering over possible German invasion plans, and much antagonism directed across the channel by the new British tabloid press. With William Le Queuxs fictional tale, The Invasion of 1910, serialised in The Daily Mail, the die was cast for future war, the expectation of its coming strong.

Wartime bunting featuring the flags of the Triple Entente (Britain, France, Russia), and the country it was defending Belgium.