MUSEUMS IN BRITAIN: A HISTORY

Christine Garwood

Working-class access to Victorian and Edwardian public museums was encouraged by changing patterns of work and leisure, as well as improved levels of education and literacy.

SHIRE PUBLICATIONS

Old-fashioned display of objects in the Victoria & Albert Museum, Kensington.

CONTENTS

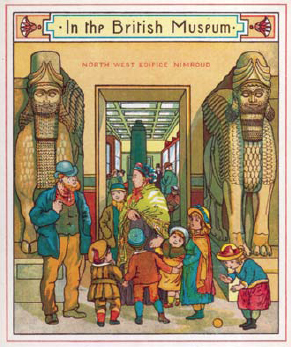

The crowds that packed the British Museums blockbuster Treasures of Tutankhamun exhibition in 1972 reflect the enduring appeal of museums and their central place in learning, research and scholarship as well as popular culture.

INTRODUCTION

A museum is a non-profit, permanent institution in the service of society and its development, open to the public, which acquires, conserves, researches, communicates and exhibits the tangible and intangible heritage of humanity and its environment for the purposes of education, study and enjoyment.

International Council of Museums

Museums enable people to explore collections for inspiration, learning and enjoyment. They are institutions that collect, safeguard and make accessible artefacts and specimens, which they hold in trust for society. Museums Association

I N N OVEMBER 2012, Londons Victoria and Albert Museum announced that its next blockbuster exhibition would be David Bowie Is, an international retrospective of the innovative musician and cultural icon across five decades, benefitting from unprecedented access to his private archive. In the week leading up to the exhibitions opening, it became clear that this had become the fastest-selling spectacle in the museums history, with in excess of forty-two thousand timed tickets sold to the public in advance, outstripping the populations of the Shetland and Orkney Islands combined and more than doubling the number of such sales for previous exhibitions. Bowies popularity and influence aside, the episode demonstrates not only the increasing appeal of museums and their place in contemporary culture, but also just as sharply their changing role. Although the exhibition was the latest in a line of London blockbusters, from Manet to Pompeii, and museums have always collected and displayed the work of the contemporary and cutting edge, the sheer level of public interest and access illustrates the extent to which Britains cultural institutions have developed over the last five hundred years. From the boltholes of connoisseurs and collectors to a source of gossip for tabloids, museums have retained much of their fundamental purpose while their role has in many ways been transformed. This book, albeit short, is an attempt to trace this story through a portrait of some of the major institutions, obscure enthusiasts and overarching trends that have served to shape the history of museums in Britain from the sixteenth century to the twenty-first.

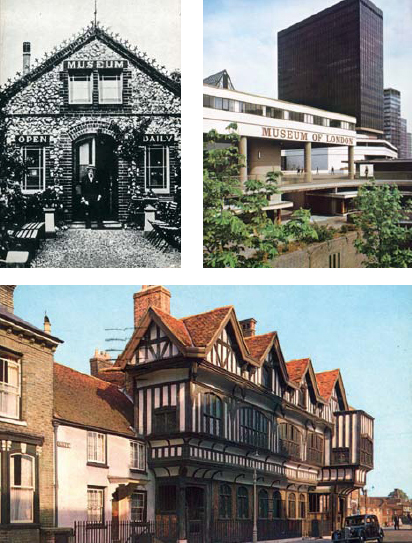

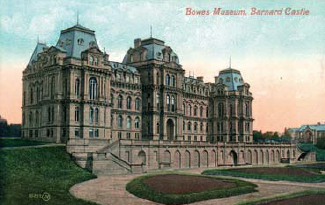

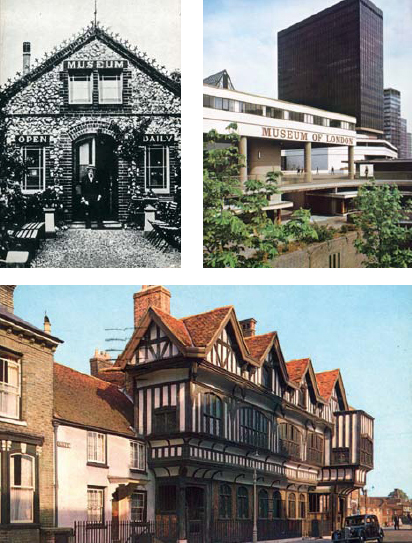

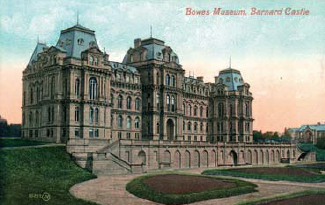

Museums and galleries can be found in a vast array of venues, big and small. Pictured here are the Museum of London at London Wall (top right), Southamptons recently restored Tudor House Museum (middle), the Bowes Museum at Barnard Castle (bottom), County Durham and the original museum of taxidermist Walter Potter (18351918), in Bramber near Steyning, Sussex (top left). Mr Potters Museum of Curiosities, as it was known, was based on his collection of stuffed animals often set in detailed dioramas such as Rabbit School and The Original Death and Burial of Cock Robin. By the mid-1980s, the collection had moved to Jamaica Inn, Cornwall, before being dispersed by auction in 2003, sparking public outcry.

From Liskeard to London, museums have become a key feature of the British cultural landscape, representing a host of subjects and passions developed by people and communities over time. With topics ranging from fans and lawnmowers to football and priceless art, museums can be found in almost every conceivable location village or town, abandoned church or even disused sardine factory, reflecting our fundamental desire to collect, safeguard and make accessible artefacts and specimens (Museums Association, 1998). While museums have their place as repositories of curiosities, as described in the 1836 edition of Samuel Johnsons Dictionary of the English Language, they are now also virtual venues without walls where visitors may have no immediate contact with objects at all. Whether they be esoteric or high-tech, the story of museums is therefore the story of human progress: our interests, our fascinations and our interpretations of our own history, in the context of broader developments and shifts.

The word museum itself has ancient roots, originating from the Greek Moo (Mouseion), a place or shrine dedicated to the Muses, the nine mythological guardians of history, astronomy and the arts. The word is most famously associated with the Musaeum of Alexandria (including the Library of Alexandria) established by Ptolemy I Soter or Ptolemy II Philadelphus in c. 280 BCE for music, poetry, philosophy and research, similar in purpose to a modern university. The actual practice of collecting dates back to the oldest civilisations however to ancient Babylon and the private collections of rare or curious natural objects and artefacts such as Ennigaldi Nannas museum of Mesopotamian antiquities dating from c. 530 BCE.

While the practice of collecting is age-old, the word museum was not used in English to mean a collection or building to display objects until the mid-seventeenth century, when it was applied to botanist and gardener John Tradescant (c. 15701638) and sons dazzling collection of rarities, which by various twists became the basis of the University of Oxfords Ashmolean Museum (1683). The extraordinary hoard, a wonder for contemporaries, originated in Tradescant the elders work travelling in Europe and North Africa looking for new types of plants to bring back for his employers in England, including the apricot, lilac and acacia trees. His search and his ark as the Tradescants treasure-filled Lambeth home was known underscores a deeper point: museums can originate from any number of human activities from passion to plunder, trading to religious mission, voyages of discovery or of conquest, scientific study, obsession or simple greed.

Early twentieth-century cigarette card depicting the etymology of the word museum from a place or shrine dedicated to the nine muses of Greek mythology. Museums in Britain fulfil a vital social function, both reflecting and shaping the story of the nation, and our collective understanding of the past.