Stanford University Press

Stanford, California

2012 by the Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University. All rights reserved.

This book has been published with the assistance of Loyola Marymount University.

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system without the prior written permission of Stanford University Press.

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free, archival-quality paper

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Woodson-Boulton, Amy, author.

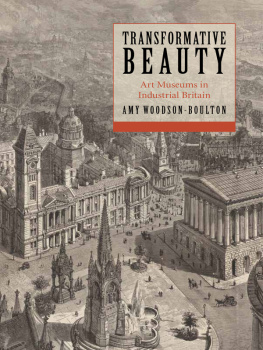

Transformative beauty : art museums in industrial Britain / Amy Woodson-Boulton.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8047-7804-6 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-8047-8053-7 (e-book)

1. Art museumsGreat BritainHistory19th century. 2. Art museumsGreat BritainHistory20th century. 3. Art and stateGreat BritainHistory19th century. 4. Art and stateGreat BritainHistory20th century. 5. Art and societyGreat BritainHistory19th century. 6. Art and societyGreat BritainHistory20th century. I. Title.

NI020.W66 2012

708.209034dc23

2011030708

Typeset by Bruce Lundquist in 10/15 Minion

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

It is a pleasure to be able to thank all of the institutions and individuals who have helped me to research, write, and publish this book over the course of many years. I am sincerely grateful for the administrative and moral support of the History Department at Loyola Marymount University; for publishing grants from the History Department, from Bellarmine College of Liberal Arts Dean Paul Zeleza, and from Chief Academic Officer Joseph Hellige at LMU; for support from the LMU Sponsored Projects Office, particularly from Cynthia Carr; for a Robert R. Wark Fellowship from the Huntington Library, Art Collection, and Botanical Gardens; for a Summer Stipend from the National Endowment for the Humanities; for summer writing grants and a Bellarmine Research Grant from Loyola Marymount University; for a summer writing grant from Juniata College; for an Edward A. Dickson Fellowship in the History of Art from the UCLA Art History Department; for a Walter L. Arnstein Prize from the Midwest Victorian Studies Association; for grants from the UC Centers for German and Russian Studies and European and Russian Studies, respectively; and for a Pauley Fellowship and other support from the History Department at UCLA.

Many librarians, archivists, and curators helped in the research for this book. Deep thanks go to Jane Farrington, Martin Ellis, Brendan Flynn, Zelina Garland, Victoria Emmanuel, and Tom Heaven at the Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery; to the staff at the Birmingham Central Library; to Christine Penney at the University of Birmingham Special Collections; to Melva Croal, Andrea Martin, Vincent Kelly, Sarah Skinner, and Tracey Walker at the Manchester City Art Gallery; to the staff at the Manchester Central Library Local Studies, Archives, and Art Library, especially David Taylor, Judith Baldry, Sarah Sherratt, Katherine Taylor, and David Govier; to Joseph Sharples and Nathan Pendlebury at the Walker Art Gallery; to Mark Pomeroy at the Royal Academy Archives; to the staff at the Tate Archives and Amelia Morgan at Tate Images; to Carmen Prez Gutirrez at the Museo Nacional del Prado and to Juan Luis Sanchez for his assistance; and to the staffs of the Liverpool Central Reference Library, the National Art Library, the British Library, the Colindale Newspaper Archive, the Huntington Library, and the Interlibrary Loan offices at UCLAs Young Research Library and at LMUs William Hannon Library.

Many scholars have been very helpful at all stages of this project. In Britain I was helped in particular by Gordon Fyfe, Kate Hill, Rohan McWilliam, Edward Morris, Susan Pearce, Giles Waterfield, James Moore, and Dungo Chun. At UCLA, I am grateful to participants in the European History and Culture Colloquium, where I presented my first drafts; my particular thanks go to Professors Lynn Hunt, Margaret Jacob, Muriel McClendon, Peter Reill, Geoffrey Symcox, Teo Ruiz, Russell Jacoby, and Gabi Piterberg, and to Drs. Gabriel Wolfenstein, Eric Johnson, John Mangum, Andrea Mansker, Ben Marschke, Kelly Maynard, Britta McEwen, Peter Park, Courtenay Raia, Patricia Tilburg, and Claudia Verhoeven. Additional scholars who advised and helped to shape the project at the earliest stages, and deserve great thanks, include Sylvia Lavin, Robert Wohl, Anthony Vidler, David Sabean, and Dianne Sachko Macleod. Since I joined the faculty at LMU, the British History Reading Group in Los Angeles has been a welcoming and generous source of professional support, and special thanks go to Erika Rappaport, Lisa Cody, and Philippa Levine for mentoring and hospitality. Vanessa Schwartz, Peter Stansky, Jordanna Bailkin, and Lara Kriegel gave me sound advice and thoughtful comments along the way, for which I am very grateful. My students, teaching assistants, and student researchers at LMU have performed multiple, much-appreciated tasks and pushed me to consider the big picture. My LMU colleagues have attended presentations and provided many ideas, hallway listening sessions, and (best of all) friendship. I also thank the many conference attendees who allowed me to test-run much of this material over the years. Finally, I am profoundly obliged to three stellar champions, whom it is difficult to thank sufficiently: Debora Silvermans work has been a constant inspiration, and I deeply appreciate her support of my career generally and of this project specifically. Tim Barringer has become an invaluable source for thinking about art history and history, and I have felt extremely lucky to have his assistance, advice, and encouragement. Tom Laqueur has been an unbelievably buoyant and attentive ally, reading drafts and book proposals and galvanizing me into finishing the manuscript (particularly when he heard I was pregnant again).

My friends in Britain have been more valuable than perhaps they realize in supporting my research and writing. They have of course deepened my understanding of British culture, but they have also given me emotional sustenance, many nights of lodging, and countless meals. Thanks to Claire and Mark Johnston, Helen and Andrew Scott, Stephen Metcalfe and Mark Ford, Dominic Wilson, Paul and Anna Spyropoulos, Rachel Board, Andrew and Emma Watson, Matt and Wendy Turner, Daniel Castle, Zelina Garland, and David Rowan (who supplied last-minute photographs of Birmingham institutions). I cannot thank my English family enough: Charonne and Jeremy Boulton, Hannah Boulton, Richard and Ava Rose Jones, and Marje Aston.

Norris Pope, Sarah Crane Newman, and Carolyn Brown at Stanford have been delightful to work with, and copyeditor Jessie Dolch performed a wondrous job of polishing this text that I have been poring over for so long. I am especially grateful to the two anonymous readers of the manuscript, whose comments enabled me to see how, finally, I could finish it to my own satisfaction. Of course, as ever, any errors or omissions remain my own.

I dedicate this book to my American and English families, who have quite simply made this long project possible, and who have helped me to think about the public role of culture and the arts. Charonne and Jeremy Boulton have provided much good humor, marvelous hospitality, and outstanding generosity. My mother, father, and brother have commented on countless drafts and maintained a remarkable and consistent enthusiasm. (Now that I am myself a mother, it is a bit staggering to realize how much I owe my parents; how can I ever thank them enough?) Finally, my husband, Luke, deserves (like all faculty spouses) an honorary degree and at least one really nice night out. He saw me through graduate school and tenure, and his coparenting has allowed me to revel in my two rambunctious and wonderful boys, Felix and Leo, while still engaging in historical scholarship. I am so grateful to these three for giving me the time to work, and for always insisting that I find time to play.