NATURES

MUTINY

NATURES

MUTINY

How the Little Ice Age of

the Long Seventeenth Century Transformed

the West and Shaped the Present

PHILIPP BLOM

translated from the German by the author

LIVERIGHT PUBLISHING CORPORATION

A DIVISION OF W. W. NORTON & COMPANY

Independent Publishers Since 1923

NEW YORK LONDON

Fifth is the race that I call my own and abhor.

O to die, or be later born, or born before!

This is the Race of Iron. Dark is their plight.

Toil and sorrow by day are theirs, and by night

the anguish of death; and the gods afflict them and kill,

though theres yet a trifle of good amid manifold ill.

HESIOD, Works and Days

This is the terrible century about which Scripture speaks so clearly. It is the Iron Age, which breaks and subdues all things. The seven angels have emptied their vials over the earth, and they contained blasphemy, terror, massacres, injustice, treason.... We have seen and continue to see how realm rises against realm, nation against nation, plagues, famines, earthquakes, terrible floods, signs in the sun and the moon and the stars; the sufferings of nations through storms and thunderous waves.

JEAN-NICOLAS DE PARIVAL, 1654

Europe where the sun dares scarce appear

For freezing meteors and congealed cold.

CHRISTOPHER MARLOWE,

London, 1578

The lights and windows in the vault of the heavens often grow dark and will no longer shine and shed light on the worlds larceny / and they are longing with us for our salvation... the sun / the moon / and other stars / shine / less brightly than before / there is no true and lasting sunshine / no steady winter and summer / fruits and things growing from the earth no longer ripen as well / or are as healthy as they most likely used to be.

REVEREND DANIEL SCHALLER, Stendal, in Prussia, 1595

Twas a harsh cold winter here / you could catch birds and game with your hands.

Twas a hot and arid summer / and the crickets devoured everything in the field / which caused great price increases.

CHRISTOPH SCHORER, Memmingen, in Germany, 1660

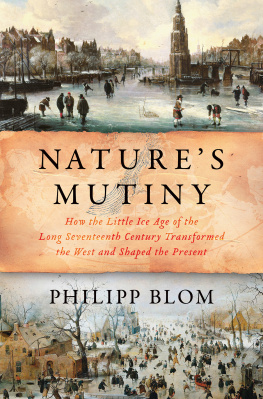

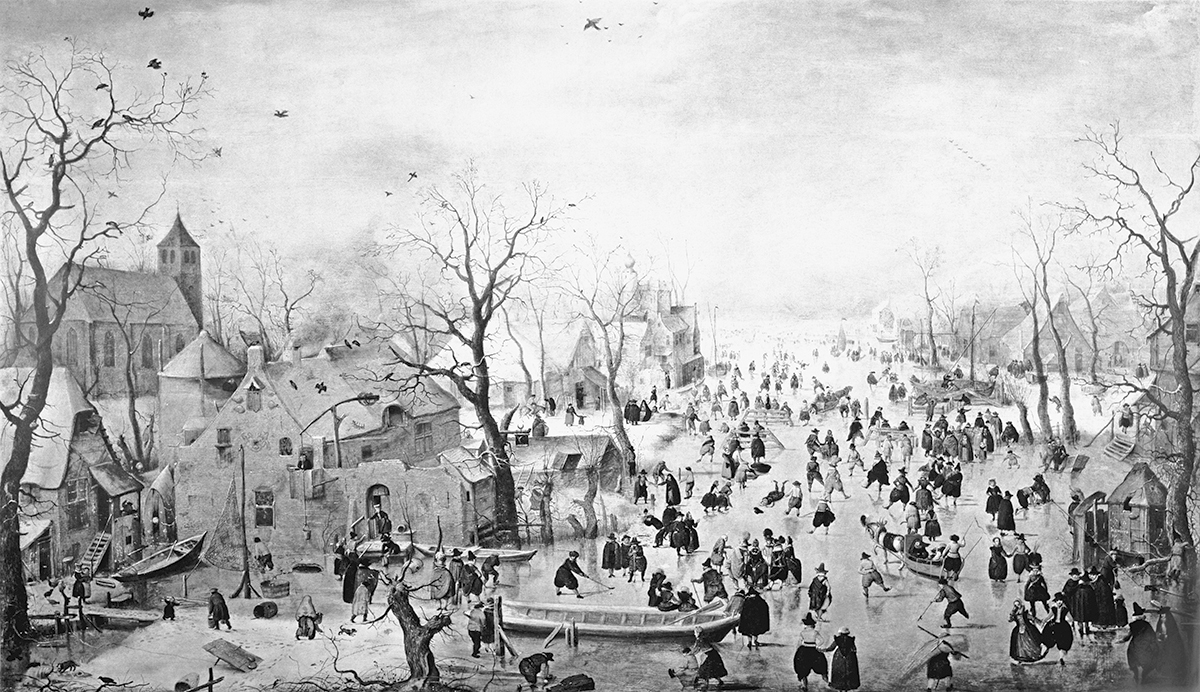

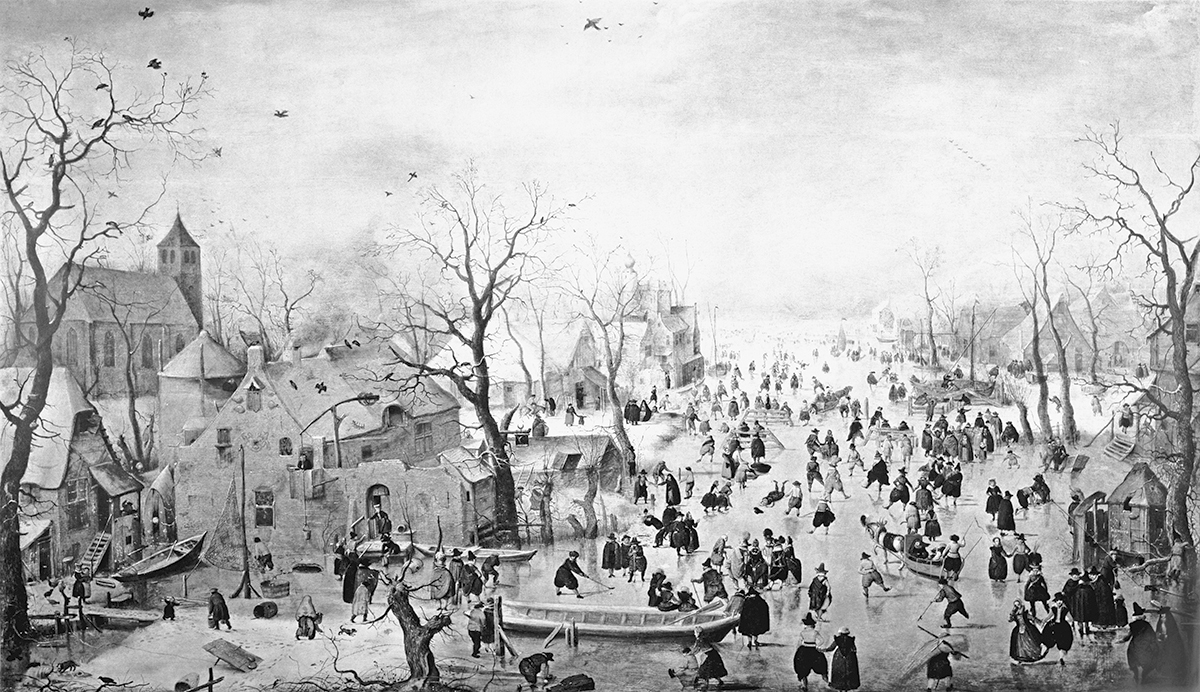

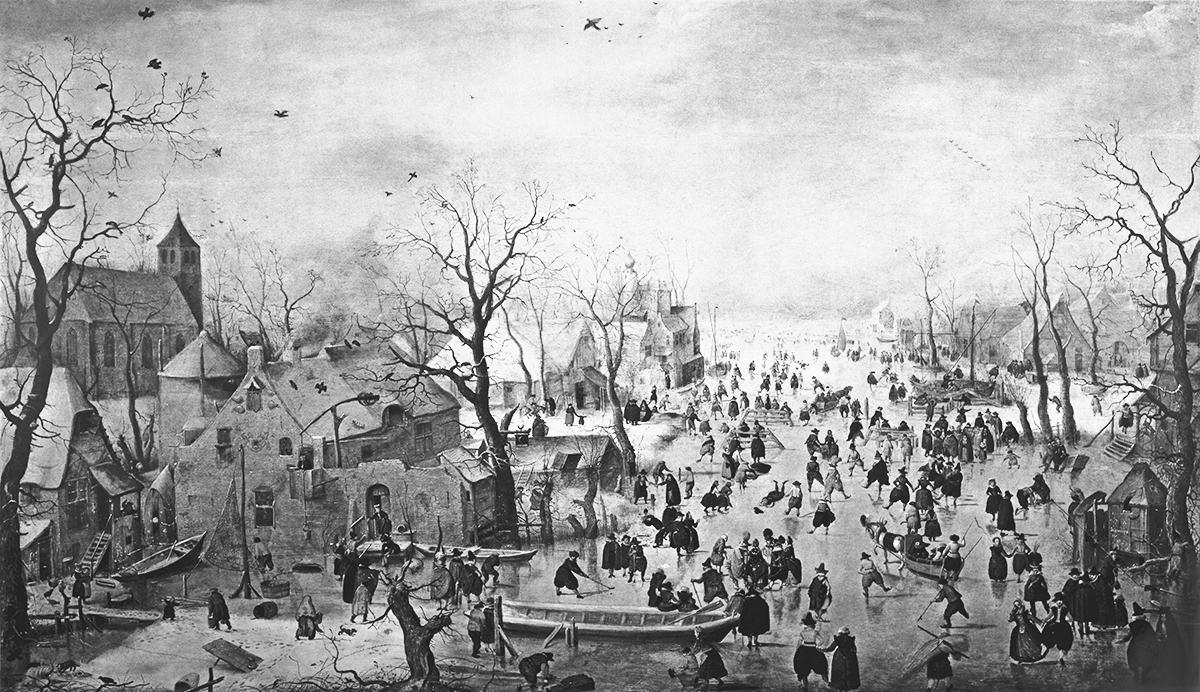

HOW HAPPY THEY ALL SEEM moving across the ice with the greatest of ease. They are either gliding on skates or luxuriously ensconced in horse-drawn sleighs sailing across the rivers polished parquet. Some huddle together in groups, talking among themselves; others are playing games. Wealthy gentlemen have their coats slung elegantly across their shoulders, and the ladies are wearing lace caps or wigs, or both. The simple folk are moving about in short jackets. There is no fire to warm their freezing limbs, but on this perfect winter day, no one appears to feel the cold.

The swarming, antlike image of life amid the frost seduces the eye; the landscape dissolves into a panorama of individual scenes. The villagers appear in all kinds of situationsfrom the two lovers in the haystack (are they both men?) to the naked behind poking out of a broken boat and a second bottom whose owner is half hidden by a willow tree; from the mother with her child in the foreground to the men playing golf, the reed cutter with his enormous load, and the young couple gliding hand in hand across the hard surface. A woman drinking from a beaker is one of the few figures whose face is revealed. Most of the villagers are moving away on their wooden skates with thin steel bladestoward the horizon, into a future that is little more than a sketch.

Slightly to the right of center stands an important-looking group in elegant, gold-embroidered garbladies with hoop skirts and tall wigs, gentlemen with precious ostrich feathers adorning their hats. A gray beggar attempts to stir their pity, but they show no interest. What are they doing on the ice in some godforsaken villagewithout a coach, without servants? How did they get here? And what exactly are all these people doing? They are not celebrating any special event or feast day, not Christmas and not Carnival. It is not even Sundaythe church looming in the background is eerily dark.

The longer one examines this panorama, the less plausible it becomes. The initial impression of realism grows into an understanding of allegory. A whole society is on the same ice hererich and poor, men and women, children and the elderly, masters and servantsall equalized by frost and cold but seemingly untouched by it. Only the animal cadaver in the left corner hints that death will leave its mark on this idyll; the bird trap made from an old door is ready to snap shut and crush its next victim, reminding the viewer that earthly pleasures are transientCarpe diem (Seize the day). An empty beehive stirs latent memories of lazy summer afternoons with blazing, colorful blossoms. Soaring above this busy miniature world, exactly in the middle of the sky, a large bird seems to fly higher and higher. Is it an ordinary bird or the last memory of the presence of the Holy Ghost?

The creator of this landscape, Hendrick Avercamp (15891634), specialized in winter scenes. He painted them year-round in his workshops in Amsterdam and later in Kampen, in the Netherlands. Depicting bustling crowds socializing while apparently not feeling the cold may have been an expression of his own longing to be part of a greater world. He was born deaf and mute, lived quietly with his mother, and followed her into the grave within a few months of her death. The happy scenes he painted were always the lives of others.

Like all painters of his time, Avercamp created his compositions not from direct observation but from sketches and memory. Artists worked in their studios with paints that were freshly prepared, and it would have been a major technical challenge to transfer an entire studio outside. According to the ideas of the time, it would have seemed meaningless simply to paint what happened to be there. Not nature itself, but its symbolic meaning was of greater interest to artists and their patrons. A landscape was a skillful composition of disparate elements, not merely the documentation of reality. Avercamps sketches were assembled into a whole, an image of the social world in a deceptively natural settinganother reason why his landscapes consist of many individual scenes.

Detail, birds fly overhead.

Avercamp and his colleagues composed and constructed communities on the ice, creating an underlying sense that we must all share the same resources, we are all exposed to the same circumstancesa message characteristic of the Netherlands, where collective and cooperative work had been long established among farmers for maintaining dykes, draining marshes, and managing fishing. The aristocracy had never been strong here, and the convictions that everyone shared the same stretch of land and that people swim or sink together had deep roots in cultural practices and attitudes.

Next page