Imagining Xerxes

Bloomsbury Studies in Classical Reception

Bloomsbury Studies in Classical Reception presents scholarly monographs offering new and innovative research and debate to students and scholars in the reception of Classical Studies. Each volume will explore the appropriation, reconceptualization and recontextualization of various aspects of the Graeco-Roman world and its culture, looking at the impact of the ancient world on modernity. Research will also cover reception within antiquity, the theory and practice of translation, and reception theory.

Also available in the Series:

Ovids Myth of Pygmalion on Screen , Paula James

For my parents, with love and thanks

Imagining Xerxes: Ancient

Perspectives on a Persian King

Emma Bridges

Contents

Illustrations

Photographs

Translations are my own, unless otherwise stated. Translations of Persian inscriptions in (Routledge: London and New York 2007), and are reproduced by kind permission of the publisher.

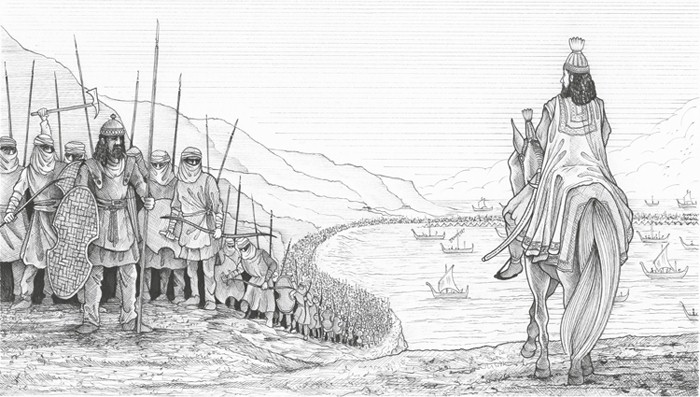

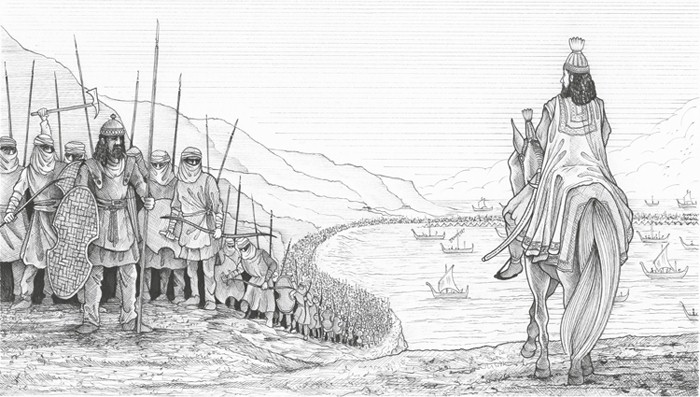

Chapter frontispieces were illustrated by Asa Taulbut. ) are reproduced courtesy of the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago.

Abbreviations of the names of ancient authors and texts follow those used in the Oxford Classical Dictionary . Standard abbreviations are used for modern texts. Persian inscriptions discussed in are referred to by the abbreviations used in Kent (1953) and Kuhrt (2007).

This book started life as a doctoral thesis written at the University of Durham and funded with the support of a Durham University Research Studentship and the Ralph Lindsay Scholarship. My doctoral supervisors, Edith Hall and Peter Rhodes, have continued to show their unfailing generosity in sharing their time and their wisdom, as well as in providing moral support and advice. I am especially grateful that both accepted and supported my decision to prioritize family life over academic pursuits for a time during the decade since the completion of the thesis, and yet unquestioningly resumed their roles as mentors when I was ready to take up the challenge of writing this volume. Ediths gentle yet firm encouragement inspired my decision to resume research; for this, and much else, it is no exaggeration to say that I will be forever in her debt. Both she and Peter offered comments on a complete draft of the finished work; as ever, I have benefited enormously from their combined expertise and their differing yet complementary approaches to the study of the ancient world.

The final version of the book has also been shaped along the way by the input of several other individuals and institutions. My examiners, Chris Pelling and Peter Heslin, offered invaluable insights which led me to think about the material in new ways; Chris has since then been a continuing source of support, and provided incisive comments upon without this invaluable facility in Yorkshire the pursuit of my research would undoubtedly have been far more difficult and drawn-out. In the final stages of the writing process Asa Taulbut offered up his time and his remarkable talent to produce the illustrations at very short notice; I valued greatly the opportunity to share ideas with him as well as his capacity to create beautiful visual representations of those ideas.

Several others also deserve credit for their role in developing more broadly my own ability and self-confidence as a classical scholar. The roots of my enthusiasm for the classical world were first planted by Ken Parham of Durham Sixth Form Centre and later nurtured at Brasenose College, Oxford, by Ed Bispham, Llewelyn Morgan, the late Leighton Reynolds, and Greg Woolf. I am indebted to each of them for their encouragement and their faith in me, and can only hope that the present work proves that faith to have been justified.

That this volume has eventually come to fruition is due in no small part to the love and understanding of my family, whose presence is my anchor. My husband David has wholeheartedly supported the project; along with our children, Charlotte and Joseph, he has patiently endured my preoccupation with Xerxes for the past year. My parents, Margaret and Terry Clough, provided the foundation upon which all that I have achieved has been built. As always, they have been an unfailing source of support both emotional and practical throughout this process yet, with their customary kindness and modesty, expect nothing in return. It is to them that this book is gratefully dedicated.

Their struggle against Xerxes was not the mainland Greeks first encounter with a mighty Asiatic foe; ten years previously, the Athenians and their Plataean allies had secured at Marathon a decisive victory over the Persian force sent to Greece by Xerxes father Darius. Yet, where Xerxes set foot on the Hellenic soil which he intended to claim as his own and in the course of his expedition committed the ultimate act of desecration in burning the sacred buildings of Athens Darius had remained in Persia and instead sent his generals to carry out his campaign. As a result it was Xerxes, not his father, who subsequently entered into the Greek cultural encyclopaedia both as the archetypal destructive and enslaving eastern king and as a symbol of the exotic decadence, wealth and power of the Persian court. The narratives of his exploits are rich in motifs and episodes with which he came to be associated: the whipping and branding of the sacred Hellespont which mirrored both his mission as would-be enslaver and his brutal treatment of subordinates; his awe-inspiring army which was said to have drunk dry the rivers on its journey to Greece; the elaborate throne from which he observed his troops in battle; and the sexual politics of his palace, to name a few. The king himself, whose defeat at Salamis would be for the Greeks a lasting cause for celebration, was a figure who could inspire both fear and hatred, and whose image would at the same time become a source of enduring fascination in a literary tradition whose echoes would continue to resonate for centuries. The central concern of this volume is to explore the richness and variety of Xerxes afterlives within the ancient literary tradition.

The historical encounter between Xerxes and the Greeks has been the focus for several recent scholarly endeavours, with attention being paid to particular texts While the process of disentangling the ancient testimonies in order to establish a narrative of Xerxes reign and his invasion of his Greece is a rich field for study, however, my concern here is not to produce a biographical account or a cohesive picture of the real historical king who spearheaded the second Persian invasion of Greece. Instead it is to draw together for comparative analysis the range of literary approaches to the figure of this king with a view to considering the ways in which these adaptations and deformations of the Xerxes-traditions from the earliest appearance of Xerxes on the tragic stage in 472 BC and the portrayal of his character in Herodotus fifth-century historiographical narrative to the biographical works of the Roman tradition and the moralizing texts of the Second Sophistic were shaped by the diverse contexts within which they were produced. These successive re-imaginings from a variety of cultural and historical perspectives demonstrate that the figure of the king who played such a key role in events of the fifth century BC inspired an astonishing array of responses; in this sense the real historical Xerxes has become inseparable from the literary character(s) who developed in his wake.