All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be

reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic

or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information

storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented without

permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who

wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review written

for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast.

This is the setting-forth of the research [histori] of Herodotus of Halicarnassus, done so that the achievements of men may not be lost to memory over time, and that the great and wondrous deeds of both Greeks and barbarians [non-Greeks] may not lack their due glory; and especially to show what was the cause why the two peoples fought against one another.

Herodotus Histories 1.1

S HORTLY AFTER finishing my last book on Alexander III the Great King of Macedon (and a great deal more besides) between 336 and 323 BC(E) I paid a visit to Thermopylae in preparation for writing this one. From plotting the world-changing course of Alexander the Great over most of the known world to charting the history-changing defence of a narrow pass by a Few. The task was similar in many ways the weighing of evidence, the estimation of consequence and implication, the judgement of value but here the subject, though comparably massive, is concentrated in one act carried out in a little space: a suicidally defining stand for freedom.

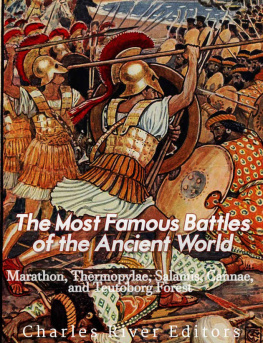

The Hot Gates that is what Thermopylae means in ancient Greek are a narrow pass in north-central mainland Greece. The gates bit referred to the fact that this was the natural and obvious route for any invading army coming from the north to defeat the forces of central or southern Greece. They were called hot because of the presence nearby of natural healing sulphur springs still there today. Here it was that in August 480 BCE an ancient Greek Few, representing a small and wavering grouping of Greek cities, made their heroic stand against the oncoming might of a massive Persian invasionary force. They were headed by an elite force from Sparta, the single most powerful Greek polis, or citizen-state.

It is disconcerting to find that today the National Road linking Athens with Greeces second city, Thessaloniki in Macedonia, carves its way slap bang through this deeply historic site. Imaginative reconstruction of the ancient scene is not much helped, either, by the occurrence of key changes in the geomorphology of the region. Since the fifth century BCE there have been at least two major earthquakes, and besides those the River Spercheius has laid down alluvial deposits that have caused the sea to recede some five kilometres to the north. So that what was once a narrow (2030 metres wide) mountain defile with the sea roaring close by on one side has become a road through a fairly broad coastal plateau, with the sound of the sea but a distantly gentle murmur (when, that is, the roar of the trucks and other motor traffic hurtling by does not drown it out).

The modern memorials to Leonidas and the other Greeks killed here in desperate battle in 480 BCE were first erected beside the National Road in the mid-1950s by the Greek government with the aid of American money. This was not all that long after a devastating civil war (19469) had left at least half a million Greeks dead. This intestine conflict in its turn had followed hotly on a period of deeply unpleasant foreign occupation by the Axis powers of first Italy and then Nazi Germany (19414), notwithstanding the heroic Greek resistance in late 1940 that prompted comparison precisely with their ancestors derring-do of 480 BCE .

Clearly, the soothing balm of a memorial to men who had famously given their lives resisting a foreign invasion and an attempted conquest was then sorely needed. The monuments, which have been added to since the mid-1950s, are indeed still suitably powerful and evocative. But if you cross to the other side of the National Road, the rewards for the student of 480 BCE are even greater. Close by is what has been identified almost certainly correctly as the low hill on which the Spartan King Leonidas and his few Spartans mounted their heroic last stand against Great King Xerxess Persians. If you search among the scrub that overlies the site, you will come upon another modern memorial, this one set flat into the ground and decorated appropriately with green Laconian stone (Lapis lacedaemonius) from an area south of Sparta. This memorial is poetic in a literal as well as a metaphorical sense: inscribed upon it is a copy of the two-line epigram, an elegiac couplet, composed twenty-five centuries ago by the contemporary praise-singer Simonides son of Leoprepes from the island of Ceos. This reads, in its most usual English translation:

Go tell the Spartans, passerby,

That here, obedient to their laws, we lie.

Obedience and freedom, self-sacrificing suicide Thermopylae is a place of witness, redolent of the Spartans paradoxical cultural values that need explaining now as much as at the time, when Persian Great King Xerxes uncomprehendingly wondered at the report of these fearsome warriors combing their hair in preparation (though he did not know it) for a beautiful death.

In Alexander the Great: The Hunt for a New Past I considered the final act in one of the greatest dramas in Middle Eastern history: the conquest by Alexander of the once mighty Achaemenid Persian Empire, founded by Cyrus II, also the Great, in about 550. In this book I am going back a century and a half and looking at that empire when it was at or near its peak, in terms of expressible and visible power wielded from its historic centre in Iran. In 334 Alexander invaded the Asiatic Persian Empire from the European west, from northern Greece. In 480 Great King Xerxes of Persia invaded Europe that is, Greece at pretty much the same point but from the east. In the very broadest historical perspective of all it is indeed the cultural East versus West dimension of the conflict that obtrudes. This is as it should be. Herodotus, our first and best historian of what I shall call the Graeco-Persian Wars, saw things this way himself (see the epigraph on p. ix), and it is in his balanced footsteps that I seek very distantly to tread.

Moreover, this clash between the Spartans and other Greeks, on one side, and the Persian horde (including Greeks), on the other, was a clash between Freedom and Slavery, and was perceived as such by the Greeks both at the time and subsequently. In fact, the conflict has been plausibly described as the very axis of world history. The interest of the whole worlds history hung trembling in the balance, so the world-historically minded nineteenth-century German theoretician Hegel powerfully put it. At stake were nothing less than early forms of monotheism, the notion of a global state, democracy and totalitarianism. The Battle of Thermopylae, in short, was a turning-point not only in the history of Classical Greece, but in all the worlds history, eastern as well as western.