FOR FREEDOM ALONE

This eBook edition published in 2013 by

Birlinn Limited

West Newington House

Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

First published in 2003 by Tuckwell Press, East Linton

This edition first published in 2008 by Birlinn Ltd

Copyright 2003, 2008 Edward J. Cowan

The moral right of Edward J. Cowan to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in an information retrieval system now known or yet to be invented, or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical or electrical, photocopied or recorded without the express written permission of the publishers except by a reviewer wishing to quote brief passages in a review either written or broadcast.

eBook ISBN: 978-0-85790-670-0

ISBN: 978-1-84158-632-8

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

LIST OF PLATES

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The Declaration of Arbroath, as it has come to be known, is one of the most remarkable documents to have been produced in late medieval Scotland. Quoted by many, understood by few, its historical significance has now almost been overtaken by its mythic status. The beginning of a new century, in the wake of the re-establishent of the Scottish Parliament, seems an appropriate moment to re-examine one of Scotlands long-cherished historical icons.

My indebtedness to various historians will be obvious in the following pages. Of those who have illuminated the study of Arbroath (as I refer to it when I intend to signify the document rather than the burgh) I am greatly beholden to Professor Archie Duncan, particularly for permission to include his translation of Arbroath, and to Professor Geoffrey Barrow. The late Professor Ranald Nicholson first introduced me to the subject many years ago. North American interest in the Arbroath Declaration served to rekindle my own. In this respect I must thank Bill Somerville of Toronto, sometime president of the Scottish Studies Foundation, Dave Pritchard of Visualize Productions, Alison Duncan of Washington DC, Alan Bain of the American Scottish Foundation and Duncan Bruce of New York. Colin Kidd kindly commented on the typescript, saving me from several errors, though those that remain are my responsibility alone. John and Val Tuckwell proved, as ever, patient and sympathetic publishers. My greatest debt is to Lizanne, who made many helpful comments on the first draft and who frequently rescued me when my computer decided to embark upon a freedom quest of its own, refusing to submit to external domination.

E. J. C.

Glasgow, 1 October 2002

A Note on the Text

The reviewers were generally kind to the first edition of this book though I remain uncertain that all of them, together with certain other media pundits, actually read it. This edition corrects a number of errors and typos while incorporating some recent research, notably that which appeared in Geoffrey Barrow (ed.) The Declaration ofArbroath: History, Significance, Setting, Edinburgh 2003, the proceedings of a conference held in Arbroath on 20 October 2000 and organised by the Society of Antiquaries, Historic Scotland and Angus Council. I have particularly profited from the contributions of Dauvit Broun, The Declaration of Arbroath: Pedigree of a Nation?, and Archie Duncan, The Declarations of the Clergy, 130910. New or additional material in the present edition includes some discussion of Duns Scotus possible contribution to evolving Scottish political ideas, based upon the work of Professor Alexander Broadie and Fr Bill Russell, both of whom have kindly shared their findings with me. Also included is an explanation as to why the Arbroath Declaration was dated 6 April. The commemorations of the seven-hundredth anniversaries of the execution of William Wallace and Robert Bruces inauguration as King of Scots, in 2005 and 2006, respectively, prompted some fresh ideas on both of these remarkable individuals. There is further discussion of the role of the Arbroath folk in the popularisation and mythologisation of their Declaration, as well as a little more information on the origins and development of Tartan Day, more fully discussed in my Tartan Day in America in Transatlantic Scots, Celeste Ray, ed. (2005). Appendix 2 reproduces Printed Versions of the Declaration of Arbroath, which first appeared in my Declaring Arbroath in Arbroath, Barrow, ed. (2003).

I am grateful to John and Val Tuckwell, Hugh Andrew and Andrew Simmons for their patience and support. As ever, Lizannes efforts to modify some of my dafter notions are appreciated even more than her superior computer skills.

Global interest in the Arbroath Declaration continues to grow. The document must, of course, be viewed in its own context and of its own time, but there is no doubt that it remains inspirational in its invocation of the universal ideas of constitutionalism and freedom. How it came to be is the theme of this modest book.

E.J.C.

University of Glasgow at Dumfries

Crichton Campus

Dumfries

25 March 2008

1

A Letter from Arbroath

There is still much to be learned from that remarkable manifesto. Read it again, and judge for yourselves whether it does not deserve on its merits to be ranked as one of the masterpieces of political rhetoric of all time.

LORD COOPER (1951)

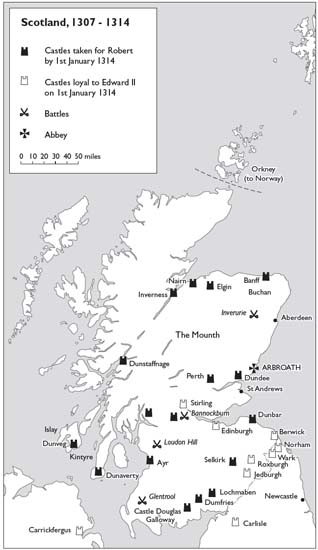

Arbroath is a burgh that feels as if it has always been there, nowadays retreating up the hill from its harbour, split by the coast road from Dundee to Aberdeen, but still dominated by the ruins of the abbey founded by William the Lion, king of Scots, in 1178. Down in the old town, by the harbour, the air reeks of the pungent, delectable mouthwatering odour of smokies: haddocks cured over oak chips. Since 1947 the Arbroath Pageant has celebrated the most famous event in the burghs history, which, in the best traditions of historical commemoration, never actually happened. From there a letter to the pope was dated on April 6, 1320, which originated, not in a crowded parliament or convention, but rather in the comparative obscurity of the royal chancery located somewhere in the abbey. Written in the high-flown style which papal correspondence demanded, the Declaration of Arbroath, as it is known, has, over a period of almost 700 years, acquired a near-mythic status as it has come to be regarded as inextricably linked to Scottish identity and nationalism. The letter is real enough. It survives and it can be read and has now been translated several times from its original Latin into English, and into metrical Gaelic and Scots; it belongs to Arbroath as well as the world. But there was no gathering at Arbroath in 1320, no great ceremony at which the glitterati of Scotland stepped forward with trembling hands to sign a document which they somehow were aware would be known in future years as a type of early Scottish constitution, as a ringing endorsement of Scottish nationalism, past and present, and as the supreme articulation of Scottish identity and the immortal values for which all Scots were allegedly willing to lay down their lives. The National Trust for Scotland, for example, self-appointed keeper of the nations soul, in depicting the Scottish nobility armed to the teeth and attacking the document with a quill pen, in its Bannockburn exhibit, is guilty of historical amnesia, bogus distortion and heritage creationism.

Next page