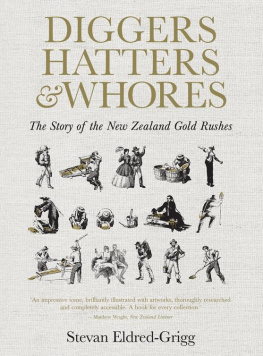

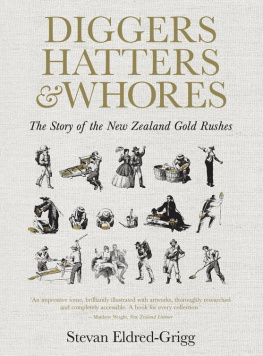

It opens with a survey of worldwide rushes, when for the first time in history a vast army of gold diggers began to revolve from continent to continent. It then looks at rushes throughout the country Coromandel, Golden Bay, Otago, Marlborough, the West Coast and Thames. In addition various themes of the rushes are examined thematically. Diggers, Hatters & Whores is both a wonderful read and a pleasure to look at.

Simply the best and most lively overall historical account I have yet come across of the worlds great gold rushes written in a forthright and racy style.

The best account we have yet of our 19th-century gold rushes capacious, lavishly illustrated and lively.

Big, rollicking sweat, scandal, sex and money.

A tour de force immensely readable, an important work.

A perfect exodus

Gold, Gold, Gold, is the universal subject of conversation, cried a newspaper. The gold fever is running to such a height that, if it continues, there will be scarcely a man left in town.

Otago, in the colony of New Zealand, was the province gripped by that fever. The year was 1861. Society seemed unhinged. Waggons had begun to creak, horses to snort, and booted men and boys to tramp towards a hinterland unknown to almost all. Clerks dropped their Not only had a gold rush broken out, a watershed had suddenly been stumbled across in colonial history.

Yet this was by no means the first news of gold in New Zealand. Nuggets had been found for years. Eighteen years before gold madness gripped Otago, a surveyor had picked one up in the bed of the Aorere River in the province of Nelson. The river had not been rushed.

No one, commented a writer a generation later, ever thought of or believed in gold fields.

Nor had finds in other rivers led to a rush. Nobody anywhere in the colony dreamt of hurrying to faraway valleys to dig for gold. Nor did anybody in the four nearby colonies of Van Diemens Land, New South Wales, South Australia and Western Australia. Nobody almost anywhere in the world had heard, yet, that there could be such a thing as a gold rush.

Gold rushes, as far as we know, are something new in history. They seem not to have happened in the history of India, China, the Middle East or Africa. They belong to the West. Gold fever began and grew with the beginnings and growth of capitalism, a thrusting new way of handling men and women and things. It first took root in Europe, and with the years it drove more and more Europeans across the oceans and around the globe looking for more and more ways to make money.

The first land in history known to have come down with gold fever was a sugar colony.

General Mines

Brazil at the end of the seventeenth century was a colony of Portugal. White landowners with their black slaves grew sugar along the tropical coast. Traders, scattered more thinly, had begun working their way into the wooded savannahs of the hinterland. Very slowly, news spread by word of mouth that some of those traders had found gold. Brazil, lacking newspapers and roads, was far from an advanced economy. Yet the colonists were stirred by the news, and their stirrings were clearly linked with the boom and bust cycles of worldwide capitalism. Sugar, formerly the sweet source of economic sustenance, was in a slump. Planters, merchants, brigands, cattle herders, slave raiders and runaway slaves began trudging overland to the goldfields soon to be known as Minas Gerais, meaning General Mines. News blew across the ocean to Portugal. Men and boys thronged so thickly onto the wharves of Lisbon that not enough ships could be found to carry them to the colony.

Minas Gerais within only a few seasons yielded more gold than had been dug anywhere in the world for whole centuries, with output peaking at about 14,000 kilograms annually.

The rush in Brazil had many of the hallmarks of later rushes. Men and women on the goldfields worked hard and drank hard. They were often willing to shrug off the law. They were restless. Word would come of some supposedly richer diggings elsewhere and everyone would ditch their claims in the wink of Claimholders quarrelled with one another angrily about ownership of claims, boundaries of claims, and rights to water wanted for washing gold from claims. They quarrelled as angrily with the state, which held that gold found in the ground was the property of the king. Licences and taxes were the way that right was asserted, and it led to open rebellion.

The hunt for gold in colonial Brazil was, however, in other ways very unlike the rushes of the nineteenth century. One key difference was that work was done by slaves. Not all were bondsmen a few thousand black or mulatto faiscadores dug as free workers but diggers overall were unwilling workers kept to their task by the wielding of whips. Another key difference was that the Portuguese empire in the eighteenth century lacked the wealth and technology that would pump the pistons of rushes in the nineteenth century. Money and manpower were stretched so thinly that digging for gold meant stripping towns of their trade and leaving farms to grow weeds not crops. The rushes of the nineteenth century, by contrast, would lead almost overnight to a swift intensification of urban commerce and cash farming near the diggings.

Also unlike later rushes was the way the diggings were not hyped. Indeed, the state kept them shrouded in secrecy. Cultura e Opulncia do Brasil, a book published in 1711 about the wealth of the goldfield, was ordered burnt by Joo V of Portugal. Travellers who tried to visit the diggings without written permission from the crown were condemned to slavery. Vila Rica rose, glittered, tarnished and fell without anything other than hearsay finding its way outside Brazil and Portugal.

Nor was much more of a ripple made in the world by the next big rush, well over a century later, when new finds sent throngs of hopeful diggers hurrying into the shallow, lonely valleys of Siberia.

Green and gold in the taiga

Siberia was an immense colony of imperial Russia. Steppes stretched eastwards until they stopped at the taiga, one of the greatest forests in the world. Taiga summers were dry and hot, winters bitterly cold. Swaying, whispering swathes of larch and spruce, fir and pine, drove roots down into permafrost.

Tribal societies had been living lightly in the taiga for thousands of years. Cossacks, merchants, soldiers and settlers began working their way eastwards from the seventeenth century. Money was made by skinning ermines, sables and foxes. A waning of the fur trade in the eighteenth century led the imperial state and some merchants and holders of land grants to turn to mining as a way of making good their investments in Siberia. Silver, lead and copper began to be dug. Gold was dug too. A breakthrough came in the late 1830s when rich troves were found in the shingle riverbeds of the Yenisei. A rush set in from other reaches of Russia. Yields peaked at about 21,000 kilograms yearly.

Gold belonged to the state, which granted mining concessions to moneyed men who in turn leased the grants to contractors. Diggers, often criminal or political exiles, were fed, housed, paid a wage and allowed the right to form their own bands under their own elected leader. Whipping of diggers was disallowed by law. Diggers drank. Bosses drank too. A raging ocean of vodka was poured down the throats of the workmen, wrote a German observer, while inexhaustible springs of champagne were swilled by their masters.