THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK

PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

Copyright 2012 by Andrea Wulf

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

www.aaknopf.com

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Wulf, Andrea.

Chasing Venus : the race to measure the heavens / Andrea Wulf.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-0-307-70017-9 (hardback)ISBN 978-0-307-95861-7 (ebook)

1.Geodetic astronomyHistory18th century.2.AstronomyHistory18th century.3.Venus (Planet)Transit.I.Title.

QB205.A2W85 2012

523.92dc23 2011049136

Cover design by Gabriele Wilson

v3.1

To Regan

The planet Venus drawn from her seclusion, modestly delineating on the sun, without disguise, her real magnitude, whilst her disc, at other times SO lovely, is here obscured in melancholy gloom.

Jeremiah Horrocks

We must show that we are better, and that science has done more to humankind than divine or sufficient grace.

Denis Diderot

Contents

1

Call to Action

2

The French Are First

3

Britain Enters the Race

4

To Siberia

5

Getting Ready for Venus

6

Day of Transit, 6 June 1761

7

How Far to the Sun?

8

A Second Chance

9

Russia Enters the Race

10

The Most Daring Voyage of All

11

Scandinavia or the Land of the Midnight Sun

12

The North American Continent

13

Racing to the Four Corners of the Globe

14

Day of Transit, 3 June 1769

15

After the Transit

Authors Note

In the interests of clarity and consistency I have retained in the maps and in the text certain place names of the viewing stations as the transit astronomers referred to them in the eighteenth century. Instead of the modern Puducherry, for example, I have used Pondicherry; Bencoolen instead of Bengkulu; Madras instead of Chennai; Constantinople instead of Istanbul. In some rare cases where the old names have fallen completely out of use, I have taken the modern name: Jakarta instead of Batavia, for example. Please refer to the List of Observers for a full list of the historic and contemporary names.

Dramatis Personae

Transit 1761

Britain

Nevil Maskelyne: St Helena

Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon: Cape of Good Hope

France

Joseph-Nicolas Delisle: Acadmie des Sciences, Paris

Guillaume Le Gentil: Pondicherry, India

Alexandre-Gui Pingr: Rodrigues

Jean-Baptiste Chappe dAuteroche: Tobolsk, Siberia

Jrme Lalande: Acadmie des Sciences, Paris

Sweden

Pehr Wilhelm Wargentin: Royal Academy of Sciences, Stockholm

Anders Planman: Kajana, Finland

Russia

Mikhail Lomonosov: Imperial Academy of Sciences, St Petersburg

Franz Aepinus: Imperial Academy of Sciences, St Petersburg

America

John Winthrop: St Johns, Newfoundland

Transit 1769

Britain

Nevil Maskelyne: Royal Society, London

William Wales: Prince of Wales Fort, Hudson Bay

James Cook and Charles Green: Tahiti

Jeremiah Dixon: Hammerfest, Norway

William Bayley: North Cape, Norway

France

Guillaume Le Gentil: Pondicherry, India

Jean-Baptiste Chappe dAuteroche: Baja California, Mexico

Alexandre-Gui Pingr: Haiti

Jrme Lalande: Acadmie des Sciences, Paris

Sweden

Pehr Wilhelm Wargentin: Royal Academy of Sciences, Stockholm

Anders Planman: Kajana, Finland

Fredrik Mallet: Pello, Lapland

Russia

Catherine the Great: Imperial Academy of Sciences, St Petersburg

Georg Moritz Lowitz: Guryev, Russia

America

Benjamin Franklin: Royal Society, London

David Rittenhouse: American Philosophical Society, Norriton, Pennsylvania

John Winthrop: Cambridge, Massachusetts

Denmark

Maximilian Hell: Vard, Norway

Prologue

The Gauntlet

The Ancient Babylonians called her Ishtar, to the Greeks she was Aphrodite and to the Romans Venus goddess of love, fertility, and beauty. She is the brightest star in the night sky and visible even on a clear day. Some saw her as the harbinger of morning and evening, of new seasons or portentous times. She reigns as the Morning Star or the Bringer of Light for 260 days, and then disappears to rise again as the Evening Star and the Bringer of Dawn.

Venus has inspired people for centuries, but in the 1760s astronomers believed that the planet held the answer to one of the biggest questions in science she was the key to understanding the size of the solar system.

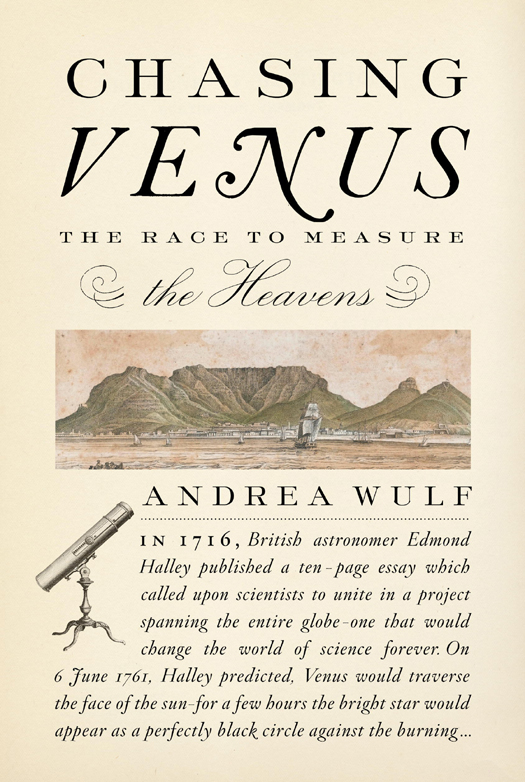

In 1716 British astronomer Edmond Halley published a ten-page essay which called upon scientists to unite in a project spanning the entire globe one that would change the world of science forever. On 6 June 1761, Halley predicted, Venus would traverse the face of the sun for a few hours the bright star would appear as a perfectly black circle. He believed that measuring the exact time and duration of this rare celestial encounter would provide the data that astronomers needed in order to calculate the distance between the earth and the sun.

The only problem was that the so-called transit of Venus is one of the rarest predictable astronomical events. Jeremiah Horrocks observed the event. The next pair would occur in 1761 and 1769 and then again in 1874 and 1882.

Halley was sixty years old when he wrote his essay and knew that he would not live to see the transit (unless he reached the age of 104), but he wanted to ensure that the next generation would be fully prepared. Writing in the journal of the Royal Society, the most important scientific institution in Britain, Halley explained exactly why the event was so important, what these young Astronomers had to do, and where they should view it. By choosing to write in Latin, the international language of science, he hoped to increase the chances of astronomers from across Europe acting upon his idea. The more people he reached, the greater the chance of success. It was essential, Halley explained, that several people at different locations across the globe should measure the rare heavenly rendezvous at the same time. It was not enough to see Venuss march from Europe alone; astronomers would have to travel to remote locations in both the northern and southern hemispheres to be as far apart as possible. And only if they combined these results the northern viewings being the counterpart to the southern observations could they achieve what had hitherto been almost unimaginable: a precise mathematical understanding of the dimensions of the solar system, the holy grail of astronomy.