The Day the World

Discovered the Sun

Copyright 2012 by Mark Kendall Anderson

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. For information, address Da Capo Press, 44 Farnsworth Street, 3rd Floor, Boston, MA 02110.

Designed by Timm Bryson

Set in 11.5 point Adobe Jenson Pro by The Perseus Books Group

Cataloging-in-Publication data for this book is available from the Library of Congress.

First Da Capo Press edition 2012

ISBN 978-0-306-82106-6 (e-book)

Published by Da Capo Press

A Member of the Perseus Books Group

www.dacapopress.com

Da Capo Press books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the U.S. by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 2300 Chestnut Street, Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA 19103, or call (800) 810-4145, ext. 5000, or e-mail .

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Penny

CONTENTS

I closed my lids, and kept them close,

And the balls like pulses beat;

For the sky and the sea, and the sea and the sky

Lay like a load on my weary eye,

And the dead were at my feet.

SAMUEL TAYLOR COLERIDGE

RIME OF THE ANCIENT MARINER

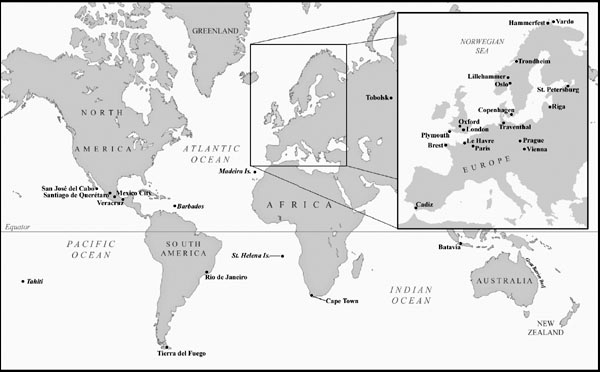

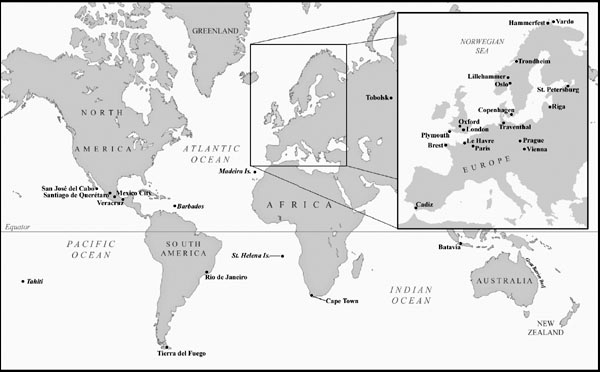

SAN JOS DEL CABO, BAJA PENINSULA

May 20, 1769

Oranges, bananas, pomegranates: how could such sweet fruit go so sour? Steady winds gusting off the Sea of Cortez did a fair job of keeping the flies from hovering over the dwindling piles of rotting food scattered around the huts and makeshift homes near the beach. But the flies had better places to lay their eggs. With every new day came a new crop of corpses.

Spanish frigate captain Salvador de Medina had spent nearly seven months escorting twenty-eight men across the Atlantic Ocean and the whole of Mexico to arrive at a former Jesuit sanctuary near the southern tip of the Baja peninsula. Medina had technically discharged his duty. But his orders included nothing about a deadly epidemic, a brutal and unforgiving fever sweeping through the local population and filling graves by the hour. Medina knew the epidemic posed too great a threat to risk staying.

Yet, the man at the center of the expedition, the French astronomer Jean-Baptiste Chappe dAuteroche, held his ground. Chappe, as he was known, had already begun to size up an abandoned corn barn at the former Jesuit mission inland. The barn would make a fine observatory, Chappe surmised. As if consumed by a fever of its own peculiar nature, Chappe refused to hear anything more about a port eighteen miles to the southwest. Word on the ground may have been that Cabo San Lucas was free of the contagion. But Chappe told Medina that he would not risk the expeditions founding purpose simply because of some rumor.

The groups late arrival on the white sandy shores of San Jos del Cabo the night before had left precious little time to spare before the afternoon sky would host a sensational spectacle.

The universe, Chappe liked to explain to anyone who would listen, would soon be opening itself up for a rare inspection. Although anyone without a telescope would never notice it, for five and a half hours on June 3, 1769, a little dot would appear to cross the disk of the sun. That little dot was the planet Venus. Its shadow crawled across the suns face, at most, only twice per century. Timing the planets entire transit down to the second and comparing other observations of the same event from elsewhere on the globe, Chappe said, would by years end enable humankind to discover something that had evaded it since the dawn of timethe exact physical dimensions of the sun and its planets and the distances that separated them. Venuss transit opened a brief window into the very architecture of Gods creation.

This, Chappe explained, is why no mere disease could be allowed to interrupt his careful observations of the practically theological phenomenon that a fortnight later would be taking place overhead.

Having spent his first night ashore sleeping on the beach, Chappe mustered what remained of the able-bodied natives. Two leagues inland stood the mission that would serve as Chappes observatory. Much work remained to be done, and with very little time to spare. The first job entailed hauling Chappes delicate telescope and other scientific equipment inlandprecision instruments whose every fragile inch had endured muttered curses of Spanish soldiers porting them nearly halfway across the world from ship to jungle and back to ship again.

The observatorys one widely recognizable instrument looked like the guts of a clock quartered and served up like a piece of pie. A kind of maritime priesthood wielded the quadrant with incantations and scriptures that were as mysterious as Holy Writ to most of the sailors.

A ships navigator typically used this machine and a table of nautical charts to measure the moon and sun and sometimes stars. Through a mathematical ritual that occupied the navigator for hours on end, these measurements would then produce a crucial number that everyone at sea could appreciate: longitude.

Longitude was the most costly puzzle of its time. And astronomy was poised to solve it. Esteemed astronomers like Chappe commanded authority with royal audiences and military commanders. Commanders like Medina.

The groans of wretched men and glimpses of the cadavers they became underscored how dire the situation had become. Still, as the mornings sweat turned clammy from cooler breezes that nudged the mule train inland, Medina and Chappe remained tense allies bound by deaths encroaching shadow.

Theirs was a world inching closer to discovering great secrets behind the sky. But the sun shone down relentlessly, and it forgave no one unprepared. The sun would have its day.

VIENNA, AUSTRIA

December 31, 1760

Reddened hands fastened the barge to its mooring. For the past month the Danubes breezes had chilled its travelers. No more. A brisk walk from the canal bank, and Viennawith its famously narrow streets, tall buildings, and fragrant coffeehouseswelcomed its visitors in from the cold.

Just eight years before he would travel to San Jos del Cabo, French astronomer Jean-Baptiste Chappe dAuteroche and his party made a wintry landing in the capital city of the Habsburg monarchy and, with it, much of the Holy Roman Empire. His was a journey altogether of its time. The turbulent 1760swhen the Enlightenment was in full bloom but before bloody revolutions had brought the ages heady ideals down to earthwould effectively frame the worlds most concerted effort to find the sun.

In transit from Paris, Chappe and his servantsas well as M. Durieul, a Polish military man traveling to Warsawoffloaded their Danube barge and walked through the city gates of Vienna. The crunching snow underfoot and clouds of condensed breath had become familiar companions as Chappes party daily pressed eastward. Still, the Viennese chill could not compare to the core-consuming freeze Chappe and his servants were about to undergo. Their ultimate destination was Tobolsk, a remote town in Siberia.