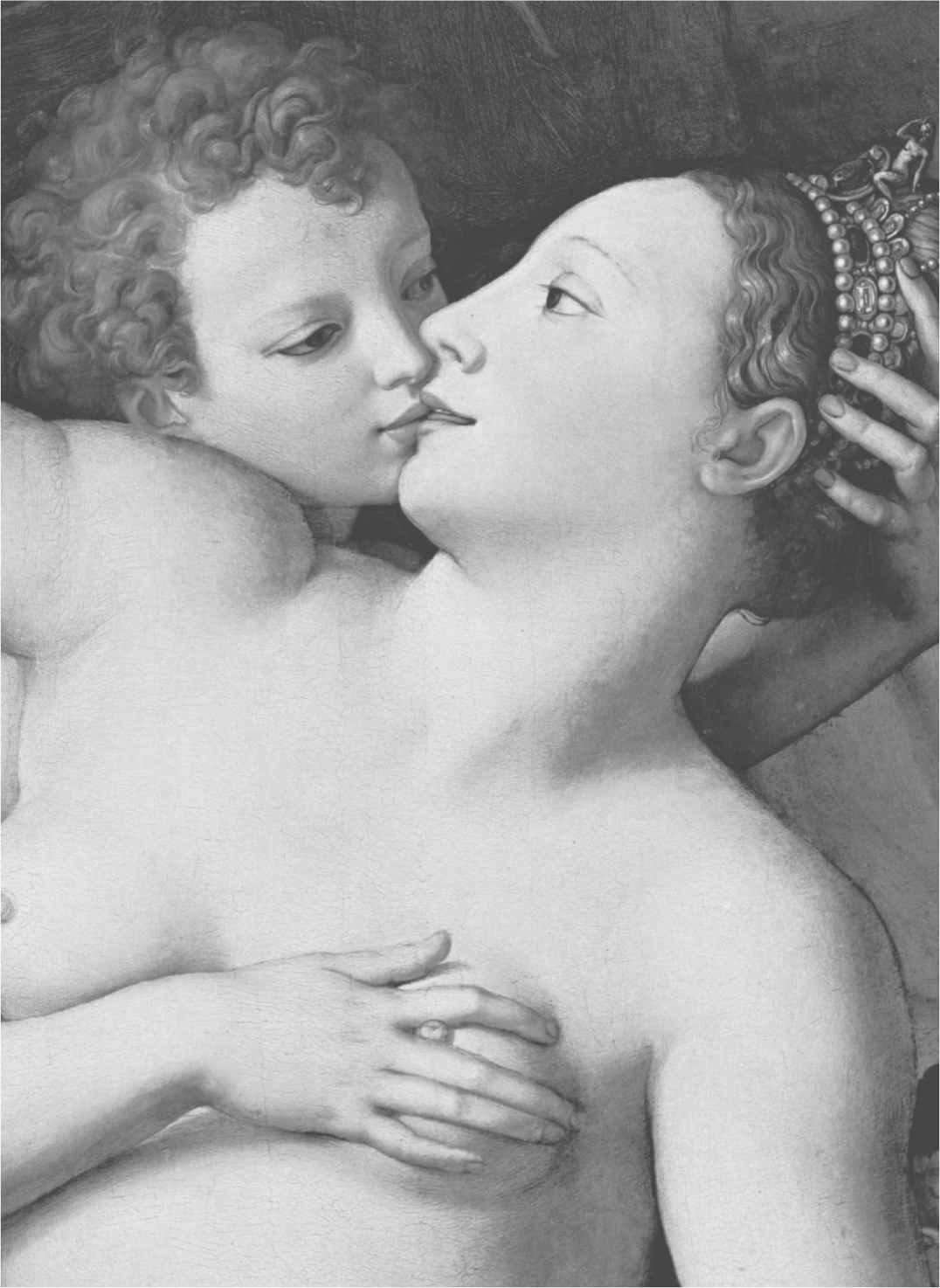

Bronzino, 154050, detail of An Allegory with Venus and Cupid (also called Venus, Cupid, Folly and Time), oil on wood

Contents

She spoke, and as she turned, her neck

Shone with roselight. An immortal fragrance

From her ambrosial locks perfumed the air,

Her robes flowed down to cover her feet,

And every step revealed her divinity.

And then she was gone, aloft to Paphos,

Happy to see her temple again, where Arabian

Incense curls up from one hundred altars

And fresh wreaths of flowers sweeten the air.

Virgil, The Aeneid , 1.494514, trans. Lombardo

In the high-security storeroom in the heart of the ancient site of Pompeii a pair of beady, dark eyes stare out from the metal shelves. They belong to a foot-or-so-high limestone statuette of the goddess Venus.

The degree of survival is remarkable. Not only has Venus been left with full, glass-eyed sight (in spite of the massive volcanic eruption of Vesuvius in AD 79 which, at its most ferocious, threw 100,000 tonnes of magma per second into the air), but she is flushed with colour. Venus hair is golden; her drapery, pink-blushed, tumbles off around her hips, skimming, but still revealing, her sex.

This is the Venus we think we know. Safe, attractive, chocolate-box-pretty. But the goddess of sexual love is in fact a far richer and more complicated creature than she at first appears. A potent idea, given a name and a face across five millennia, this deity is the incarnation of fear as well as love, of pain as well as pleasure, of the agony and ecstasy of desire. Venus is in fact the summation of the variegated, complicated business of human-heartedness of our burning drive to engage with one another, both for good and for bad. She oversees the intensity of our passions and of our relationships within, and beyond, our species.

So, like the humans whose form she sometimes inhabited, the goddess of love has a richly complicated, tantalising, tricky, surprising and sensuous life story. For four decades I have followed the scent of her trail. It is a journey that has taken me to archaeological digs in the Middle East and archives in the chill of the Baltic; from the shores of the Caspian Sea to the nightclubs of Hoxton. Here is what I have found, an evolving history of the goddess of many kinds of love.

Rising up from her mother the sea. Look,

The Cyprian, she whom Apelles laboured hard to paint!

How she takes hold of her tresses

Damp from the sea! How she wrings out the foam

From these wet locks of hers! Now Athene and Hera

Will say

In beauty we can never compete!

Things do not start well.

Venus or Aphrodite as she was originally called by the Greeks was a primordial creature, said to have been born out of an endless black night before the beginning of the world.

Ancient Greek poets and myth-makers told this ghastly story of her origins. The earth goddess Gaia, sick of her eternal, joyless copulating with her husband-son, the sky god Ouranos (sex which left Gaia permanently pregnant, their children trapped inside her), persuaded one of her other sons, Kronos, to take action. Gathering up a serrated flint sickle, Kronos frantically hacked off his fathers erect, rutting penis and threw the dismembered phallus and testicles into the sea. As the bloody organs hit the water, a boiling foam started to seethe. And then something magical happened. From the frothing sea-spume rose an awful and lovely maiden, the goddess Aphrodite. This broiling, gory mass proceeded to travel the Mediterranean, from the island of Kythera to the port of Paphos in Cyprus.

But despite her violent and salty start, the young goddess, as she emerged from the sea on to the barren, dry land, witnessed a miracle: green shoots and flowers springing up beneath her feet. The radiant, enigmatic creature, followed by comely desire, was quite a sight to behold:

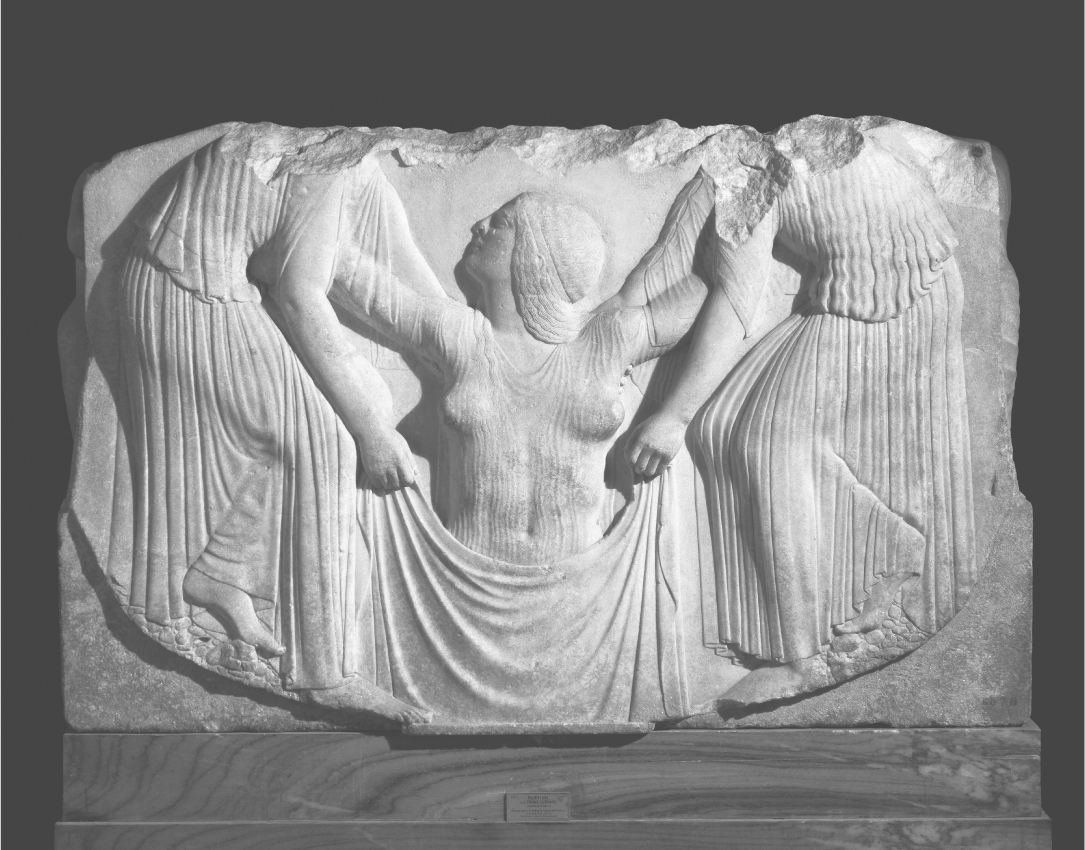

Aphrodite, assisted by two Horai goddesses representing the seasons emerges from the sea on the Ludovisi Throne. This relief was almost certainly originally made c .480 BC for a temple in Locri, in modern-day Calabria

She set on her skin the garments which the Graces and the Seasons had made and dyed in the flowers of spring-time, garments such as the Seasons wear, dyed in crocus and hyacinth and in the blooming violet and in the fair flower of the rose, sweet and fragrant, and in ambrosial flowers of the narcissus and lily.

Aphrodite, an incarnation of fecund life, was accompanied, as she made her flower-sweet progress through the dusty earth, by gold-veiled Horai, the two Greek seasons of summer and winter, spirits of time and of good order. Born from abuse and suffering, this sublime force is being described to us not just as the goddess of mortal love, but as the deity of both the cycle of life and life itself. Aphrodite is far more than an attractive figure on a Valentines Day card.

This is how many in Ancient Greece explained Aphrodites birth. It is a story, with some variations (an alternate myth suggested that Aphrodite was the daughter of the king of the gods, Zeus, and the sea-nymph Dione), that was told and retold across the Mediterranean world. The ancients had a vivid mental picture of how their supernatural goddess of love and desire was conceived. Her psychological imprint was evident. But what about her physical trail? What does the archaeology in the ground reveal about the historical inception of Aphrodite and of her adoration?

As we might expect, the material evidence offers a compelling alternative to the myth. Yet the truth of Aphrodites origins is almost as strange as the fiction.

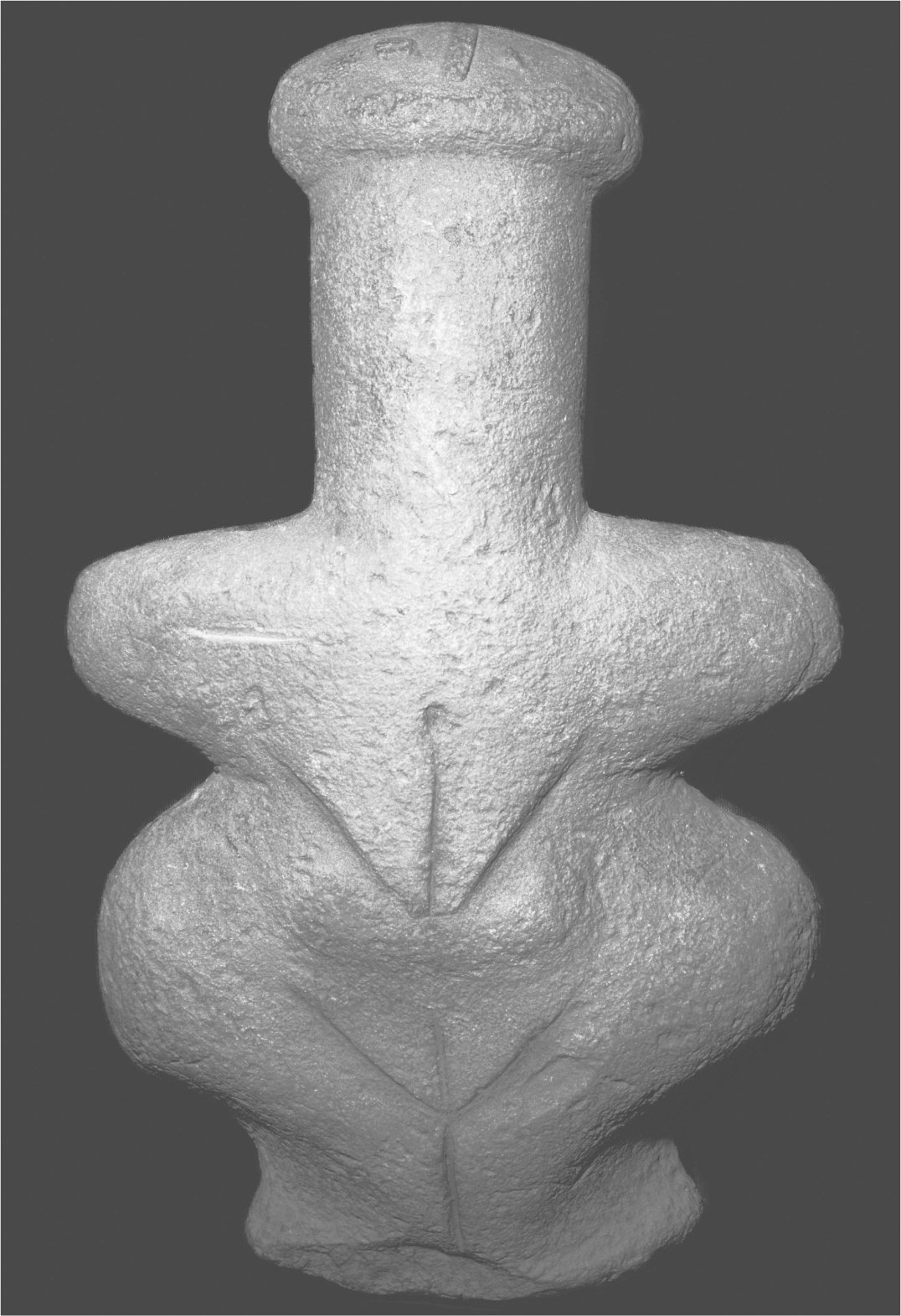

On the island of Cyprus there is a record of the celebration of the miracle of life, and of the sexual act, long before the Classical Greeks conceived of a voluptuous blonde they named Aphrodite. The life-giving powers of a spiritual, highly sexualised figure can be found in the formidable form of the so-called Lady of Lemba , a quite extraordinary limestone sculpture. Over 5,000 years old, this wonderful creature has fat, fructuous thighs, a pronounced vulva, the curve of breasts and a pregnant belly and instead of a neck and head, a phallus, with eyes. The Lady of Lemba is in fact a wondrous mix of both female and male. I have had the privilege of studying this Lady outside her glass case. Thirty centimetres tall, she pulses with power and potential. Found lying on her back, surrounded by other, smaller figurines, the Lady of Lemba is intriguing, a distant ancestor of our goddess of love. And shes not alone.

The Lady of Lemba , Cyprus, c. 3000 BC , detailing both a phallus / phallus neck and a vulva. Found at the site of Lemba in 1976

Probing deeper in time, back at least 6,000 years, the plateaux and foothills of western Cyprus are littered with tiny, pregnant stone-women, again with phallic-shaped necks and faces and pronounced female sex organs. These figurines lovely things, crouching down, smooth to touch, an otherworldly soft green were produced in huge numbers here. Many have pierced heads, so must have been worn as amulets. I first met these inter-sex marvels in the atmospheric back storerooms of the old Cyprus Museum in Nicosia. Lovingly laid in Edwardian wooden cabinets, they are an extraordinarily vivifying connection to a prehistoric past. A number of the figures, made of the soft stone picrolite, have shrunken versions of themselves worn, as amulets, around their own stone necks. Dating from a time the Copper Age when the division of labour between women and men on Cyprus seems to have had parity, the majority of the enigmatic taliswomen-men were found in domestic spaces or near what could be prehistoric birthing centres. (Those mini-mes around their necks may represent unborn children.) Some of the basic stone-and-mud huts at one site, Lemba, have now been reconstructed. Shaded by olive trees, the prehistoric maternity wards make for a curious, sidebar of interest as tourists petrol-past on their annual sea-and-sand holidays.