Published in 2019 by Britannica Educational Publishing (a trademark of Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc.) in association with The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc.

29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010

Copyright 2019 by Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc. Britannica, Encyclopdia Britannica, and the Thistle logo are registered trademarks of Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc. All rights reserved.

Rosen Publishing materials copyright 2019 The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc. All rights reserved.

Distributed exclusively by Rosen Publishing.

To see additional Britannica Educational Publishing titles, go to rosenpublishing.com.

Britannica Educational Publishing

J.E. Luebering: Executive Director, Core Editorial

Andrea R. Field: Managing Editor, Comptons by Britannica

Rosen Publishing

Nicholas Faulkner: Editor

Brian Garvey: Series Designer / Book Layout

Cindy Reiman: Photography Manager

Sherri Jackson: Photo Researcher

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Faulkner, Nicholas, editor. | Gregersen, Erik, editor.

Title: The inner planets / edited by Nicholas Faulkner and Erik Gregersen.

Description: New York : Britannica Educational Publishing, in Association with Rosen Educational Services, 2019 | Series: The universe and our place in it | Audience: Grades 7-12. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018011821| ISBN 9781508106098 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Inner planets--Juvenile literature. | Solar system--Juvenile literature.

Classification: LCC QB606 .I56 2018 | DDC 523.4--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018011821

Manufactured in the United States of America

Photo credits: Cover (top), p. 1 Carlos Fernandez/Moment/Getty Images; cover (bottom) Johan Swanepoel/Shutterstock.com; back cover iStockphoto.com/lvcandy; p. 7 NASA/Lunar and Planetary Institute; pp. 10, 24, 27, 29 NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Carnegie Institution of Washington; p. 14 NASA/TRACE/SMEX; p. 21 NASA/JHUAPL/Carnegie Institution of Washington/Science Source; pp. 26, 68 NASA; pp. 36, 59, 61 NASA/JPL; pp. 41, 48 NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center; p. 44 (top and bottom) Courtesy of C.M. Pieters through the Brown/Vernadsky Institute to Institute Agreement and the U.S.S.R. Academy of Sciences, and C.M. Pieters et al. The Color of the Surface of Venus, Science, vol. 234, p. 1382, Dec. 12, 1986,copyright 1986 by the American Association for the Advancement of Science; p. 46 Detlev van Ravenswaay/Science Source; p. 51 NASA/JPL/Caltech (NASA photo #PIA00311); p. 64 NASA/NOAA/GSFC/Suomi NPP/VIIRS/Norman Kuring; pp. 74, 76, 78, 81, 83, 93 Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc.; p. 91 NASA/JPL/Malin Space Science Systems; p. 96 NASA/JPL/Main Space Science Systems; p. 98 NASA/JPL-Caltech/Univ. of Arizona; p. 102 NASA/JPL/University of Arizona/Los Alamos National Laboratories; p. 107 NASA/JPL/Malin Space Science Systems; p. 111 JPL-Caltech-ASU/NASA; interior pages background (blue triangles) DiamondGraphics/Shutterstock.com.

CONTENTS

B roadly, a planet is defined as any relatively large natural body that revolves in an orbit around the Sun or around some other star and that is not radiating energy from internal nuclear fusion reactions. In addition to the above description, some scientists impose additional constraints regarding characteristics such as size (e.g., the object should be more than about 1,000 km [600 miles] across, or a little larger than the largest known asteroid, Ceres), shape (it should be large enough to have been squeezed by its own gravity into a spherei.e., roughly 700 km [435 miles] across, depending on its density), or mass (it must have a mass insufficient for its core to have experienced even temporary nuclear fusion).

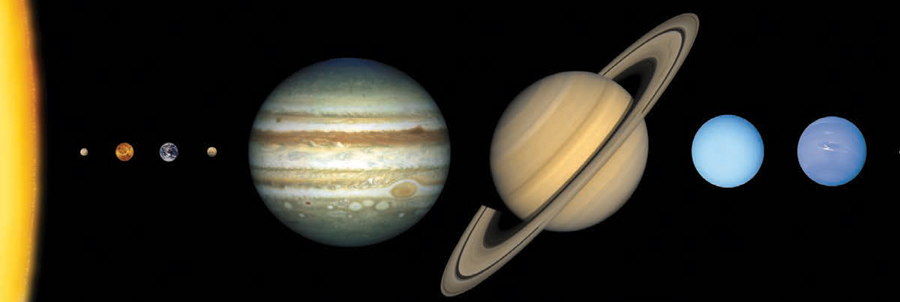

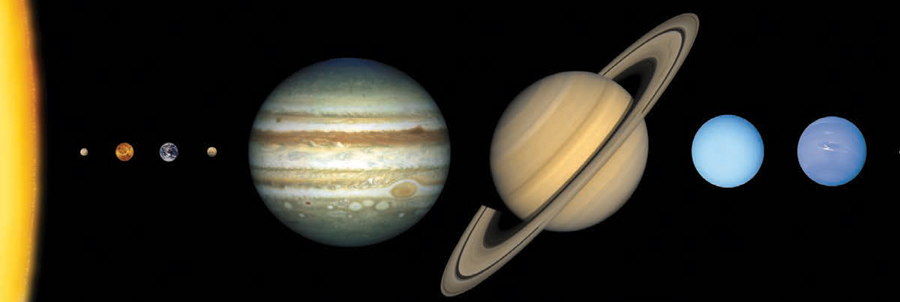

As the term is applied to bodies in Earths solar system, the International Astronomical Union (IAU), which is charged by the scientific community with classifying astronomical objects, lists eight planets orbiting the Sun; in order of increasing distance, they are Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune.

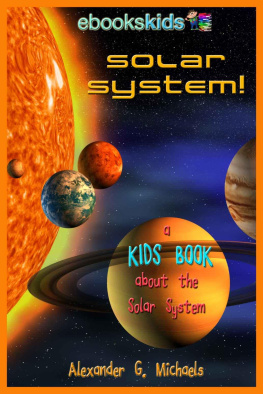

The planets can be divided into two groups. The inner planetsMercury, Venus, Earth, and Marslie between the Sun and the asteroid belt. The outer planetsJupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptunelie beyond the asteroid belt. The inner planets, are dense, rocky, and small. Since Earth is a typical inner planet, this group is sometimes called the terrestrial, or Earth-like, planets.

This illustration shows the approximate sizes of the planets relative to each other. The inner planets are the first four from the Sun (left) , noticeably smaller than the outer planets.

The inner planets, along with the Moon, have average densities in the range of 3.95.5 grams per cubic cm, setting them apart from the four outer, giant planets, whose densities are all close to 1 gram per cubic cm, the density of water. The compositions of these two groups of planets must therefore be significantly different. This dissimilarity is thought to be attributable to conditions that prevailed during the early development of the solar system.

The surfaces of the terrestrial planets and many satellites show extensive cratering, produced by high-speed impacts. On Earth, with its large quantities of water and an active atmosphere, many of these cosmic footprints have eroded, but remnants of very large craters can be seen in aerial and spacecraft photographs of the terrestrial surface. On Mercury, Mars, and Earths Moon, the absence of water and any significant atmosphere has left the craters unchanged for billions of years, apart from disturbances produced by infrequent later impacts. Volcanic activity has been an important force in the shaping of the surfaces of the Moon and the terrestrial planets.

We can learn a lot about Earth from our inner-planet neighbors. Mercury is too hot to retain an atmosphere, but Venuss brilliant white appearance is the result of it being completely enveloped in thick clouds of carbon dioxide, impenetrable at visible wavelengths. Below the upper clouds, Venus has a hostile atmosphere containing clouds of sulfuric acid droplets. The cloud cover shields the planets surface from direct sunlight, but the energy that does filter through warms the surface, which then radiates at infrared wavelengths. The long-wavelength infrared radiation is trapped by the dense clouds such that an efficient greenhouse effect keeps the surface temperature near 465 C (870 F, 740 K). Radar, which can penetrate the thick Venusian clouds, has been used to map the planets surface.

In contrast, the atmosphere of Mars is very thin and is composed mostly of carbon dioxide (95 percent), with very little water vapour; the planets surface pressure is only about 0.006 that of Earth. The outer planets have atmospheres composed largely of light gases, mainly hydrogen and helium.

The inner planets are similar to Earth in many ways and in other ways very different. This gives scientists great opportunities to study the nature and origin of Earth.

T he planet that orbits closest to the Sun is Mercury. It is also the smallest of the eight planets in the solar system. These features make Mercury difficult to view from Earth, as the small planet rises and sets within about two hours of the Sun. Observers on Earth can only ever see the planet during twilight, when the Sun is just below the horizon.

The difficulty in seeing it notwithstanding, Mercury was known at least by Sumerian times, some 5,000 years ago. In Classical Greece it was called Apollo when it appeared as a morning star just before sunrise and Hermes, the Greek equivalent of the Roman god Mercury, when it appeared as an evening star just after sunset. Hermes was the swift messenger of the gods, and the planets name is thus likely a reference to its rapid motions relative to other objects in the sky. Even in more recent eras, many sky observers passed their entire lifetimes without ever seeing Mercury. It is reputed that Nicolaus Copernicus, whose heliocentric model of the heavens in the 16th century explained why Mercury and Venus always appear in close proximity to the Sun, expressed a deathbed regret that he had never set eyes on the planet Mercury himself.