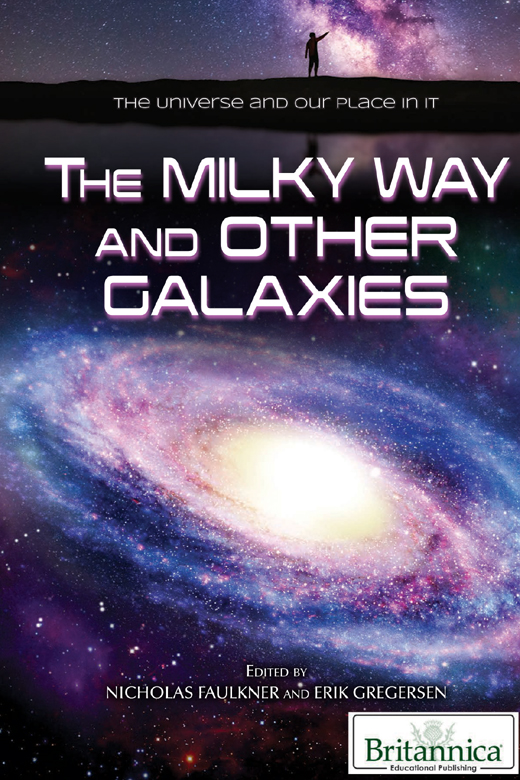

Published in 2019 by Britannica Educational Publishing (a trademark of Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc.) in association with The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc.

29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010

Copyright 2019 by Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc. Britannica, Encyclopdia Britannica, and the Thistle logo are registered trademarks of Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc. All rights reserved.

Rosen Publishing materials copyright 2019 The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc. All rights reserved.

Distributed exclusively by Rosen Publishing.

To see additional Britannica Educational Publishing titles, go to rosenpublishing.com.

Britannica Educational Publishing

J.E. Luebering: Executive Director, Core Editorial

Andrea R. Field: Managing Editor, Comptons by Britannica

Rosen Publishing

Nicholas Faulkner: Editor

Brian Garvey: Series Designer / Book Layout

Cindy Reiman: Photography Manager

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Faulkner, Nicholas, editor. | Gregersen, Erik, editor.

Title: The Milky Way and other galaxies / edited by Nicholas Faulkner and Erik Gregersen.

Description: New York : Britannica Educational Publishing, in Association with Rosen Educational Services, 2019 | Series: The universe and our place in it | Audience: Grades 7-12. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018013665| ISBN 9781538303955 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: GalaxiesJuvenile literature. | Milky WayJuvenile literature.

Classification: LCC QB857.3 .M55 2018 | DDC 523.1/12dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018013665

Manufactured in the United States of America

Photo credits: Cover (top), p. 1 Carlos Fernandez/Moment/Getty Images; cover (bottom) tose/Shutterstock.com; p. 8 Robert Williams and the Hubble Deep Field Team (STScI) and NASA; p. 10 Vaclav Janousek/Fotolia; pp. 12, 96 The Hubble Heritage Team (AURA/ STScI/ NASA); p. 15 European Space Agency and NASA; p. 19 Courtesy of Palomar Observatory/California Institute of Technology; p. 21 NASA, C.R. ODell and S.K. Wong (Rice University); p. 22 J.P. Harrington and K.J. Borkowski (University of Maryland), and NASA; pp. 25, 84 NASA, ESA, and The Hubble Heritage Team (STScI/AURA); p. 29 R. Gilmozzi, Space Telescope Science Institute/European Space Agency; Shawn Ewald, JPL; and NASA; p. 32 Viktar Malyshchyts/Shutterstock.com; pp. 36, 102 NASA; p. 38 AAS. Reproduced with permission; pp. 44-45 NOAO/AURA/NSF; p. 48 NASA, ESA, S. Beckwith (STScI), and The Hubble Heritage Team (STScI/AURA); p. 62 Local Group Galaxies Survey Team/NOAO/AURA/NSF; p. 71 GALEX Team, Caltech, NASA; p. 73 Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc.; p. 76 CFHT/NOAO/AURA/NSF/NASA/ESA/STScI; p. 78 NOAO/Science Source; p. 79 WIYN Consortium, Inc. 3.5-m Telescope/C. Howk, JHU/ B. Savage, U. Wisconsin/N. Sharp, WIYN/NOAO/AURA/NSF; p. 86 Visuals Unlimited, Inc./Robert Gendler/Visuals Unlimited/Getty Images; p. 97 Reinhold Wittich/Stocktrek Images/Getty Images; p. 98 Prof. Vincent Icke/Science Source; p. 100 B. Whitmore (STScI)NASA/ESA; p. 108 The Hubble Heritage Team; interior pages background (blue triangles) DiamondGraphics/Shutterstock.com.

CONTENTS

V irtually all galaxies appear to have been formed soon after the universe began, approximately 13 billion years ago. Measurements tend to suggest that most, if not all, galaxies have very nearly the same age and that they consist of stars and interstellar matterclouds of gas and particles of dustthat move together through space. Even small galaxies contain millions of stars, while the largest may have trillions of stars. And the universe is made up of trillions of galaxies, which are found all over the sky, even in the depths of the farthest reaches penetrated by powerful modern telescopes. The Sun and the solar system, including Earth, are part of the Milky Way Galaxy.

The Milky Way Galaxy is a large spiral system consisting of several hundred billion stars. It takes its name from the Milky Way, the irregular luminous band of stars and gas clouds that stretches across the sky as seen from Earth. Every star that can be seen from Earth without a telescope belongs to the Milky Way Galaxy.

The Milky Way Galaxy is an example of a spiral galaxy, which are shaped like pinwheels and have immense spiral arms. The Sun (as well as Earth) is located on the inner edge of a spiral arm, some 27,000 light-years from the nucleus, or centre, of the Galaxy. The Galaxys disk and spiral arms have a diameter of roughly 100,000 light-years. The Sun and all the other stars of the Galaxy take about 200 million years to orbit about the nucleus.

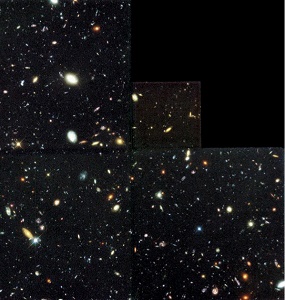

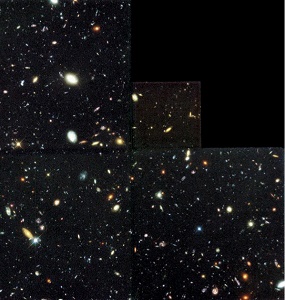

This image, the result of 10 days observation by the Hubble Space Telescope, shows 1,500 galaxies in different stages of their evolution.

Galaxies vary greatly in size and grow by colliding and merging with other galaxies. Some extreme dwarf galaxies found near the Milky Way Galaxy are only 100 light-years across, while large spiral galaxies typically have diameters of 100,000 to 500,000 light-years. On the other hand, giant radio galaxies, which are very strong sources of radio waves, extend more than 3,000,000 light-years.

Most galaxies move through the universe in clusters, sometimes in small groups and sometimes in enormous complexes. Isolated galaxies are quite rare. The Milky Way Galaxy, for example, belongs to the Local Group, which also includes the Magellanic Clouds, the Andromeda Galaxy, and about 50 other galaxies.

Evidence suggests that at the centre of many galaxies lies a supermassive black hole, a region of such intense gravity that nothing, not even light, can escape. Additionally, when two galaxies merge, their nucleiand black holescollide, generating an immense amount of energy. At the centre of the Galaxy is a massive black hole, named Sagittarius A*, and it has a mass about 4.3 million times larger than the Suns.

In the late 20th century a surprising finding was mademost of the mass in galaxies is not in the form of stars or other visible matter. Most galaxies have much more mass than can be accounted for by their stars. This means that they must contain some dark matter, from which no light is seen. The nature of this dark matter is not yet known.

This text studies the nature of the various types of galaxies, including our own. Scientists have only begun to understand the complexities of these immense celestial networks.

T he Milky Way Galaxy is the galaxy that we call home. Although Earth lies well within the Milky Way, astronomers do not have as complete an understanding of its nature as they do of some external star systems. A thick layer of interstellar dust obscures much of the Galaxy from scrutiny by optical telescopes, and astronomers can determine its large-scale structure only with the aid of radio and infrared telescopes, which can detect the forms of radiation that penetrate the obscuring matter.

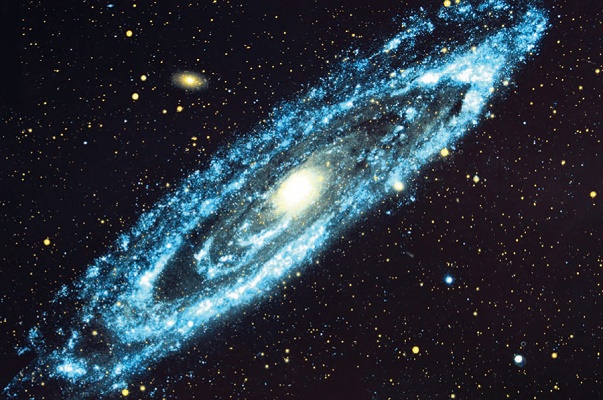

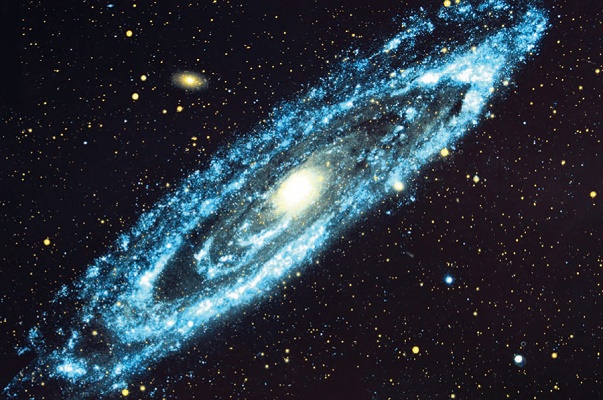

Artists rendition of the Milky Way Galaxy.

Although most stars in the Milky Way Galaxy exist either as single stars like the Sun or as double stars, there are many conspicuous groups and clusters of stars that contain tens to thousands of members. These objects can be subdivided into three types: globular clusters, open clusters, and stellar associations. They differ primarily in age and in the number of member stars.

The largest and most massive star clusters are the globular clusters, so called because of their roughly spherical appearance. The Galaxy contains more than 150 globular clusters (the exact number is uncertain because of obscuration by dust in the Milky Way band, which probably prevents some globular clusters from being seen). They are arranged in a nearly spherical halo around the Milky Way, with relatively few toward the galactic plane but a heavy concentration toward the centre. The radial distribution, when plotted as a function of distance from the galactic centre, fits a mathematical expression of a form identical to the one describing the star distribution in elliptical galaxies.