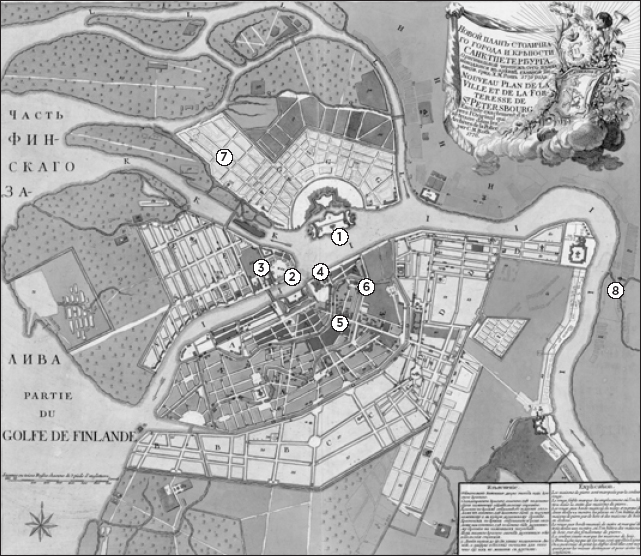

A HISTORY OF

FUTURE CITIES

DANIEL BROOK

For my parents

CONTENTS

Two of the cities featured in this bookcontemporary St. Petersburg and Mumbaihave gone by different names at different points in their histories. The cities will be referred to by the name in use during the period under discussion (e.g., St. Petersburg in the time of Catherine the Great; the Nazi siege of Leningrad).

One of the most captivating aspects of St. Petersburg, Shanghai, and Mumbai is that much of their historic architecture remains extant today. Buildings that have been destroyed will be described in the past tense (on the bells of St. Petersburgs Tercentenary Church, reliefs were embossed of each member of the royal family); buildings that still stand will be described in the present tense (Mumbais Regal [Cinema] faade boasts bas-relief masks of tragedy and comedy).

All quotations from outside sources are cited in endnotes. All other quotations come from in-person interviews conducted by the author.

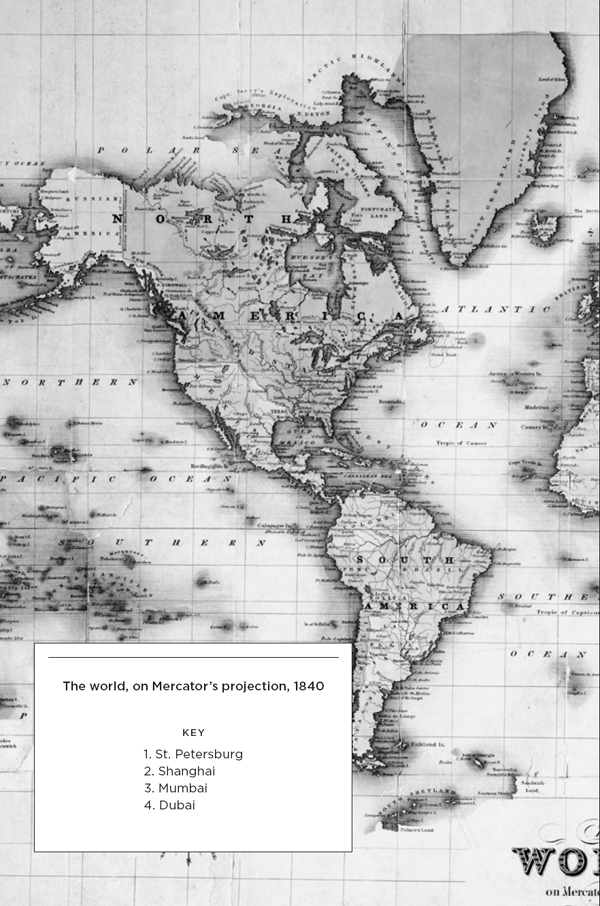

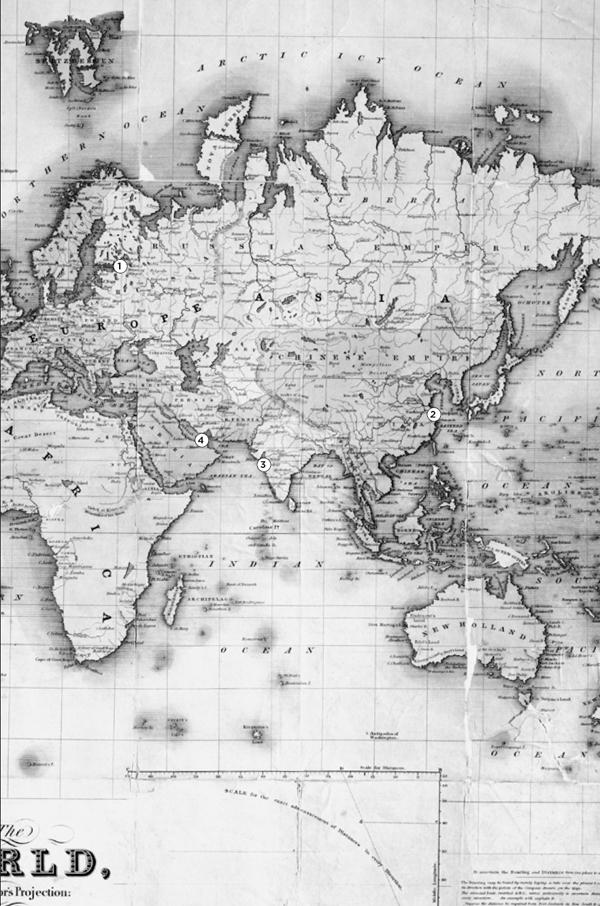

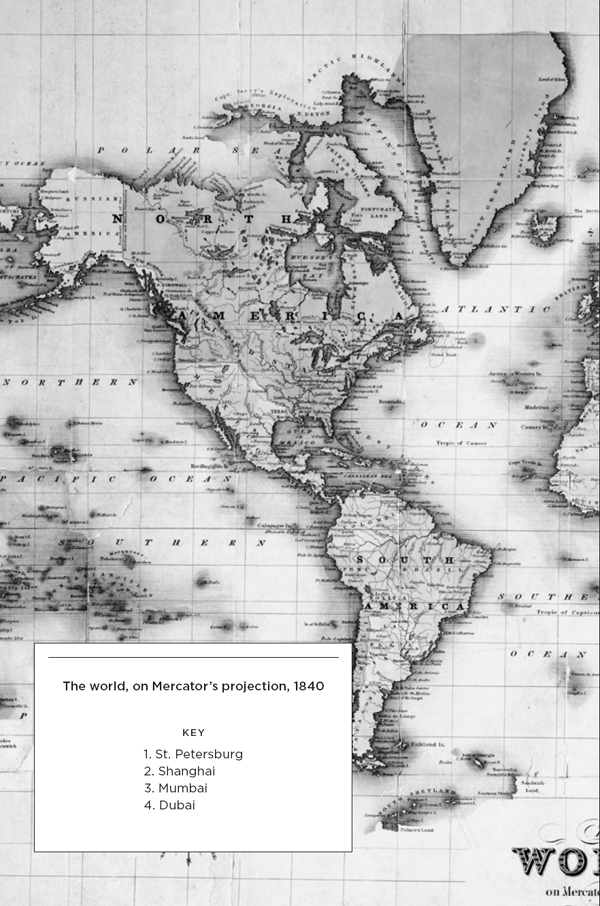

St. Petersburg, 1776

KEY

1. Peter and Paul Fortress

2. Kunstkamera

3. St. Peterburg State University

4. Winter Palace

5. Nevsky Prospect

6. Cathedral of Our Savior on Spilt Blood

7. Red Banner Factory

8. Okhta Centre (proposed site)

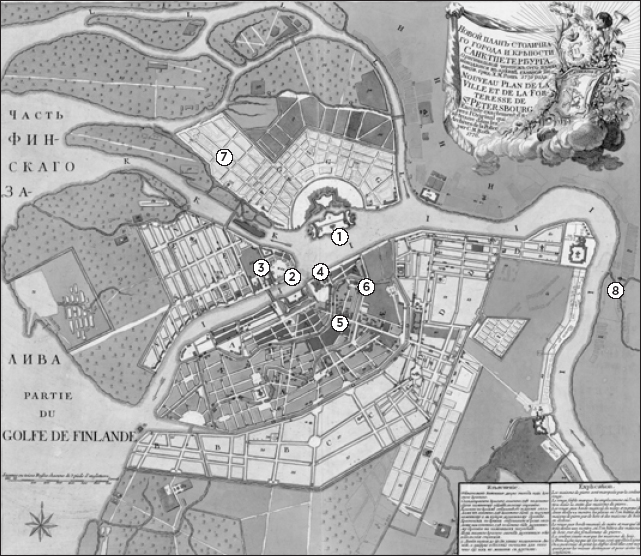

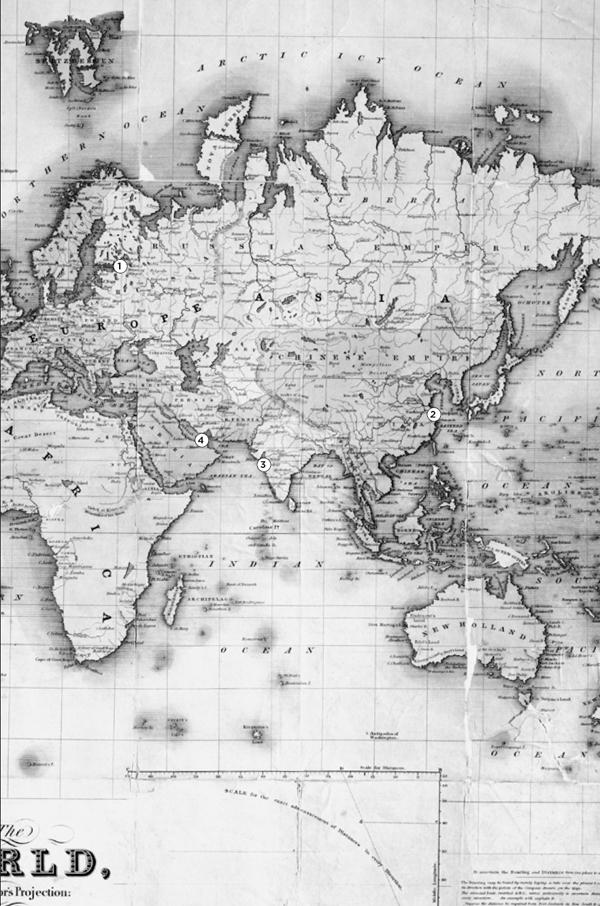

Shanghai, 1862

KEY

1. Shanghai Race Club (now Peoples Square)

2. Sincere and Wing On department stores on Nanjing Road

3. Great World

4. Cathay Hotel

5. Park Hotel

6. Oriental Pearl Radio and Broadcasting Tower

7. Jin Mao Tower

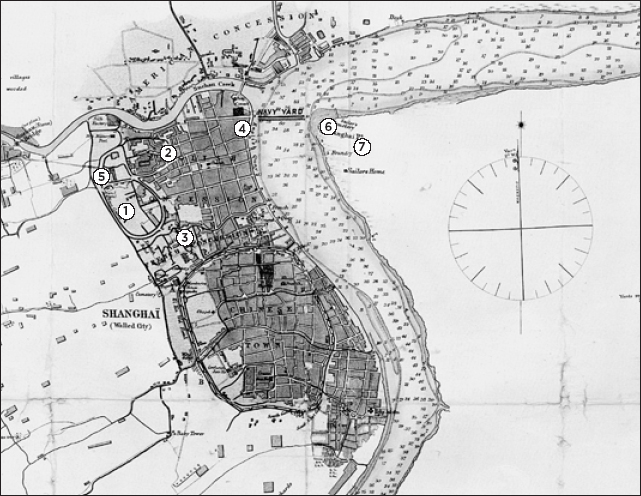

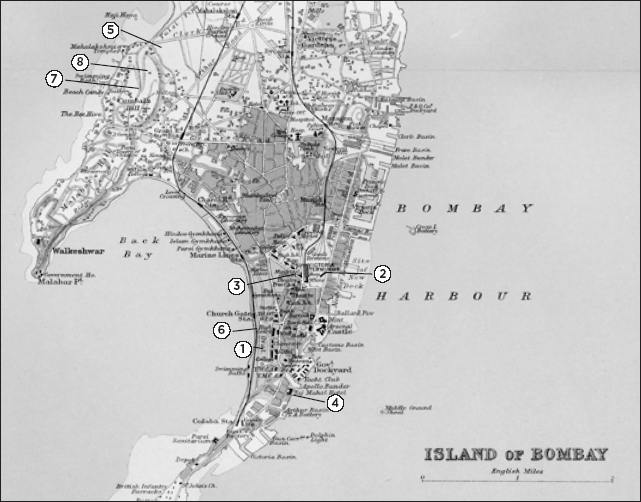

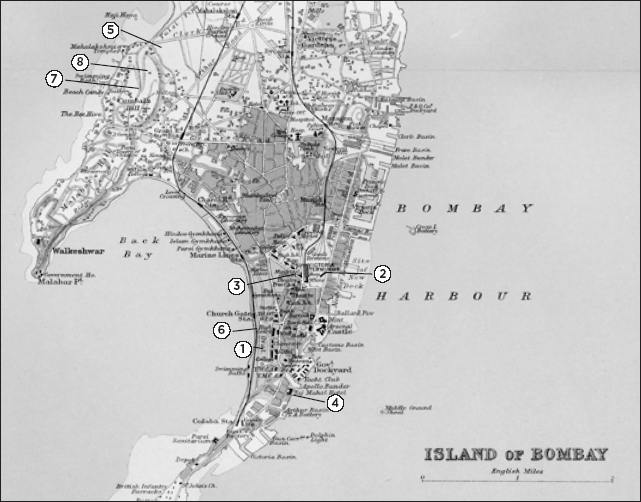

Bombay, 1909

KEY

1. University of Bombay (now University of Mumbai)

2. Victoria Teminus (now Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus)

3. Bombay Municipal Corporation (now Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai)

4. Taj Mahal Hotel

5. Willingdon Sports Club

6. Eros Cinema

7. Antilia (Mukesh Ambani residence)

8. Imperial Towers

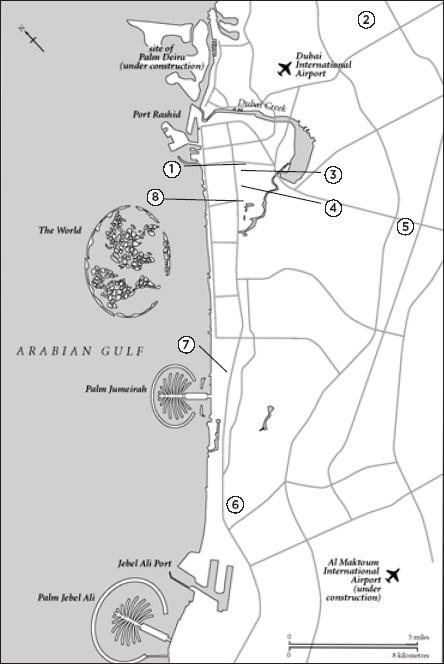

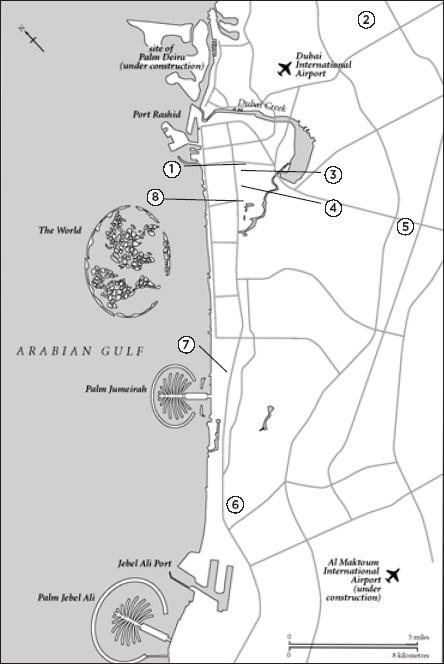

Dubai, 2010

KEY

1. Dubai World Trade Centre

2. Sonapur labor camp

3. Emirates Towers

4. Dubai International Financial Centre

5. Dragon Mart

6. Ibn Battuta Mall

7. Twin Chrysler Buildings

8. Burj Khalifa

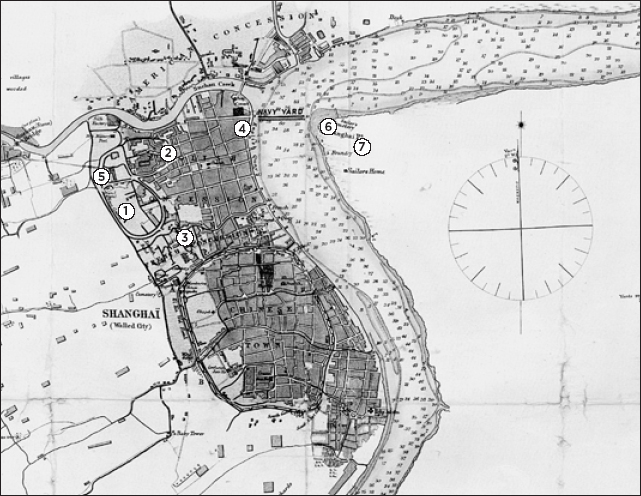

An Orientation

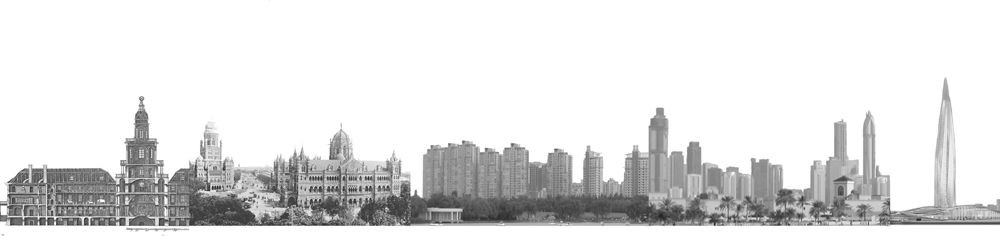

University of Mumbai Convocation Hall

W here are we?

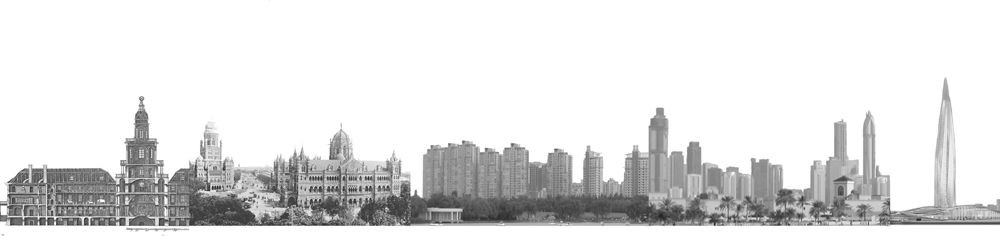

Walking through the cityscapes of St. Petersburg, Shanghai, Mumbai, and Dubai provokes this same question. Built to look as if they were not where they arein Russia, China, India, and the Arab world, respectivelyeach metropolis conjures the same captivating yet discomfiting sense of disorientation. In the heart of St. Petersburgs royal palace sits a lavish room of archways and fresco panels cribbed directly from the Vatican in Rome; only the falling snow outside the window calls its bluff. In Shanghai, 1920s Art Deco hotels look like Jazz Age skyscrapers from Manhattan magically airlifted to a city so far from New York that watches need not be reseta.m. simply becomes p.m. In Mumbai, the 150-year-old Gothic university campus is an odd Oxford planted with palm trees, while Dubais twin Chrysler Buildings make visitors wonder: Who thought if one fake Chrysler building was good, two would be even better?

These four unlikely sister cities are unified by the sense of disorientation they impart. They are disorienting cities because each was purposefully dis-orient-ed.

Orient is both a noun and a verbthe noun means east; the verb means to place oneself in spacebut its two meanings are intertwined. An individual lost in the wilderness can place herself in space (orient herself) because she knows that the sun rises in the east (the Orient). The disorientation imparted by St. Petersburg, Shanghai, Mumbai, and Dubai results from their being located in the East but purposefully built to look as if they are in the West. Their occidental looks are anything but accidental.

For Western visitors to these cities, love/hate reactions are common. Travelers in India sometimes relish Mumbai, Indias most international and developed city, as a respite from the foreignness of the subcontinent. In the Raj-era-built downtown, auto-rickshaws, the cacophonous three-wheeled pods that serve as taxis throughout the rest of the country, are banned. Even roaming street-cows, perhaps the most quintessential feature of Indian urbanism, are rare. Constructed to look like a tropical London, the ruse works as the tidal throngs of commuting stockbrokers and secretaries flow toward their Victorian Gothic office buildings each morning from a train station based on St. Pancras in the British capital. And yet, this ersatz London of stately banks and red double-decker buses often drives Western travelers to the hinterlands to take in the real India.

Verdicts on Dubai are typically harsher. Whitewashing away its local traditions by speaking English rather than Arabic, shopping in malls rather than souks, selling pork in its supermarkets, and pouring drinks in its hotels, it is a city where the traditions of the Arab world have been intentionally muted to make way for a placeless, tasteless global future. Without the charm of history, which turns knockoff buildings like Mumbais aped Oxford into heritage architecture, the Las Vegas of the Middle East is mocked as an entirely fake metropolis with no culture at all.

Yet love them or hate them, these dis-orient-ed metropolises matter. They are places to be reckoned with because they are ideas as much as cities, metaphors in stone and steel for the explicit goal of Westernization. Thus the BBC could hold a formal televised debate in 2009 on the resolution, This house believes Dubai is a bad idea, in a way that they could never devote a similar program to St. Louis. For unlike Dubai, St. Louis is not an idea; St. Louis is just a place.

Whatever visitorsor the BBCs live studio audiencemake of the developing worlds dis-orient-ed cities, what their own people make of them matters more. The question bedeviling visitorswhere are we?is far less fraught than the question these cities provoke for their own people: Who are we? These global gateway cities raise the question of how to be a modern Arab, Russian, Chinese, and Indian, and whether modernization and globalization can ever be more than just euphemisms for Westernization. In the older cities of St. Petersburg, Shanghai, and Mumbai, different answers to this question have been built into the cityscape over the centuries. Each neighborhood offers a different periods vision of the Russian, Chinese, and Indian future. But even in the most historic of these cities, what is most captivating is not what has been built but what could be built. The reason these cities matter is that their founding promise endures: to build the future.

Next page