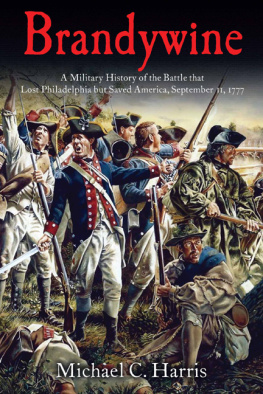

To the men of both sides

who served along the Brandywine

Table of Contents

Maps have been placed throughout the book for the convenience of the reader .

Preface

An Oft-Overlooked Battle

Until recently, Americans have been preoccupied with victories on the battlefield, and have preferred not to be reminded about past mistakes. Much more time and effort has been spent, for example, studying American victories during the Revolution such as Trenton, Princeton, Saratoga, and Yorktown, than defeats. The lack of study or deep interest in the September 11, 1777, battle of Brandywine is perhaps a reflection of our interest in victories and turnings points. The combat along the Brandywine was neither.

The Brandywine defeat has been relegated to a minor role in American historiography. This lack of attention is both wholly undeserved and rather shocking given that more troops fought along the Brandywine (nearly 30,000) than during any other battle of the entire American Revolution, its 11 hours of fighting make it the longest single-day battle of the war, and it covered more square miles (10) than any other engagement. Invariably people are surprised when they hear those three facts about Brandywine. And yet, it remains one of the least known or understood large-scale engagements of the Revolution.

The Early Context

Most early studies of the Brandywine were written by area residents who over-emphasized the local role in the battle, and in so doing developed a host of unsubstantiated facts that have assumed in some cases near-mythological proportions. Well-researched histories with the battle as the primary focus are few and far between.

The earliest accounts were written within days of the fighting by participants from both sides. British accounts are almost all recitations of battle-related events. Several important broader themes, however, run through the early American accounts. Some reflect the belief that a new form of government would come out of the battle and eventually the war. Others reflect the central role religion played in the lives of Americans in the late eighteenth century, with divine providence seen guiding all events. A general order published soon after the battle supported these notions when Washington proclaimed to his troops: Altho the event of that day was not so favorable as could be wished, the General has full confidence that in another Appeal to Heaven we shall prove successful.

Over time, other accounts of the September 1777 battle clouded these contemporary recollections and helped shove Brandywine into the shadows. Later histories of the war focused on a few high-profile individuals whose reputations had the power to arouse their fellow citizens, and not research-based studies of the actual event. They presented the Revolution as an event of importance for all mankind due to the emergence of the new republica great human event thanks to Gods guidance.

For much of the nineteenth century, local and state history emphasized the regions role in shaping the national republic. And with these dramatizations, myths of a different variety took form and root.

Mythologies

Jacob Neffs 1845 history of the American Revolution devoted part of a chapter to the battle of Brandywine. Neffs work was heavy on poetic prose but light on details, focusing instead on American gallantry and the defeat of the invaders. With great disadvantage on the part of the Americans (who were also much inferior in numbers and in arms), proclaimed Neff, the armies rushed together in fierce and desperate conflict. In fact, the Americans were not outnumbered, and they were armed no worse than the men serving under William Howe. Neffs work also discussed the role of the Marquis de Lafayette and his gallant wounding, and heaped praise on Nathanael Greene:

General Greene came up with the reserve, and, by a singularly skilful maneuver, opened his ranks for the fugitives, and after they had passed through, like a father protecting his children, closed his ranks behind them, checked the pursuit of the enemy by the fire of his artillery, and completely covered the retreat. This, with many other splendid achievements, invests the character of Greene with an air of romance, which will always be felt by the American people, and elicit unbounded praises from the unborn Homers of our country.

George Bancrofts 1866 history of the United States includes a military study of the battle and campaign. Although a monumental achievement for its time, Bancrofts study was riddled with errors and continued the theme of hero worship: As Washington rode up and down his lines the loud shouts of his men witnessed their love and confidence, and as he spoke to them in earnest and cheering words they clamored for battle.

Bancrofts book also mentions the engagement of Hessian troops, and refers to the vigorous charge of the Hessian and British grenadiers, who vied with each other in fury as they ran forward with the bayonet.remained genuinely angry that King George hired Germanic troops to fight against them. As a result, most histories of the Revolution and the battle overemphasized the rolereal or imaginedof those troops.

An 1881 history of Chester County, Pennsylvania, includes another basic account of the battle that includes several incorrect and undocumented claims. The study perpetuates the notion, for example, that Americans went into the battle with subpar weaponry. This belief lived on for most of the next century even though there is no primary evidence to support this claim.

The Country and Interpretations Evolve

By the end of the nineteenth century, America faced several changes that influenced how the story of the Revolution was told. The transformation from a collection of rural economies into an industrialized nation after the Civil War tarnished the idealistic view many Americans had about their nation. The earlier period had glorified war and emphasized the greatness of heroes such as Washington and Lafayette, but the carnage wrought by the Civil War went a long way toward eliminating that mindset. The postwar industrialization, coupled with the massive influx of European immigrants brought class struggles to the forefront of the American consciousness. The writing of history started to emphasize the role of the common man rather than heroes or the upper class.

A series of historical markers were placed on the Brandywine battlefield in 1915. The dedication ceremonies included a presentation on the history of the battle by a Professor Smith Burnham. The professors speech continued to note certain heroes, though in a much subdued manner. For example, he emphasized the minor role played in the battle by the young John Marshall, future chief justice of the United States. The importance of the common man theme to the ultimate victory and formation of the country made a forceful appearance when he focused on a handful of local participants. Religion played no role in this account.

Up to this point in American historiography, the heroes of the American Revolution, men like Washington, Greene, and Lafayette, had been glorified as great men. But as the American Progressive movement gained prominence in the early- to mid-twentieth century, the emphasis shifted to social history. As the role of the common man gained ground and the emphasis on heroes faded, war was interpreted along socioeconomic rather than political or military themes. With less emphasis on military themes, nearly all the accounts about the Brandywine penned during this period were written by residents of the region. No scholarly histories of the battle were published during this period.