1. | Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery, established 1918, dedicated 1937.

THE WEATHER WAS PERFECT during a week in June when I drove through western Belgium and northeastern France on a tour of First World War battlefields, cemeteries, and memorials. My trip began in the Flemish town of Ypres, which had been the site of intense fighting throughout the four-year conflict. While strolling on the ramparts, I came across a tiny British cemetery nestled above a bend in the Yser River. Nearby, and far grander, looms the Menin Gate, a neoclassical monument dedicated to 55,000 British soldiers who died at Ypres. In a nightly ceremony conducted at the stroke of 8 p.m. year-round, a British soldier trumpets a poignantly beautiful Last Post in honor of those who fell in defense of the Empire.

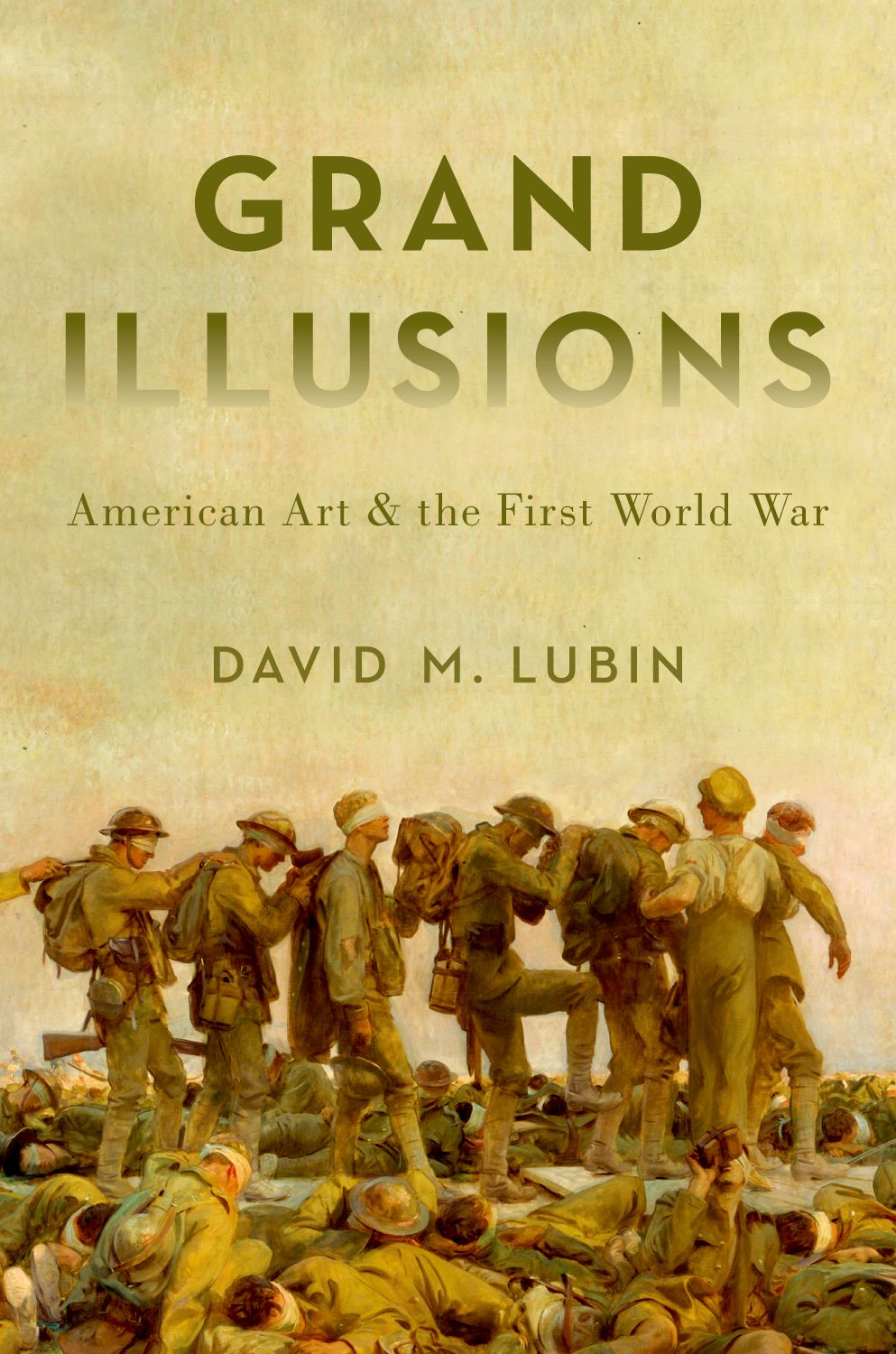

Over the next six days, I sought out war cemeteries large and small. All were beautiful, well-manicured, and humbling. I especially remember one little French military cemetery perched on a hillside overlooking a twelfth-century Cistercian abbey. Other graveyards were majestic, none more so than the Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery and Memorial, spread out over 130 acres and containing the largest number of American war dead (14,246) of any American cemetery in Europe. Here, in hypnotic row upon row of white marble crosses, interspersed with the occasional Star of David, were the remains of thousands of American soldiers who never returned to their homeland ().

The scene called to mind a slide lecture I heard while in graduate school by the renowned art historian Vincent Scully. Describing the truncated tower that visually anchored another of Americas World War I cemeteries in France, he became suddenly emotional, comparing the tower to the truncated lives of the young men buried there. His voice broke as he said the words, and he had to gather himself before moving on to the next slide. This triggered in me, and Im guessing everyone else in the darkened auditorium that day, a similar response.

A third of a century later, I found myself questioning the emotions I had experienced in that lecture hall. Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori, said the ancient Romans. But is it sweet and fitting to die for your country?

A few kilometers beyond Ypres, I visited the Tyne Cot cemetery, permanent home to the bodies of twelve thousand soldiers of the British Commonwealth, eight thousand of them unnamed. Their graves, set neatly within herbaceous borders and marked by simple white crosses in undulating patterns on a gentle slope, are surrounded by pastoral farmland that might have reminded family members of countryside back home, thus making good on the plea of the British war poet Rupert Brooke: If I should die, think only this of me: / That theres some corner of a foreign field / That is for ever England.

2. | Kthe Kollwitz, Grieving Parents, 19311932, in the German war cemetery, Vladslo, Belgium.

Some fifty or sixty kilometers from Tyne Cot, outside the village of Vladslo in Western Flanders, lies a German cemetery. Getting there is difficult; the roads are small and the signage minimal. When I found the place at last, a German religious group was just leaving, singing a Lutheran hymn at the entrance gate before boarding their coach for another destination. With them gone, I had the graveyard to myself. What a contrast to the British cemeteries. This resting place was dark and enclosed, shaded by large, leafy trees, as if even the sky was to be blotted out. The markers indicated that the bodies were buried eight to a grave; obviously the dead on the losing side did not merit the real estate accorded to their counterparts on the winning side.

In the back of the cemetery was the monument, or anti-monument, that I had come to see. This was the Grieving Parents double-statue by the German sculptor and printmaker Kthe Kollwitz, whose son Peter had died fighting in Flanders (). Kollwitz depicts herself and her husband, each stricken with grief for their lost child. They occupy separate plinths. The distance separating them is small but immeasurable, for grief is the most private of emotions. There is nothing noble about it. Nor is there in death for the homeland. That, it seems to me, is what Grieving Parents has to say. It haunted me throughout my journey.

IN 1937, CAPPING AN ALMOST decade-long international trend in favor of pacifism, the left-wing humanist French filmmaker Jean Renoir made a movie about a small group of French soldiers from different social classes who serve time together in a series of German prisoner-of-war camps. He entitled it La grande illusion (and, in doing so, probably had in mind the title of the British author Norman Angells 1909 antiwar tract, The Great Illusion