Also by Thomas F. Madden

Copyright 2016 by Thomas F. Madden

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

PREFACE

Though all other cities have their periods of government and are subject to the decays of time, Constantinople alone seems to claim a kind of immortality and will continue to be a city as long as humanity shall live either to

Pierre Gilles, The Antiquities of Constantinople (1548)

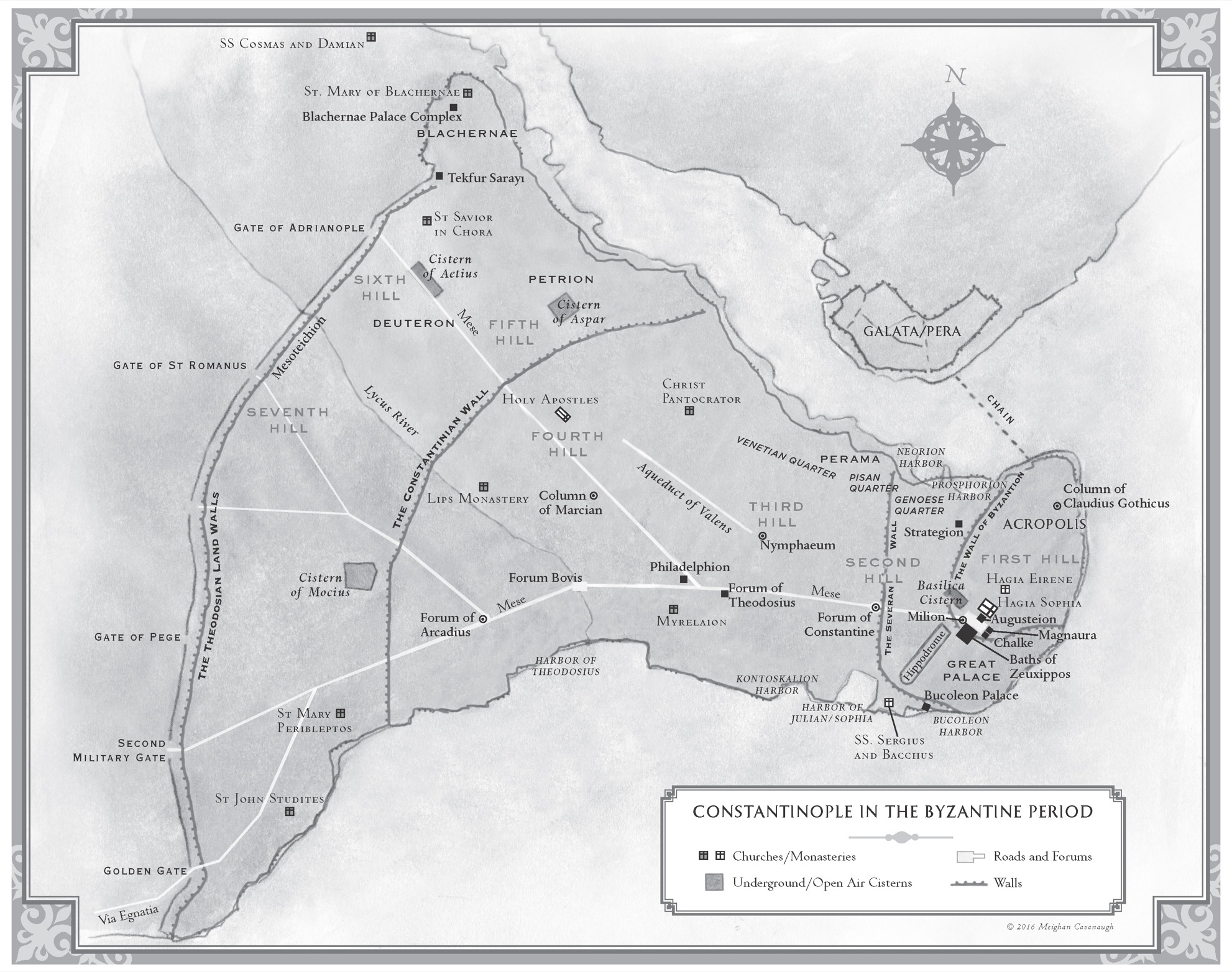

O n the waves of the Sea of Marmara bobbed dozens of Greek triremes, sails full of wind, oars slapping noisily against the rowdy waters as they strained against the southern currents. Ahead to the north surged the Bosporus Strait, famed for dashing vessels against the walls of its rocky cliffs. Beyond that was Pontos Axeinos, the Inhospitable Sea, where pirates roamed and warlike tribes watched hungrily from the wooded shores. Pressing defiantly northward, the vessels entered the Bosporus. A few miles of hard going later, they shifted their sails and rudders to turn sharply west, toward the opening of a river there. Skirting easily into the placid waters of the natural harbor, the sailors disembarked, hauling their supplies onto shore. To the south rose the green hills of a verdant peninsula, thrusting out against the maw of the Bosporus. A half hours climb up a nearby hill at the tip of the peninsula rewarded them with a breathtaking panorama of their new home. They stood in Europe, yet just across the strait to the east they could see the shores of Asia. Perched on the Greek frontier, they looked north to the endless Thracian forests and the Bosporus waterway, leading to mythical places unknown. It was here, around the year 667 BC, that these few hundred settlers broke ground on a bold new settlement.

Although in time it would grow in ways those colonists could never imagine, the city would ever remain suspended between worlds: Greeks and Persians, Western Romans and Eastern Romans, Catholics and Orthodox, Europeans and Asians, Christians and Muslims, West and East. In its many incarnations it would by turns become a den of debauchery, a city of saints, a smoldering ruin, and a glistening capital of two empires. It would be hailed as the greatest Christian city in the world before converting to Islam, taking on the mantle of the Muslim caliphate.

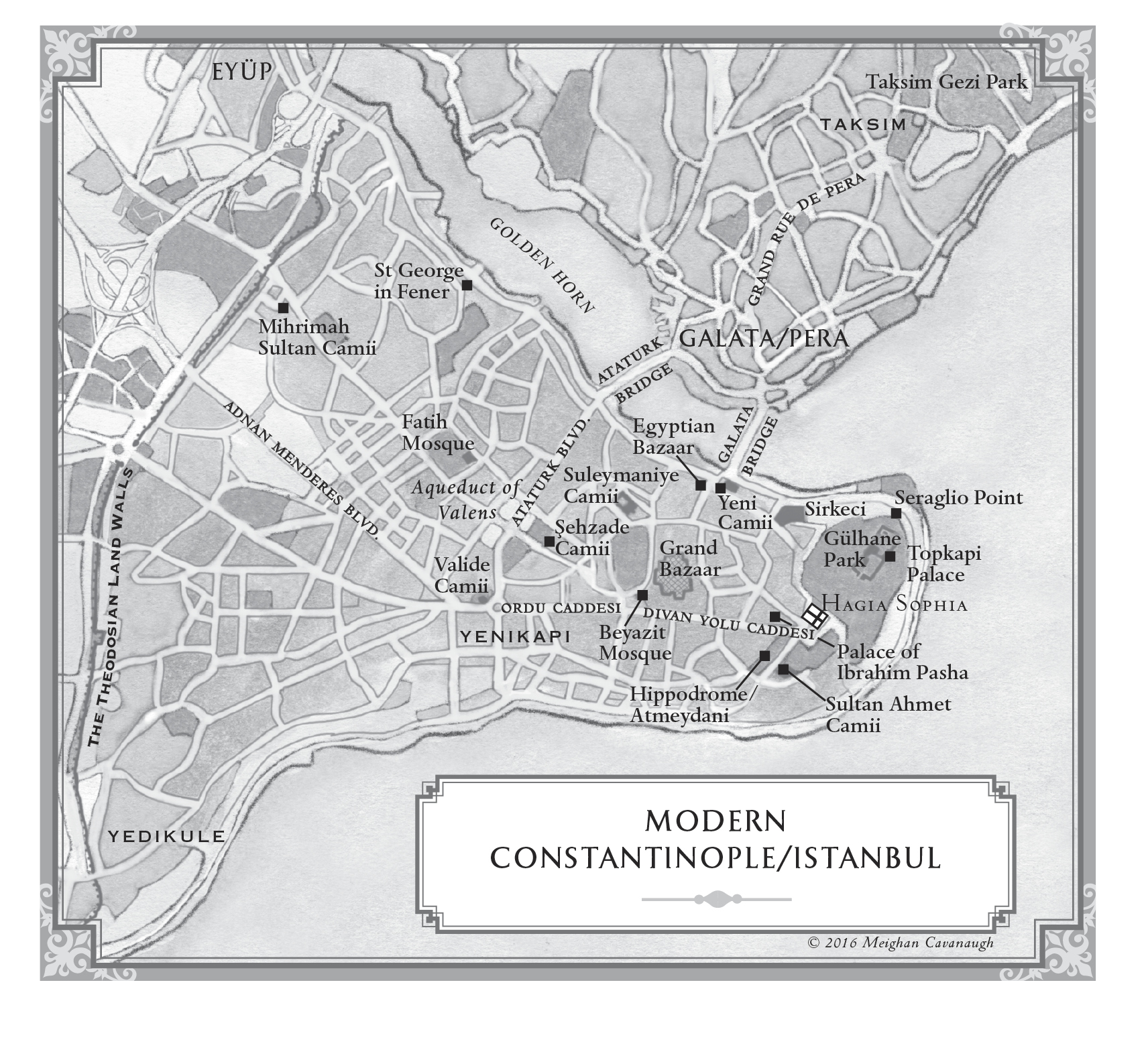

Today it is Istanbul. Yet across the centuries it has answered to many names: Byzantion, New Rome, Antoniniana, Constantinople, Queen of Cities, Miklagard, Tsargrad, Stamboul, Islambul, the Gate of Happiness, and perhaps most eloquently of all, the City.

It remains the City. Istanbul is simply a Turkish hearing of the Greek phrase , meaning in or to the City. It was an appropriate name, for across the centuries it so dwarfed all other cities that it seemed to stand completely apart. It mattered little whether one was a thousand miles away from its majesty or just across the strait that splashed against its massive walls. The City was always the megalopolis on the Bosporus, set like a jewel between two continents and two seas.

It is hard not to stand in awe when considering the extraordinary history of this extraordinary place. Once, it was a magnificent city of rulers, a place in which geography conspired to give it dominion over its horizons. From its sprawling palaces, historys most powerful men sent forth commands to the distant reaches of their vast empires. The empires obeyed, revering their capital, showering it with wealth, adorning it with architectural marvels, and lifting it up to become a city above all others.

Although it has marked the passage of more than twenty-five centuries, Istanbul is no ruin of antiquity. It remains a vibrant, energetic, and exceedingly prosperous place. With nearly fifteen million inhabitants, Istanbul is today Europes largest city, and the fifth largest in the world. Its financial districts are packed with modern skyscrapers teeming with commercial activity. Rapid increases across all sectors of Istanbuls economy form the engine that drives consistent and impressive growth throughout the entire country. After substantial increases post-2010, Turkeys economy was still growing at twice the rate of that of the European Union in 2014. Istanbuls rising prosperity is evident enough in its revived neighborhoods, beautiful parks, and flourishing art communities. Indeed, Istanbul has become one of the worlds premier tourist destinations, touted regularly by the New York Times and the Wall Street Journal as a place of exotic delights, intriguing history, and a multitude of cultural attractions. Today Istanbul is known as much for its thriving art scene and chic restaurants as for the beauty of the Blue Mosque and the splendor of Topkapi Palace.

The purpose of this book is to bring together the history of this urban marvel into one enjoyable and clear narrative. It is, from the outset, an impossible task. The history of Istanbul is so complex, stretching across so many cultures, events, and lives, that a library of books would not suffice to capture it. Yet if the entire story cannot be told, at least the most important episodes and broadest vistas can be sketched. The overarching goal here is to open up the rich history of Istanbul to any interested reader, while offering guideposts along the way for further exploration. It is well worth the trip. The history of Istanbul is bound tightly to the history of the Western world. All the currents of Mediterranean commerce, thought, religion, and power ran through Istanbuls roads, wharfs, forums, and palaces. It is impossible to study antiquity, the Middle Ages, Christianity, or Islam without sailing past Istanbuls shores, visiting its academies, poking ones head into its churches and mosques. Then as now, it remains the City.

My own fascination with Istanbul grew out of my study of the Middle Ages. While an undergraduate student, I was astonished to learn that long after the Roman Empire in Europe fell, it held lustily on to life in this city. There the forums remained full, the charioteers raced, and the emperors still ruled amid unrivaled splendor. I first visited Istanbul in 1986, at the beginning of my doctoral studies in history. American tourists were few. Conditions in the city, even in the core areas around the Blue Mosque, were poor. The smells of Istanbul were an unforgettable and inescapable part of the scenery. Some were pleasant, such as the savor of a street dner kebab or a wood-grilled fish on the wharf. But most were not. The worst were the cocktails of diesel exhaust belched from buses, raw sewage, and garbage piled on the streets, garnished with the stifling odor of the polluted Golden Horn waterway. Istanbuls taxis jammed the streets, piloted by men with a hand perpetually on the horn and windows down to bellow at other drivers or unlucky pedestrians. I loved it anyway. For, just beneath the crowded, noisy, malodorous chaos were layers upon layers of historical grandeur. Fourteen-century-old Hagia Sophia could be entered for the equivalent of fifty cents, and there were never lines. Ditto for the nearby Basilica Cistern. A venue for lavish functions and concerts today, the ancient Binbirdirek Cistern was entered through a hole in the ground where an old man rented flashlights to those brave enough to explore the rat-infested cavern.