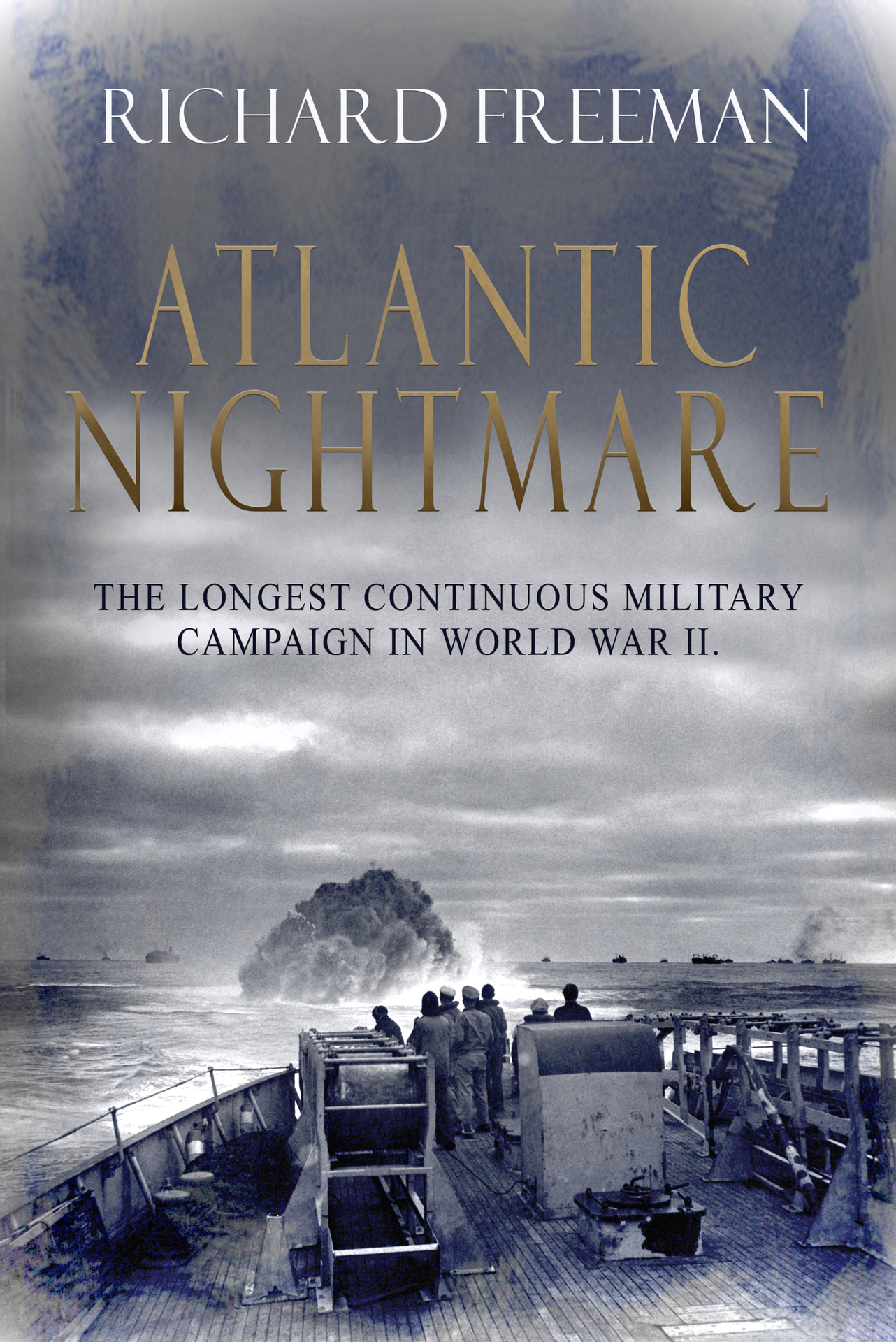

Atlantic Nightmare

Richard Freeman

Copyright Richard Freeman 2019

Richard Freeman has asserted his rights under the Copyright, Design and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the author of this work.

First published in 2019 by Endeavour Media Ltd.

Table of Contents

Preface

Preface

No battle lasted longer than the 2075 days of the Battle of the Atlantic. Few battles are so apparently perplexing in their outcome. There was nothing in the dark days of September 1939 to February 1943 to suggest that the Allies could defeat the U-boat menace. Yet two months later the U-boats were tamed.

This book explores the tactics and strategy of the two sides and reveals how consistently admirals Raeder and Dnitz pursued ill-chosen strategies for the U-boat war. Central to their failure were their seven strategic errors. These are summarised at the end of the book. The analysis justifying this list is presented in the book itself.

A glossary of technical terms also appears at the end of the book.

Note:

Ships weights are given in gross tons.

Gross tonnages, cargo weights and tonnages sunk have been rounded for ease of reading.

Times, except in quotations, are given in twelve-hour format.

Part 1: Skirmishes

1 Convoy SC-7

October 1940

The steam ship Trevisa was a mere 1800 tons a negligible spot on the vast Atlantic Ocean. She had been built in Londonderry in 1915 and had peacefully ploughed the seas since then. On the night of 16 October 1940 she was just one of 35 merchant ships in Convoy SC-7. They had departed from Sydney, Nova Scotia, 11 days earlier. Six days out, the convoy had run into a fearsome gale. Trevisa was one of several ships that fell behind an unprotected straggler.

The huge convoy covered five square miles of sea. At its centre were three columns of five ships. To either side were two columns of four ships. At the head of the centre column was Vice Admiral Lachlan Mackinnon, the convoy commodore. Mackinnon had already guided eleven convoys across the ocean before his command of the fateful SC-7. He had entered the navy in 1898 and seen action during the First World War, including at the Battle of Dogger Bank and the Battle of Jutland. His last post before retiring in 1939 as vice admiral had been as commander of the Second Battle Squadron. Along the way, he had been honoured by the Turkish Navy in 1911 and awarded the Legion of Honour by the French government in 1919. None of this had prepared him for what was now to come.

Mackinnon had taken up command of the convoy in the Assyrian , which was carrying 3700 tons of grain. (Convoy commodores usually selected one of the larger and faster ships to carry them in a particular convoy.) Strict radio silence meant that Mackinnon had to herd his 35-strong convoy by flags and aldis lamps. For this, he had with him his trusted team of five naval sailors. All his commands would be executed by his yeoman signaller and his two telegraphists. The flags themselves would be run up by his two young bunting tossers.

SC stood for slow convoy. The ships were weighed down by their bulk cargos of grain, coal, timber and steel. With favourable seas slow meant about eight knots. But Trevisa , with her 460 standards of timber, could not keep up. Her master, Robert Stonehouse, and his crew of 20 must have foreseen their fate as they slipped further and further behind. It came at 3.50 am. A single torpedo from U-124 struck the struggling Trevisa aft. Stonehouse was unaware that Korvettenkapitn Georg-Wilhelm Schulz had fired on his vessel the previous evening. But Schulz who would prove to be a U-boat ace had doggedly tracked the Trevisa through the night. This was his fourth sinking of the war. Another 15 would follow.

The loss of the Trevisa was a small-scale event. Even the human cost was not as bad as it might have been. Stonehouse and 13 of his seamen were picked up by the corvette HMS Bluebell and taken safely back to Gourock in Scotland. But her sinking was part of a much greater tragedy. Convoy SC-7 was no ordinary convoy. It was to prove to be one of the most deadly of the war.

One reason for the massacre of Convoy SC-7 was its inadequate escort. The 1000-ton sloop HMS Scarborough , described by the war hero Captain Donald Macintyre as a lightly armed warship designed for peacetime police work on distant foreign stations, was the sole escort for the first three-quarters of the convoys passage. Her commander, Norman Dickinson, was a career naval officer who had held that rank since 1936. The tragedy that was to come was no fault of his. Indeed he was to end the war much decorated and with the rank of captain. The odds, though, were overwhelmingly against the convoy from the moment it had set sail in so ill-protected a manner.

It was now 17 October. The convoy was nearly home. Dickinson was relieved to see the sloop HMS Fowey and the corvette HMS Bluebell taking up station alongside Scarborough . But even with this reinforcement the escort was still perilously thin. The escorts stood six miles apart. As Dickinson well knew, the gaps were more than wide enough for a U-boat to sneak through unseen.

Unknown to Dickinson, the ace U-boat commander Heinrich Bleichrodt in U-48 had found the convoy on 16 October. Bleichrodts prompt signal to Admiral Karl Dnitz in Lorient ensured that a wolf pack would soon be gathering ahead of the convoy. Meanwhile U-48 went hunting alone. Bleichrodts first victim was the 9500-ton tanker Languedoc . She was an easy target. A single torpedo slammed into her. Thinking that he had dealt with the tanker, Bleichrodt turned away to seek more prey. But, severely damaged as she was, Languedoc failed to sink. Her commander, John Thomson, called for assistance from Bluebell . Thomson and his 38 seamen boarded the corvette and four days later were safely landed at Gourock. It was left to Bluebell to sink Languedoc by gunfire.

Bleichrodts second torpedo sank the 4000-ton Scoresby , loaded with 1700 fathoms of pit props, desperately needed for Britains coal mines. Once more, the nearby Bluebell moved in to rescue the crew. A few hours later another straggler, the 3500-ton Greek-owned Aenos , was shelled and sunk by U-38 . Her crew, drifting in open boats in the empty ocean, thought that their last hours had come. But they were to be amongst the luckiest of all the many victims of this horrendous convoy. Along came a fellow-straggler the Canadian steamer Eaglescliffe Hall and pulled the men from the water.

Mackinnon had had a busy day directing his escort vessels in their rescue work and keeping the convoy in formation. The attacks and sinkings were regrettable, but not out of line with what he had come to expect. But the convoy was nearing the dangerous Western Approaches the U-boats favourite hunting ground at this stage of the war. During the next three nights the wolf packs would be out, searching for their prey. And, however spread out convoys were in the vastness of the Atlantic, they were compelled to converge as they neared port. That made them easier targets for the U-boats to locate. At least, though, the convoy now had the additional protection of Fowey and Bluebell .

Mackinnon was relieved when dawn broke on 18 October. There were just three more sailing days to port and he had only lost three of his 35 vessels. Unknown to him, Dnitz had six U-boats within a days sailing of the convoy. As darkness fell that evening, U-48 was joined by U-101 (ace commander Fritz Frauenheim), U -46 (Engelbert Endrass), U-123 (ace commander Karl-Heinz Moehle), U-99 (ace commander Otto Kretschmer), U-100 (ace commander Joachim Schepke) and U-38 (ace commander Heinrich Liebe). It was one of the most formidable gatherings of U-boat commanders of the war. Not even the latest escort arrivals the sloop HMS Leith and the corvette HMS Heartsease could make the slightest difference to the gruesome onslaught that was to come.

![Freeman - Pro design patterns in Swift: [learn how to apply classic design patterns to iOS app development using Swift]](/uploads/posts/book/201359/thumbs/freeman-pro-design-patterns-in-swift-learn-how.jpg)