Contents

Jonathan Dimbleby

THE BATTLE OF THE ATLANTIC

How the Allies Won the War

VIKING

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Viking is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

First published 2015

Copyright Jonathan Dimbleby, 2015

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Cover photograph Mary Evans / The Everett Collection

Extracts from the writings of Winston Churchill are reproduced with permission of Curtis Brown, London, on behalf of the Estate of Winston S. Churchill. The Estate of Winston S. Churchill. Extracts from Mass Observation are reproduced with permission of Curtis Brown Group Ltd, London, on behalf of The Trustees of the Mass Observation Archive. While every effort has been made to contact copyright holders, the publishers will be happy to correct an errors of omission or commission brought to their attention

ISBN: 978-0-241-97211-3

THE BEGINNING

Let the conversation begin...

Follow the Penguin Twitter.com@penguinukbooks

Keep up-to-date with all our stories YouTube.com/penguinbooks

Pin Penguin Books to your Pinterest

Like Penguin Books on Facebook.com/penguinbooks

Listen to Penguin at SoundCloud.com/penguin-books

Find out more about the author and

discover more stories like this at Penguin.co.uk

By the same author

Richard Dimbleby: A Biography

The Palestinians

The Prince of Wales: A Biography

The Last Governor: Chris Patten and the Handover of Hong Kong

Russia: A Journey to the Heart of a Land and Its People

Destiny in the Desert: The Road to EI Alamein

For Daisy and Gwendolen

in the hope that one day they will want to know

how Britain was saved from the Nazis

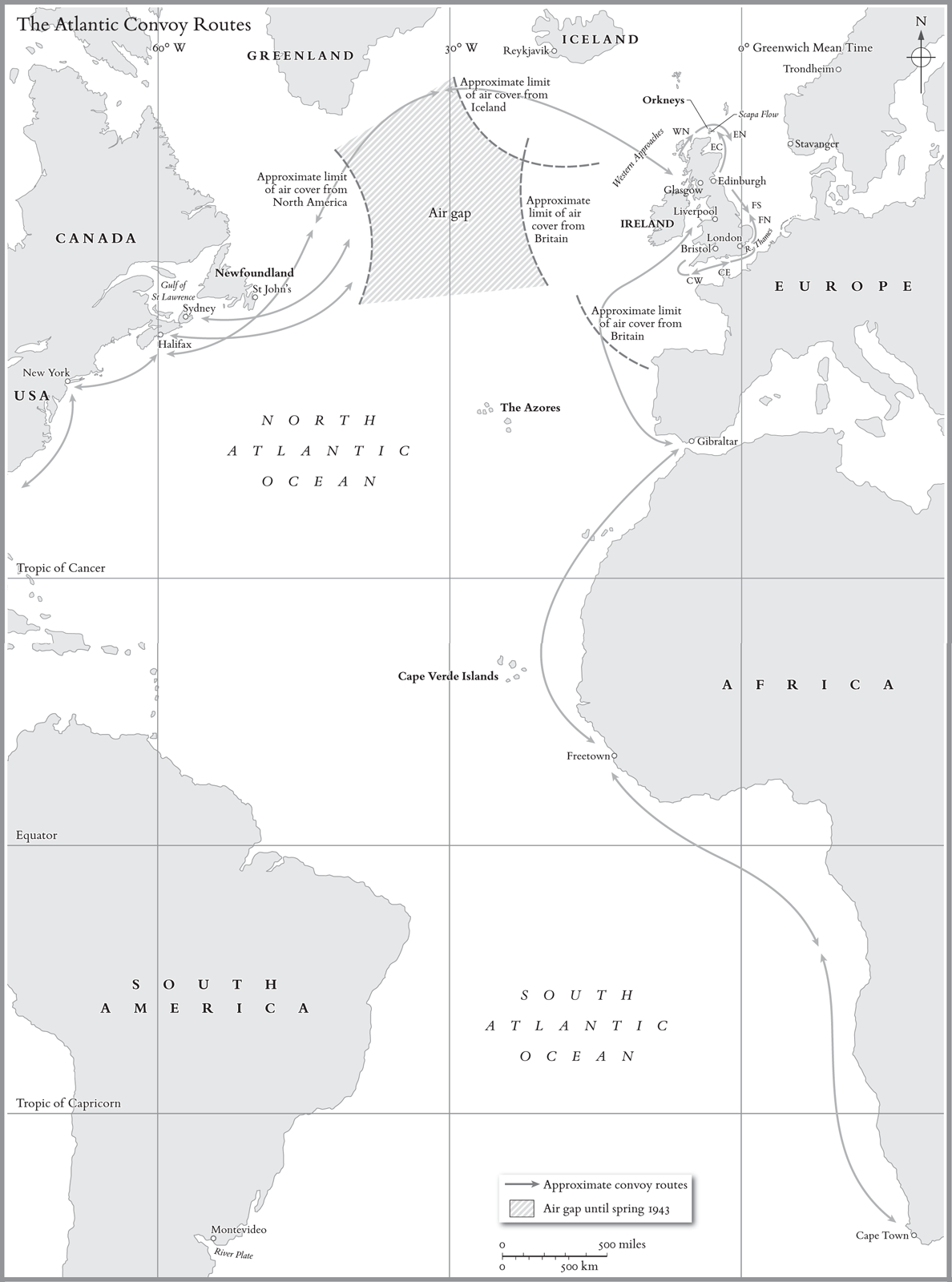

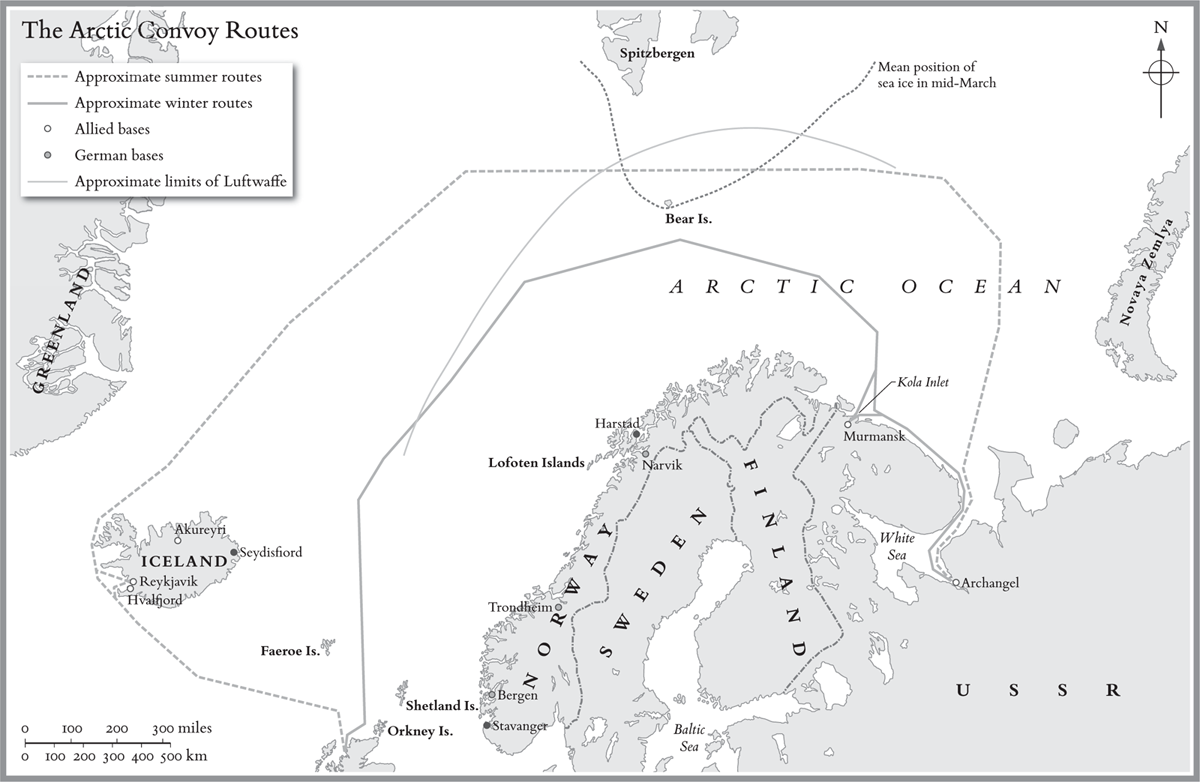

Maps and Illustrations

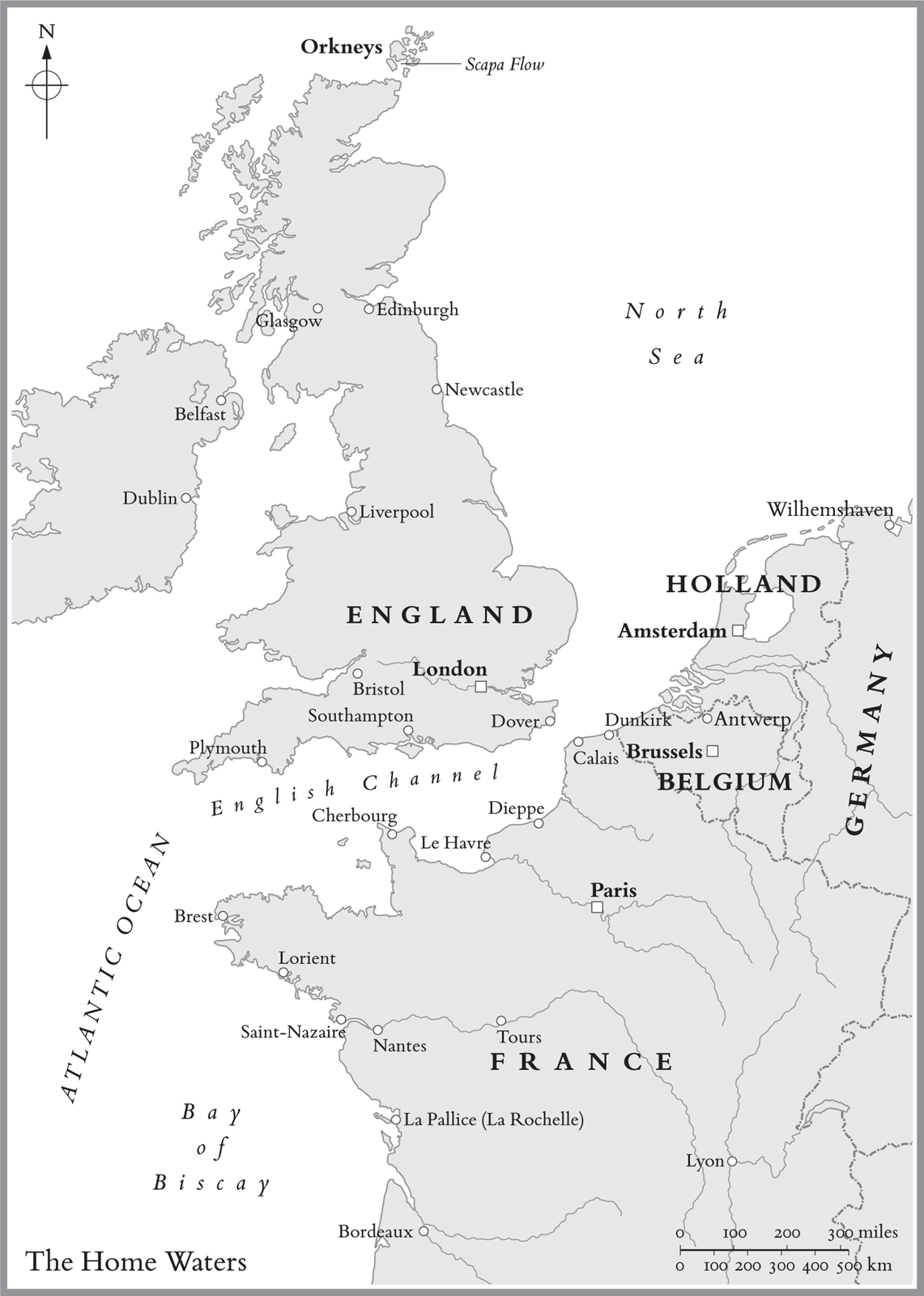

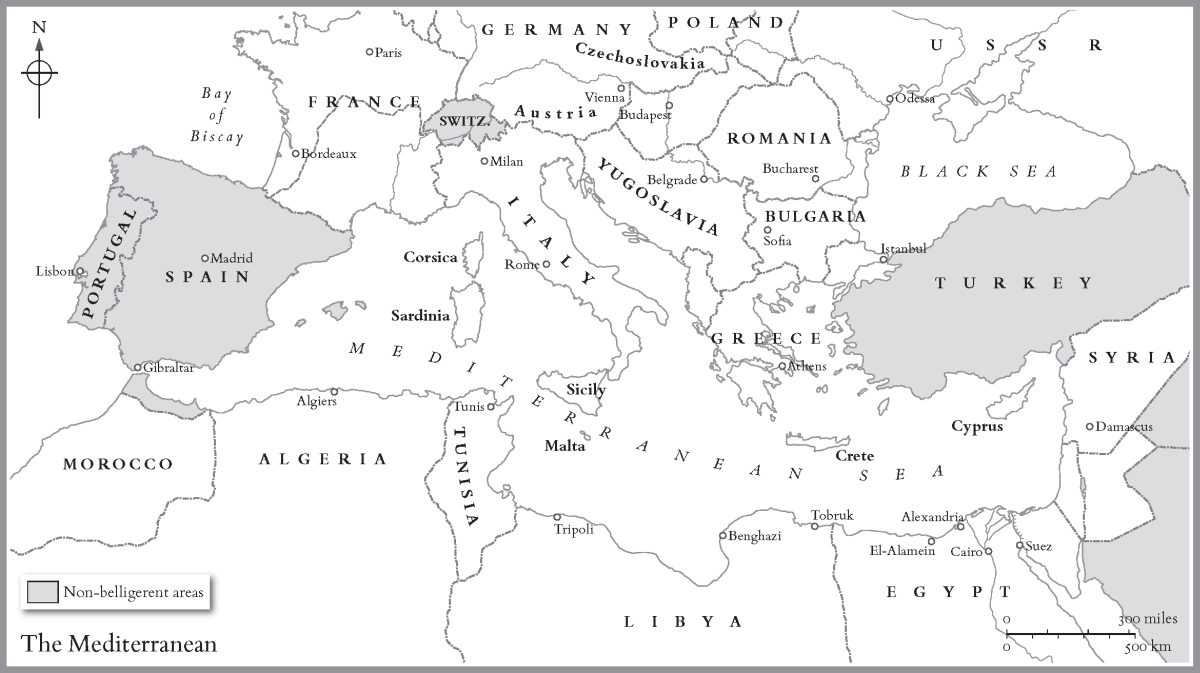

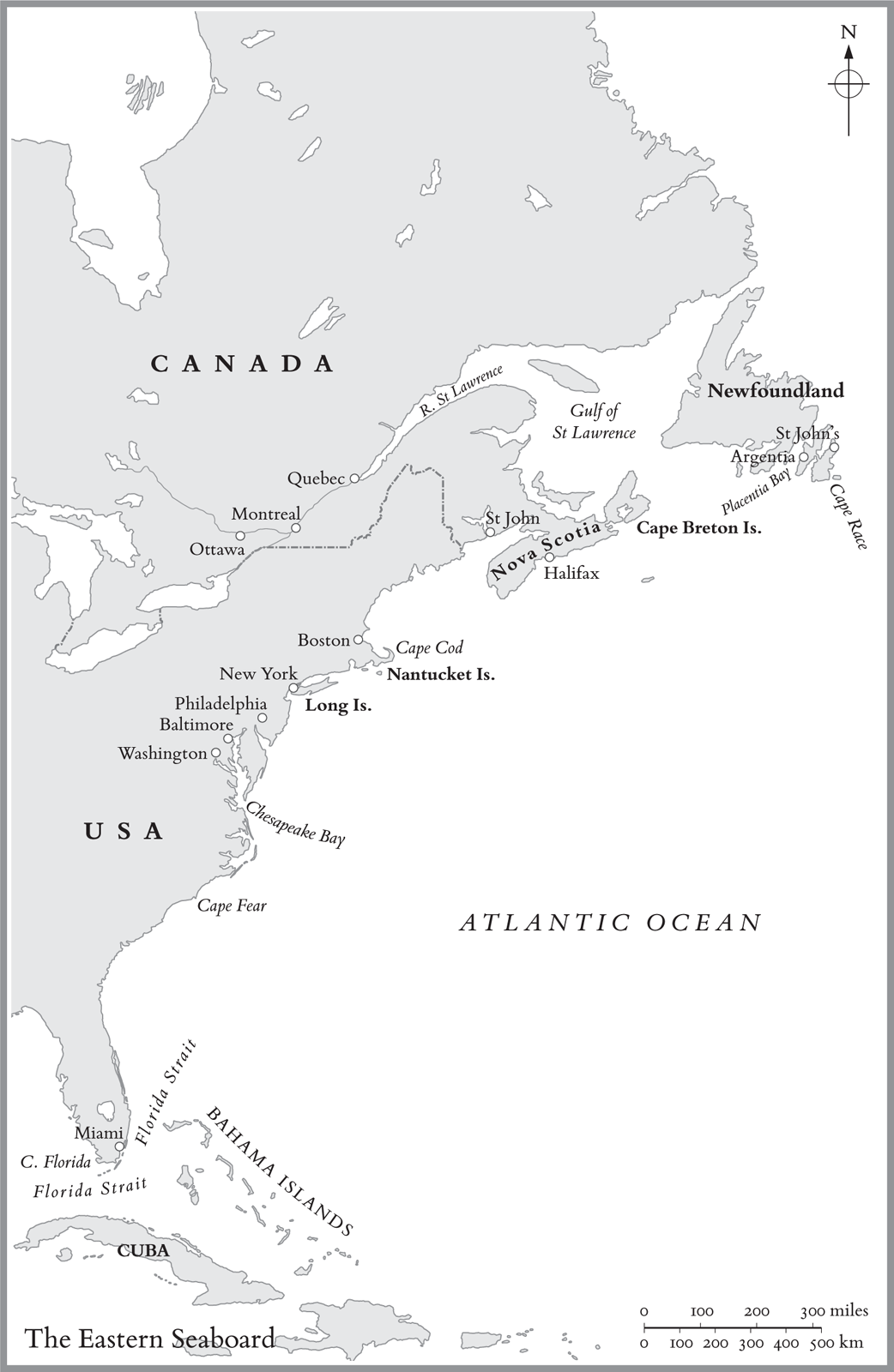

Maps

Illustrations

Preface: A Momentous Victory

On 4 May 1945, with the Third Reich crumbling about him, Hitlers successor as Fhrer, Grand Admiral Karl Dnitz, despatched a message to all U-boat commanders across the globe:

U-boat men! Undefeated and spotless you lay down your arms after a heroic battle without equal. We remember in deep respect our fallen comrades, who have sealed with death their loyalty to Fhrer and Fatherland. Comrades! Preserve your U-boat spirit, with which you have fought courageously, stubbornly and imperturbably through the years for the good of the Fatherland. Long live Germany! Your Gr. Admiral.

The longest campaign of the Second World War and the most destructive naval campaign in all history was finally over: Germany was defeated and broken. It could so easily have been otherwise.

By comparison with a global death toll of more than 60 million, the raw statistics of death and destruction in the Atlantic during the Second World War may appear modest if any death in war can be so described. Though there are no precise figures, it is widely accepted that more than 3,000 merchant ships were sunk in the Atlantic, causing the deaths of more than 30,000 seamen. On the Axis side, in a macabre equivalence, some 27,000 officers and crew or 75 per cent of those who went to war in the Kriegsmarines U-boats lost their lives; a higher death rate than that of any branch of the armed forces on any side of the conflict between 1939 and 1945.

When we think of the great struggles of those years, our minds generally turn to the Blitz, El Alamein, Anzio, Arnhem, Moscow, Leningrad, Stalingrad, Berlin, or a host of others by which our parents or grandparents may have been affected. Although territorial struggles in Europe delivered the coup de grce against the Third Reich, those battles could not have been fought, let alone won, without the Allied victory in the Atlantic. If the German U-boats had prevailed, the maritime artery between the United States and the United Kingdom would have been severed. Lacking oil for transport or heating, and without the

Even if the U-boats had failed to starve out Britain, mere survival would not have been enough to stave off disaster. Had the German Wolfsrudel (wolf packs) remained free to prowl the ocean at will, they would have prevented the Allied armies from crossing the Atlantic in sufficient numbers to join the British in the invasion of Europe: there would have been no D-Day. It is very possible that, as a result, Stalin would have elected to make a cynical accommodation with Hitler of the kind that had produced the RibbentropMolotov Pact in August 1939. In this case, the outcome of the Second World War in Europe would have been from the perspective of those who believe in freedom and democracy catastrophically different.

Anyone with a modicum of imagination knows the fear of the deep that is in all of us. Good mariners exercise constant vigilance. Distances are distorted and dangers are magnified. In the gloom of twilight, cans, tyres, beer bottles the unsinkable detritus of the sea strain the detecting eye and become imagined hazards. Conversely, a faraway light turns out to be a tanker that threatens imminent collision. A cormorants neck or the head of a curious seal are mistaken for a barely submerged rock or fatally vice versa. All but the most foolhardy know that the delights of the sea are invariably tinged with anxiety even when the waters are benign and the air is balmy. When nature delivers a hurricane that builds a gentle swell into mountainous walls of water which no human force can resist, any mariner of substance acknowledges the spasm of terror that shivers through body and spirit.

And that is in peacetime. In the Battle of the Atlantic every seaman on either side was on edge for hours and weeks at a time. The enemy was always at hand, lurking just over the horizon or prowling beneath the waves. In the air, warplanes laden with bombs emerged suddenly from the clouds to wreak havoc below. Ships and submarines may have been forbidding in appearance but their hulls were a skin of metal so thin that, as Winston Churchill once remarked of battleships in action, they were like eggshells pounding each other with hammers. Sinkings were rarely prolonged, and neither was survival in the icy waters something every sailor knew only too well.