Bibliography for Further Reading

It would be impudent (and imprudent) to attempt a thorough bibliography for a book which covers most of the course of recorded history, but some indication of sources used and places where further information can be found by anyone interested may not be out of place.

For Alexander the Great the sources are very good, considering the lapse of time and the disappearance of the works of so many ancient authors. Arrian is the chief one, and though he wrote some time after the events he chronicles, he had the great advantage of having before him the memoirs of two of Alexanders generals, Ptolemy and Aristobulus. Plutarch, Diodorus Siculus, Curtius, and Justin have also given connected accounts of Alexander, and though they often used inferior source material, they just as often check on each other, so that it is fairly easy to get at what went on.

As to Pyrrhus, the sources are just as bad as they are good for Alexander. The books of Livy that cover the period are among the lost; Diodorus does not supply much, and Polybius hardly anything. Dionysius of Halicarnassus and Hieronymus give accounts, but only in flashes; the main reliance among the ancients is Plutarch. Colonel T. A. Dodge (Hannibal) went over the battlefields and worked out the course of events with a keen military eye.

G. P. Bakers Justinian is a tower of light for anyone dealing with the period. Of course, he based on some secondary sources, such as Gibbon and J. H. Burys History of the Later Roman Empire, which have also been used here. The basic oiriginal sources are Marcellinus and Procopius. Delbrck (Geschichte der Kriegskunst) is too much of a debunker by half, but useful on details of arms and equipment.

Most of the ultimate sources for Kadisiyah are Moslem chronicles and, besides being romantic and highly mendacious, they have little regard for either figures or dates. The best is that of A1 Tabari, written in the ninth century, and translated in the Journal of the American Oriental Society. Modern writers have done a good deal of emendation and deduction; those in the Cambridge Medieval History are worth reading, and also Huarts Ancient Persia and Iranian Civilization and Sir Percy Sykes History of Persia.

The excellent papers in the Cambridge Medieval Historyare most of the background for Las Navas de Tolosa. The Spanish chronicles are windy and picturesque, without throwing a great deal of light, but they have been winnowed by several English authors, notably George Power (History of the Enpire of the Mussulmans in Spain and Portugal), H. E. Watts (The Christian Recovery of Spain), and Stanley Lane-Poole (The Moors in Spain).

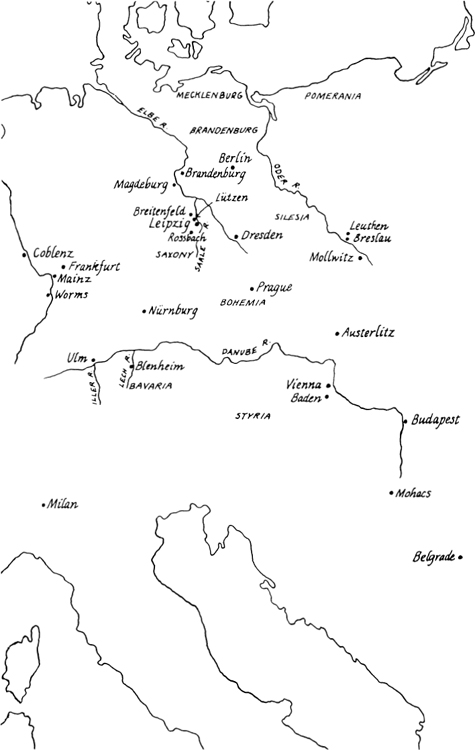

An excellent book, The Sieges of Vienna, was translated from the German of Karl Schwimmer and other sources by the Earl of Ellesmere. R. B. Merrimans Suleiman the Magnificent is worth a look, as is Eversleys Turkish Empire. An article on Salm by Johann Newald appeared in the Verein fr Geschichte der Stadt Wien, Berichte.

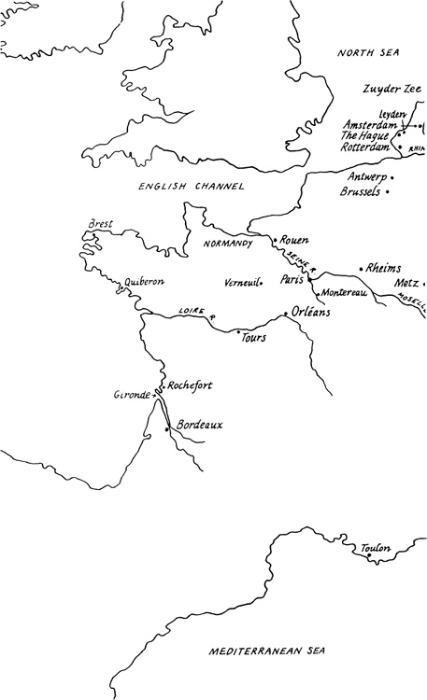

As for Leyden, J. L. Motleys Rise of the Dutch Republic still stands up after nearly a century, and he went so thoroughly into the original sources that no one need do so again. Also see Frederick Harissons William the Silent and Avermaetes Les Gueux de Mer.

Gustavus Adolphus, by Colonel T. A. Dodge, is a first-class military work. Behind it stand a number of other sources, one of the better being C. V. Wedgwoods Thirty Years War, a book of the same title by Anton Gindely, and Bryce, The Holy Roman Empire. The quotations are from George Fleetwoods Letter to His Father, which was not dug up and published in the Camden Miscellany until 1847.

For Frederick the Great nobody is quite up to Carlyle, even at this date. His research was enormous and painstaking, and he is surprisingly good on military detail. Dorns Competition for Empire is also good. Most readers will not want to bother with the numerous German sources.

Parkmans Montcalm and Wolfe is, of course, the classic for Quebec. The general background is nicely covered by Dorns Competition for Empire, naval and strategic matters by Mahans Influence of Seapower upon History, and Types of Naval Officers, while there is excellent detail on both Quebec and Quiberon Bay in the monumental History of the Royal Navy, edited by W. Laird Clowes.

On the American Revolution the best authorities are F. V. Greenes American Revolution and Douglas Southall Freemans huge George Washington. Naval matters are covered by Mahan and Clowes, mentioned above, and the Histoire de la Marine Franaise of Ren Jouan.

The literature of the Napoleonic period is so huge that even compiling a supplementary reading list from it is a formidable task. The present author has covered the military and naval background in two books; Empire and the Sea and Empire and the Glory.

The literature of the American Civil War is almost as extensive as that devoted to Napoleon. But Grants Personal Memoirs may be mentioned, also a recent volume by E. S. Miers, Web of Victory. More nearly contemporary are F. V. Greenes The Mississippi, and Battles and Leaders of the Civil War.

Further reading on Midway can be done in S. E. Morisons Coral Sea, Midway and Submarine Actions, a part of his history of the naval war; also Fuchida and Okumiya, Midway: the Battle that Doomed Japan, and the interrogations of Japanese naval officers, an official publication.

1. Arbela and the Man Who Would Be God

I

The Greeks had to go imperial to make it stand up.

This was something that Demosthenes, like many liberals insulated within the circle of his own rightness, failed to understand. He was a genius and he spoke in the name of an admirable ideal; the ideal of democracy, that the state is the collective will of all its individual components, achieving the united decision through free discussion. What he failed to see was that even in Athens this remained an unattained ideal, a precarious balance subject to destructive forces both from above and below, from within and without.

The achievement of Athens in the arts, philosophy, every intellectual pursuit, was magnificent and the democratic ideal was always present, but she was no more of a real democracy than Renaissance Florence, where there was also intellectual achievement. Democracy was in the hands of a small body of citizen voters, an island in the vast sea of slaves, metics, and unnaturalizable residents of exterior origin. There was a fatal inconsistency in Demosthenes doctrine; his banner might more accurately have read, Democracyfor Athenians only. Athens differed from Sparta, frankly an oligarchy, only in cultivating things of the spirit and in placing fewer restrictions on the personal habits of the individual. To be sure, this subtended enormous cultural differences, but they were not political differences, and the important decisions were made in the political field.

By its self-imposed limitations the Athenian democracy was incapable of real co-operation with any other state. It could form alliances, but only on a strictly temporary basis and in the face of imminent danger. It could take a place in no organization larger than itself, for this would involve the recognition of exteriors as equals, and the whole theory of Athenian democracy was that no one else had reached or could reach its own level. When Athens formed a league, it was the League of Delos, and its members were subjects. They were admitted to the sacred company of Greeks, the only civilized people in the world, but as second-class Greeks, like the lumpish Boeotians or the soft Corinthians.

Next page