Table of Contents

Central Louisiana surveyed in 1861 showing Isle Derniere relative to other major locales of Island in a Storm

Western half of Isle Derniere, from an 1853 survey showing Village Harbor, Muggahs Hotel, and the Village of Isle Derniere

Dedicated to Dee,

for giving me great joy and

standing with me through great tragedy,

&

to the late Dr. Shea Penland

of the University of New Orleans,

for first showing me the

Isle Dernieres

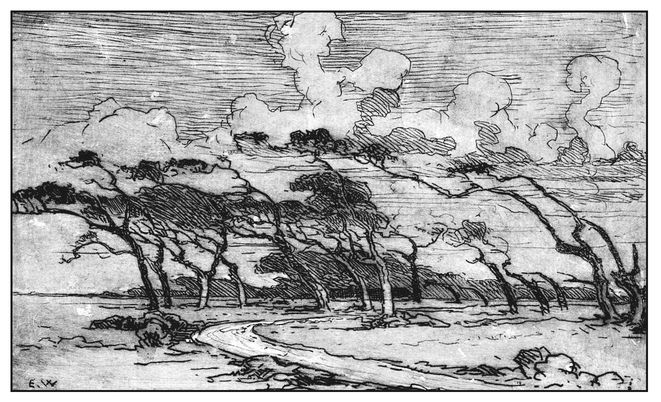

Windswept trees on a Louisiana barrier island, circa 1900

{ PROLOGUE }

An Island Changed Forever

On the Gulf side of these islands you may observe

that the treeswhere there are any treesall bend

away from the sea; and, even of bright, hot days when

the wind sleeps, there is something grotesquely

pathetic in their look of agonized terror. A group of

oaks... I remember as especially suggestive: five

stooping silhouettes in line against the horizon, like

fleeing women with streaming garments and

wind-blown hair,bowing grievously and

thrusting out arms desperately northward as to save

themselves from falling. And they are being pursued

indeed;for the sea is devouring the land.

LAFCADIO HEARN, CHITA: A MEMORY OF LAST ISLAND (1889)

In the summer of 1856, Emma Mille traveled with several of her family members to Isle Derniere, or Last Island, the westernmost of the long, sandy barrier islands that line the Gulf of Mexico shore off central Louisiana. They crossed the inhospitable Mississippi River delta to reach Isle Derniere, where they planned to spend most of the summer. They would join a former governor of Louisiana and the states speaker of the House of Representatives as well as hundreds of affluent planters, merchants, their wives and children on the narrow strip of sand that was emerging as a much-sought-after resort.

The Mille family departed from their sugar plantation near the Mississippi River town of Plaquemine (pronounced plak-a-men), located upriver from New Orleans and ten miles below Baton Rouge. Emma chatted with her family members in French. She was eighteen years old and excited about the trip. Her father had owned a house on Isle Derniere for several years, but the family had never used it until now. They likely rode in horse-drawn carriages several miles to the landing on Plaquemines riverfront. There they boarded the steamboat Blue Hammock, which made the scheduled runs from Plaquemine to Isle Derniere, a straight-line distance of ninety miles. It was owned and often captained by Michael Schlatre Jr. (pronounced Slaughter), a relative and neighbor of the Milles.

The vessels crew stoked the boiler fire, bringing a full head of steam. The two-story-high paddle wheel began to rotate, and the steamer slipped into the rivers powerful current. The seventy-four-ton side-wheeler with twin smokestacks was one of hundreds of steamboats that plied antebellum Louisianas waterways, the byways and highways of that time and place. During its journey to Isle Derniere, the steamboat would cross a remarkable sequence of diverse natural environments. It also would pass signs that foretold a coming disaster, though its passengers would not have recognized them.

Leaving the broad Mississippi River, the Blue Hammock threaded the deltas narrow bayous toward the Gulf of Mexico. These waterways cut into an easily eroded land composed of tiny bits of earth. Over thousands of years, the Mississippi had dumped these sediments into fan-shaped accumulations projecting tens of miles into the sea. It is a place that seems often unable to make up its mind whether it will be earth or water, and so it compromises, wrote Harnett Kane in Bayous of Louisiana. The result is that much of Louisiana belongs to neither element. The line of demarcation is vague and changing. The distinction between degrees of well soaked ground is academic except to one who steps upon what looks like soil but finds that it is something else. To Emma, this something else became increasingly apparent as she approached the Gulf of Mexico.

The steamer meandered through bayous shaded by two-hundred-year-old live oaks. They were squat trees with muscular, twisted limbs that dripped the silvery-gray hair of Spanish moss. In places their branches reached across the waterway in a canopy that brushed against the vessel. The steamers dual stacks billowed black smoke through green foliage.

Soon the scene changed. The bayou swelled over its channel into the surrounding trees, submerging their roots in a swamp where oak gave way to cypress. Their flagpole-thin trunks rose from still water to heights of seventy to eighty feet. At the tops of these trees, branches and leaves were so close together, and the moss so thick, that they nearly blocked the light from reaching the ground. The weird and funereal aspect of the place [was] perfect, observed Harpers Weekly of a Louisiana swamp in 1866, presenting a forbidding appearance sufficient to appall a stranger.

The steamer followed the narrow channel through the forest. The air was stagnant, the confines ovenlike. Emma and the other women aboard sweltered in their floor-length hoop dresses and layers of petticoats. Their bodices had long sleeves to shield their arms from the sun. The only relief from the heat was found on the open deck. As the vessel cut through the muggy air, it created the semblance of a breeze against their faces.

From the deck, the passengers had a clear view of the environment around them. Stumplike roots, or cypress knees, rose out of the water to help the soaring trees breathe. Among them were alligators, only their eye sockets and snouts poking above the murk, and water moccasins, skimming wavy trails in green slime. Colorful birds darted under the mossy canopy; long-legged heron and crane stood in shallow water watching for prey.

Miles across the swamp, the forest began to diminish, trees began to die, as if the water engulfing their roots had been poisoned. The sun now blazed through thinning woods, and the passengers retreated to the shade under a cabins overhang. Forest gave way to grass, willowy stems of Spartina, three to five feet high, massed into an endless prairie that was inundated by every high tide. The passengers rejoiced as they left the suffocating swamp and breathed in the fresh salt air that signaled the proximity of the sea.

The waterway splayed across the prairie, branching into an indecipherable maze of channels like veins on the back of an aged hand. The helmsman knew the correct route by pillars of grayed driftwood that had been driven vertically into the mud, marking the proper forks to follow to the sea. As the