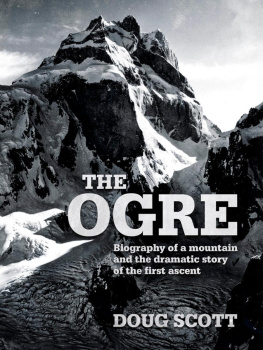

This book is a biography of the Ogre in two parts: the first part is concerned with the geological evolution and exploration from ancient times; the second part is more personal, covering the first ascent of the mountain and the drama of the descent with my two broken legs and Chris Boningtons smashed ribs.

The first section of the book involved a good deal of research that I found immensely interesting: I had been to many of the places the European explorers first saw, during eight visits to the Karakoram, the Central Hindu Kush of Afghanistan and Pik Lenin in the Pamirs. Without doubt most of what I have written has been said before, but not many can write it down so well and convincingly as Conway and Shipton, and, more recently, William Dalrymple and Rory Stewart.

This is to be the first of a series of books of a similar format. Over the next few years I intend to produce books about Kangchenjunga, Makalu, K2, Nanga Parbat, Everest and Baffin Island. The books will cover the exploration that first brought men to the mountains right up to the summit. To that extent these volumes will be innovative in that most books on mountain travel and exploration go no further than traversing the adjacent glaciers and crossing nearby cols. The climbing is from a different era before satellite phones, the avail ability of accurate weather forecasts on a daily basis and before super-lightweight equipment and plastic boots filled with closed-cell foam.

This series will cover a golden age of British Himalayan climbing between 1970 and 1985. These were brilliant days when I, for one, could have gone from one expedition to the next without a break, pushing the limits of climbing rock at great altitude and to climb the highest mountains without bottled oxygen and some without fixed ropes in complete alpine style.

In the last year new material has become available to me I came across a bundle of letters I had written to my wife and family during the expedition to the Ogre that I had not read since first writing them. Nick Estcourts diary has become available since it is now lodged with the Mountain Heritage Trust; Clive Rowland has made available his draft memoirs; and the 8mm film, together with supporting cassette tapes, have just been found by Jackie Anthoine forty years after Mo put them together.

I hope the reader will have a better understanding of those times and the part played in the climbs by my companions and the local villagers who helped us first reach the mountain and, in the case of the Ogre expedition, carried me down from it on a stretcher back to their village.

Each of the mountains I have climbed has been unique, presenting my friends and me with a new set of challenges every time. During the course of an expedition, and in overcoming these challenges, we became far more aware of ourselves and of each other. We were, for a time at least, able to return home wiser men, usually more at peace with ourselves and with more enthusiasm to do all that had to be done back home.

The one man that stands out when thinking back to the British Ogre expedition to the Karakoram mountains in 1977 is the Balti porter, Taki, who, after carrying a twenty-five-kilogram box throughout a four-day approach march, over loose moraine and slippery glacier ice, produced from the folds of his shirts and smocks on arrival at Base Camp thirty-one eggs none of which were even cracked. It is hard to know how he managed that but he did for only thirty rupees a day (1.75).

There is no way any of our expedition could have walked over that shifting chaos of moraine rock, stumbled across bare ice and waded through soft snow without breaking such a cargo. Eight weeks later eight more Balti came up the Biafo Glacier to Base Camp and, with as much consideration as Taki had for his eggs, carried me down that same rough terrain with hardly a jolt to my broken legs.

Forty years later it suddenly seems appropriate to record the significant events that brought the Ogre into being, into human comprehension, right up to the summit, and how the descent was achieved with two smashed ribs and two broken legs.

Doug Scott

September 2017

The mighty Karakoram has within the range some of the highest mountains on the planet making it the most formidable of the mountain barriers dividing the Indian subcontinent from Central Asia. The rivers draining the southern flanks of the Karakoram flow into the Indus whereas those to the north are channelled into the Yarkand to eventually disappear into the parched deserts of Xinjiang. Aeons ago this part of the earths surface was covered by an arm of the great Mesozoic Tethys Ocean that lay between the two contiguous continents of Gondwana and Laurasia containing all the land surface of the world. These two land masses split up, eventually forming the seven continents that exist today. I know this from reading Arthur Holmes Principles of Physical Geology (1944) when at school and later a revised edition (1965) when teaching geography. More recently, Colliding Continents (2013) written by a good friend and Professor of Earth Sciences at Oxford, Mike Searle, has brought me up to date.

These prehistoric continents drifted about like surface clinker on the molten core of the earth, propelled by the convection currents rising up to the earths mantle. Where two of these thermal currents came up together through the outer core and mantle to the surface and then diverged in opposite directions low mountains formed and tectonic plates were set in motion. Such activity still takes place on the ocean floor, as along the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, evidence of which is seen in Iceland. It is an island famous for its hot pools, geysers and dramatic volcanic activity sending huge plumes of ash into the atmosphere. It is also an island of increasing landmass as a result of the divergent, widening boundary between the North American tectonic plate and the Eurasian tectonic plate.

Movement of the continents resulted in an equal and opposite reaction where they collided, producing spectacular results. There the crust buckled and broke and was thrust up into huge mountain ranges. The drama is still in process in many parts of the world and none more so than in High Asia. Here the Indian plate, at the point of contact, was thrust beneath the Eurasian plate lifting Tibet to its current status the highest plateau in the world. Further west, the result of one earth-shattering thrust after another was to produce corrugations in the form of a whole series of individual mountain ranges.

The modern-day rugby scrum provides a graphic analogy for colliding continents where one front row of muscular giants dips under the other to have to reform and push again, only next time both teams are so evenly matched the front rows rise up together. As the flow of the game is brought to a halt yet again, both teams push against each other, only now to swivel round and break from each other at which point the referee blows the whistle for this infringement or fault. The first stoppage we can equate to the subduction of the Indian plate under Tibet; the second to the great continental collision along the Himalaya; and the third to the formation of huge strike-slip faults like the Karakoram fault, Kunlun or Altyn Tagh faults in Tibet, along which continental plates have moved laterally against each other.

Right in the centre of all this activity at the Roof of the World are the Pamirs, known to geographers as the Pamir Knot, from whence radiate out north-east the Tien Shan, south-east the Karakoram and Kunlun, south-west the Hindu Kush and the Pamir range itself to the west. South of the Karakoram, and running parallel to it, is the Ladakh range below which is the Indus River separating both the Karakoram and the Ladakh range from the western end of the great Himalayan range. The extent of the Himalaya is defined as lying between Nanga Parbat in the west and Namcha Barwa in the east.