The Mount Everest Foundation (MEF) was established as a Charity by the Alpine Club and the Royal Geographical Society as a result of the successful first ascent of Mount Everest in 1953 by the British and New Zealand expedition led by Brigadier (now Lord) Hunt. Under its constitution, it gives financial support to carefully selected British expeditions with both scientific and climbing objectives in the mountain regions of the world. Since it was set up the Foundation has made grants totalling over 280,000 to some 550 projects. The Foundation twice organised and ran expeditions itself the first ascent of Kangchenjunga, the third highest mountain in the world, in 1954 and the Annapurna south face expedition in 1970. In both cases the Foundation ultimately made profits, which enabled it to give more generous grants to other expeditions.

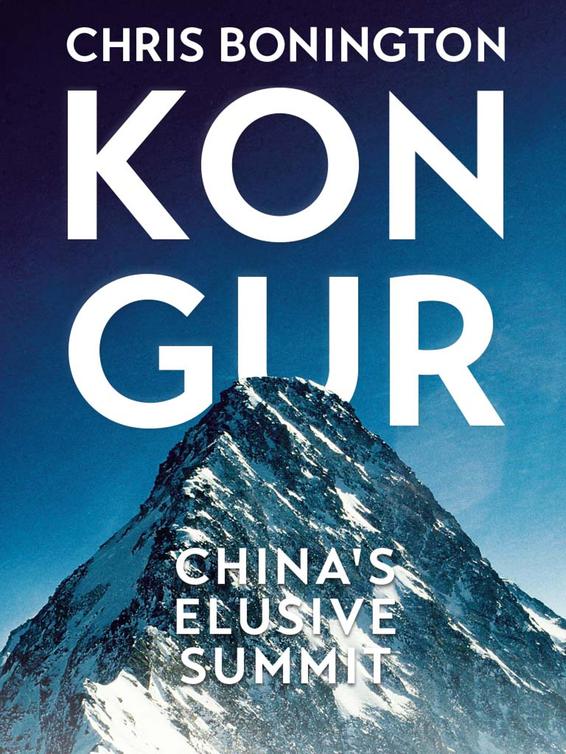

For over a decade the Foundation worked to obtain permission to mount a mixed scientific/mountaineering project in the vast area of Chinese Central Asia. Contacts were maintained with Peking and success came when Chairman Hua and his entourage visited London in 1979. The Prime Minister and Lord Carrington invited the Chairman and Vice Chairman of the MEF to meet Chairman Hua and it was agreed in principle that one of the many projects suggested by the MEF could be favourably considered. In the result, as set out in the introduction to this book, Mount Kongur was chosen. It has now been climbed and the scientific results will, when evaluated, be of great importance, not only to mountaineers, but in wider fields.

The MEF wishes to express its thanks to all who have helped during many years to achieve such a happy outcome and also to Jardine, Matheson & Co., Ltd. who not only made a massive financial contribution to the project and underwrote the costs, but who also placed at the disposal of the expedition their vast experience of the Far East and an assiduous organisational capacity that was beyond all praise.

D.L.B. April 1982

The expedition book is very similar to the expedition itself and without the help not only of my fellow expeditioners, but many others as well, I could not possibly have written this book. I should like to give my special thanks to Michael Ward, the expedition leader, for his advice, support and the many invaluable contributions he has made to the text of the book, and the team members who provided their diaries and letters home, as well as contributing to the text.

I should also like to thank Sir Douglas Busk, chairman of the Committee of Management, who provided a delightful note on the origins of the game, buzkashi. To Martin Henderson, financial director of Mathesons in London, go my grateful thanks for the notes on the fauna of the area and to Christopher Grey-Wilson of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, for identifying the flora.

My own home front has as always provided tremendous support, my wife Wendy sorting and helping select the pictures and my secretary, Louise Wilson, doing a first line edit and keying in all the corrections in the magical Wang word processor that I used for writing the book. Anders Bolinder of the Himalayan Club very kindly provided us with a wealth of detail on the climbing history and topography of the area, which was invaluable both in the main text and the .

Chris Bonington

xiii

Fragments of History

by Michael Ward

The mountains that form earths bones jut starkly out of the high deserts of Central Asia. This antique land has always stimulated the curiosity and imagination of travellers with a strong sense of history. Better known to older civilisations than our own and described for thousands of years as the Roof of the World, this is the home of gold-digging ants, of men who know the arts of levitation and self-warming without fire and of peaks on whose slopes grow herbs that cause heads to ache.

The ancient worlds of Greece, China and India joined in this vast upland waste of wind, stones and ice and the Silk Roads were the tenuous link between cultures. In 1951 when I was exploring the Nepalese side of Everest with Eric Shipton, he often talked of his years as Consul General in Kashgar. Every journey that he made on horseback outside this oasis town could bring him within minutes to the borders of the known world. This laid a train of hope that smouldered for thirty years. Expeditions are created by individuals and our venture in southern Xinjiang bore the imprint of my desires, wishes and interests. In 1972 I started my extended search for a passport to the uplands of Central Asia. Not surprisingly this failed, despite a request being taken to Peking by a mission led by Sir Alec Douglas-Home.

From occasional articles in Scientia Sinica and other sources, I knew that Chinese teams had been carrying out a series of projects in Central Asia, concerned mainly with geology and glaciology. In the course of these a number of peaks, including Everest in 1960, were climbed by them and medical research on the effects of altitude was completed. It seemed to me that a project with a similar pattern containing both scientific investigation and mountaineering would have the best chance of success. Also research and exploration have dominated my attitude and interest towards mountains. Over the next few years I wrote innumerable letters to the British Embassy in Peking and the Academia Sinica, and persuaded some of the relatively few people, politicians, scientists or businessmen, who were able to visit China to plead the cause of such a project.

In 1977 as acting chairman, and in 197880 as chairman of the Mount Everest Foundation, my main task was to bring this to fruition. My requests to the Chinese were always for areas that I thought would be politically insensitive xiv and I therefore chose regions as far away from frontiers as possible. One of the main ranges of the world and one of the least known is the Kun-lun, the Mountains of Darkness, that separate the northern edge of the Tibetan plateau from the Taklamakan desert. This range stretches from the Pamirs on the Russian border with China eastwards for a thousand miles or more. In the centre is a peak called Ulugh Mustagh (7,724 metres) which was discovered by Sven Hedin during his travels in North Tibet over eighty years ago. This was my prime target, though I mentioned a number of other areas as alternatives.