Copyright 2011 by Craig B. Smith

Text 2012 by Craig B. Smith

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

For permission to reproduce illustrations appearing in this book, please correspond directly with the owners of the works, as listed in the photography credits.

Published by Smithsonian Books

Director: Carolyn Gleason

Production Editor: Christina Wiginton

Edited by Lise Sajewski

Designed by Mary Parsons

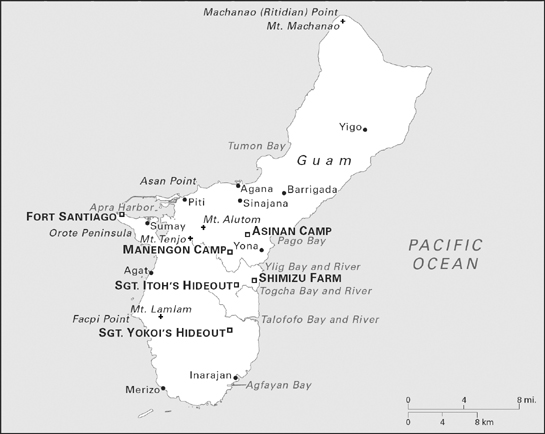

Maps by XNR Productions, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Smith, Craig B.

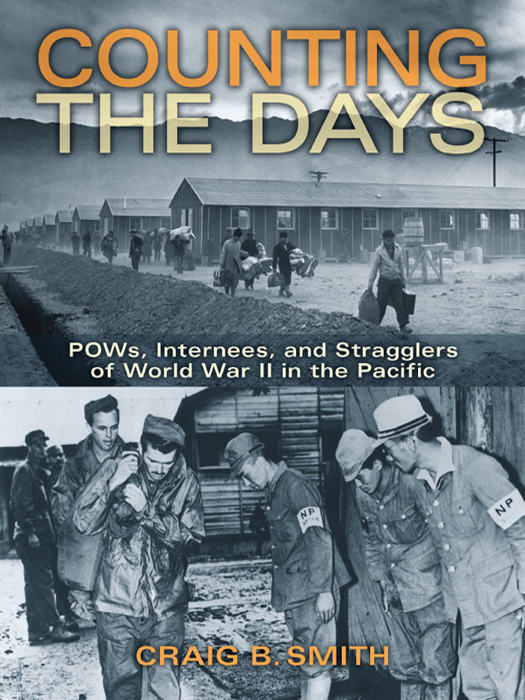

Counting the Days : POWs, Internees, and Stragglers of World War II in the Pacific / by Craig B. Smith.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

eISBN: 978-1-58834-356-7

1. World War, 19391945Prisoners and prisons, Japanese. 2. World War, 19391945Prisoners and prisons, American. 3. World War, 1939-1945Personal narratives. 4. Prisoners of warJapanBiography. 5. Prisoners of warUnited StatesBiography.

6. World War, 1939-1945Pacific Area. I. Title.

D805.A2S64 2012

940.5472091823dc23

2011047583

v3.1

Dedicated to the United States Marines who served on Guam

CONTENTS

MAPS AND PLATES

MAPS

PLATES

AUTHORS PREFACE

S eas were calm that early morning in the Gulf of Davao, at the southern end of the Philippine island of Mindanao. I was traveling by banca, a small wooden boat used by Filipino fishermen. The boatmen, a taciturn Muslim and his son, spoke little English but had been recommended to me by someone I trusted. September 1985 was not a good time to be in Mindanao. The Inter-Continental Hotel where I was staying was not a good time to be in Mindanao. The Inter-Continental Hotel where I was staying was nearly empty because terrorist activity had sharply curtailed tourism. The guerrillas were aggressively killing local mayors, police officers, and school principals. Since I fit none of those categories, I felt reasonably safe. Tourists were kidnapped only for ransom.

I would have preferred to drive around the gulf, through small villages like Mabini, to the eastern side, where an old gold-mine mill was located. However, no one would drive me theretoo dangerous to enter an area controlled by guerrillas who used illicit gold to buy weaponstherefore, the boat. I reasoned that a snorkeling expedition in the gulf would provide an innocent enough cover for the trip. The snorkel, mask, and fins were props and never got wet. Once we were well out in the gulf, the older boatman looked at me as if to ask, Where to? When I pointed to the east, he let me know by signs and words that he didnt want to take his boat too far that way. I told him to go as far as he could. As we motored east for several hours, I reflected on what had brought me to the Philippines in the first place.

From work and through family, I knew several people who were prisoners of the Japanese during World War II, the conflict the Japanese called the Pacific War. The stories of these former prisoners were so amazing that I felt compelled to interview these people to document how they had survived. They were not alone; thousands of others shared their fate, not only in Asia but in Europe as well. Many POWsor horyo as the Japanese called themsimply had the bad luck to be in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Simon and Lydia Peters, for example. Civilian noncombatants during World War II, they were nonetheless rounded up by the Japanese invaders and thrown into separate prison camps in Davao. Later, they fled from the city in a banca similar to the one in which I was sitting. They made their way across the gulf to hide in the jungle for the duration of the war, and nearly died during those desperate years. The story of their remarkable struggle to survive had drawn me to Mindanao.

In the early afternoon, the banca turned back. Wed reached the point where the opposite shore stood green on the horizonpalm trees and an inviting beach, still more than a rifle shot away, were visible. But I could tell by my captains body language that he was getting nervous, so we gave it up and returned to Davao. I took some satisfaction in the fact that I had at least retraced part of the journey Simon and Lydia had made in 1942, when they escaped from the Japanese into that same distant, foreboding jungle.

On the return to Davao, there was little breeze and the sun beat down on the open boat. The trip was uneventful except when we passed by one other banca filled with rough-looking characters. They were fishing by tossing sticks of dynamite in the water, scooping up their catch of stunned fish, and fortunately, paying no attention to us. I returned to the hotel without incident.

Once Id heard the former prisoners stories, I was not content to just record them. To the extent possible, I wanted to relive them myselfto physically see and immerse myself in the settings where they experienced the struggle to stay alive. I traveled to Japan and the Philippines, went into the jungle in Guam, visited war memorials and battlegrounds. I retraced the routes taken by the prisoners, visited the old camps where possibleor the sites if the camps no longer existedand spoke with guerrillas, freedom fighters, and others who witnessed or took part in these events.

Privately, I had another reason for understanding how these prisoners had survived. As part of my job, I frequently traveled internationally. During the 1980s, kidnapping and hostage taking were often on the news. For the innocent victims, it was another case of someone simply in the wrong place at the wrong time. Some survived captivity that stretched into years; others died in captivity or were killed. These incidents worried me; I realized that I too could become a victim. Would I be a survivor?