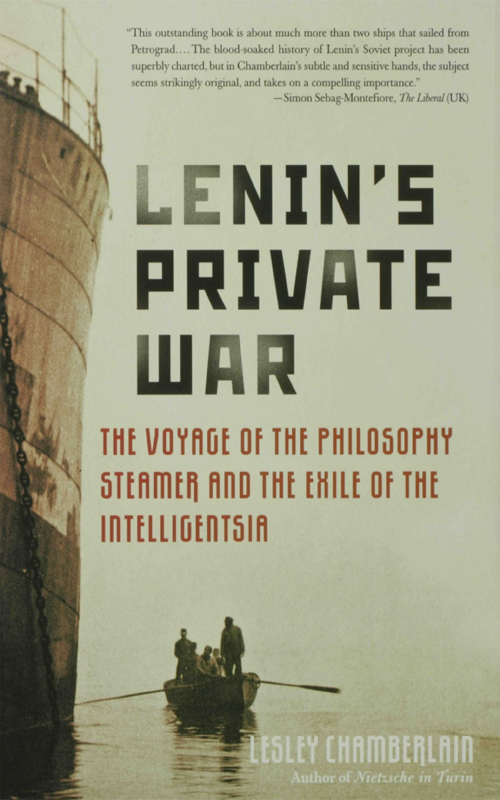

LENIN S PRIVATE WAR. Copyright 2006 by Lesley Chamberlain. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatso-ever without written permission except in die case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. For information, address St. Martins Press, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010.

www.stmartins.com

Published by arrangement with Atlantic Books, an imprint of Grove Atlantic Ltd.

Library of Congress Catalogmg-in-Publication Data

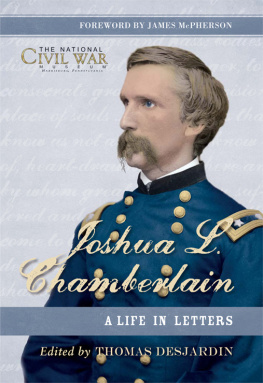

Chamberlain, Lesley.

Lenins private war : the voyage of the philosophy steamer and the exile of the intelligentsia / Lesley Chamberlain. 1st U.S. ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN-13: 978-0-312-36730

ISBN-10: 0-312-36730-9

1. IntellectualsSoviet UnionHistory. 2. Exile (Punishment)Soviet UnionHistory. 3. Soviet UnionHistoryRevolution, 1917-1921. 4. Soviet UnionSocial conditions 1917-1945. 5. Lenin, Vladimir Ilich, 1870-1924. L Philosophy steamer. II. Title.

DK265.9I55 C428 2007

325.21094709042-dc22

2007017626

ISBN-13: 978-0-312-36730-5

ISBN-10: 0-312-36730-9

First published in the United Kingdom by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Grove Atlantic Ltd.

First U.S. Edition: August 2007

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Lenins Private War

Also by Lesley Chamberlain

Motherland: A Philosophical History of Russia

Girl in a Garden: A Novel

The Secret Artist: A Close Reading of Sigmund Freud

In a Place Like That

Nietzsche in Turin

Volga Volga: A Journey Down the Great River

In the Communist Mirror

The Food and Cooking of Russia

The Food and Cooking of Eastern Europe

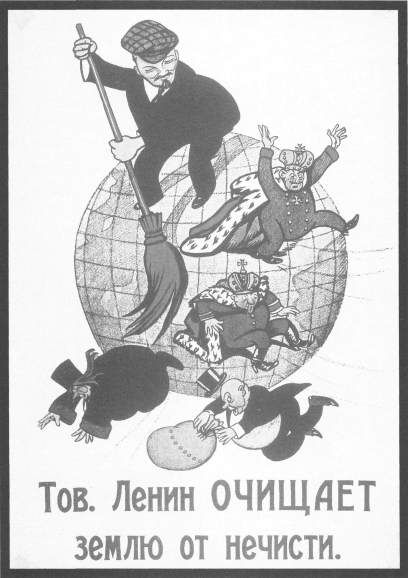

Comrade Lenin Cleans the Filth from the Land. Soviet Poster, 1920.

List of Illustrations

Frontispiece: Comrade Lenin Cleans the Filth from the Land. Soviet poster, 1920.

The author and publishers are grateful to the following for permission to reproduce images: frontispiece, 4, 6, 8, 9, David King Collection, London; 1, 14, 17, Peter Scorer; 3, 7, 10, 12, Russky Put; 5, Gorky Museum, Moscow; 13, Deutsches Schiffahrstmuseum, Bremerhafen; 15, 19, Andre Savine Collection, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; 16, John Graudenz / Ullstein Bild, Berlin.

Acknowledgements

Thanks are due to Toby Mundy and Clara Farmer at Atlantic for their support, as always, and to my husband for his encouragement and wisdom. George Leggett took a helpful interest in the quest for sources and the Society of Authors made possible a visit to Szczecin, where the archivists at Archiwum Panstwowe were most helpful. Mikhail Glavatsky sent me a copy of his important book. Peter Scorer supplied me with transcripts of his grandmothers memoirs and I also have him to thank for my introduction to Victor Frank in 1971. Katya Andreyev kindly advised me on sources for the emigration in Czechoslovakia. Rita van Duinen, of the Andr Savine Collection at the University of North Carolina, and Ivan and Misha Sovetnikov in Moscow helped bring the story alive with pictures.

A Note on Translation

All the translations from non-English material are mine unless other-wise indicated.

A Note on Transliteration

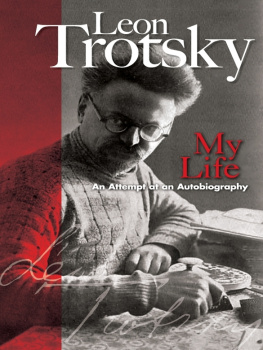

Names in the text are transliterations of the Russian originals, e.g. Lev Trotsky, not Leon. Exceptions are well-known anglicizations like Alexander (not Aleksandr). I have also preferred the ending y to T or if thus Dmitry not Dmitri, Dostoevsky not Dostoevskii. As a concession to easy reading in the text the soft-sign usually marked with an apostrophe has been omitted. References in the notes and the bibliography and Russian names quoted in non-Russian newspapers follow the style of individual publications.

Introduction

There was no violence but the attenuated police procedures eventually added almost a day to the forty-eight-hour journey the deportees faced on their specially char-tered German ship, the Qberburgermeister Haken.

A second ship, the Preussen, carrying almost as many people again mostly writers, philosophers and academics, and their dependants sailed six weeks later. Pravda, the Communist Party newspaper, recorded the expulsion of a portion of the intelligentsia but the event was hardly mentioned again in Soviet times.Bolsheviks and the founder of the Soviet Union, who masterminded the deportations and chose many of his victims by name.

When The Times reported the event from Riga, it picked out some of the most prominent victims. There was Nikolai Berdyaev, a brilliant exponent of religious philosophy, Mikhail Osorgin, a writer and journalist who made his name as a foreign correspondent in Italy, and Professor Alexander Kizevetter, a distinguished historian and founder member of the Constitutional Democratic Party, the Kadets, which opposed Lenin in 1917.

Almost nothing was said in Russia at the time. The event seemed to frighten people into silence. The writer Kornei Chukovsky, for instance, who in the Soviet Union became a famous storyteller for children, made no mention of it in his private diary, despite the pres-ence of several leading members of his Petrograd literary circle among the victims. The event was a scandal. The deportees numbered amongst the best-known and most highly qualified men in Russia. They wrote the books and newspapers that the moderate majority was still reading in 1922. They taught at the universities, institutes and schools where Bolsheviks and Kadets alike still sent their children. They excelled at the academic and journalistic professions which had recently enjoyed a renaissance, having been liberalized and profession-alized in the last decade of tsarism. Many were teachers and half a dozen were top university administrators, distinguished by their tech-nical expertise and their public service.

Philosophy Steamer suggests it was philosophers who were forced to leave, and in all eleven philosophers in the Russian style were deported. They included cultural critics and religious thinkers. Berdyaev was a mystical individualist, Frank an academic philosopher and critic, Karsavin a writer, teacher and historian of art and ideas, and Yuly Aikhenvald the translator of Schopenhauer into Russian and a popular and prolific literary critic. These thinkers clashed with Lenin and in an instant lost their homeland, because they were con-vinced that a new Russia would go astray if it did not enshrine religious moral values in its programme of social reform.

They were mostly conservative and religious in their thinking. Nevertheless, religious conservativism was not the only world outlook to be banished from Soviet Russia in the making. The young sociolo-gist Pitirim Sorokin, for whom a brilliant professional future in America lay ahead, was a spokesman for global economic freedom and Christian-humanist cultural values, while Boris Brutskus was a liberal economist. In 1922, almost before it had begun, Brutskus was already delivering public lectures on wrhy the planned economy of the Marxist-Leninists could not succeed in Russia, or indeed anywhere else. Brutskuss free-market economics so impressed an American pro-fessor of the subject seventy years later that, in 1990, as a new Russia struggled to emerge from the Soviet ashes, he sent a copy of Brutskuss 1922 article The Socialist Economy, to the cultural journal