OSPREY PUBLISHING

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

PO Box 883, Oxford, OX1 9PL, UK

1385 Broadway, 5th Floor, New York, NY 10018, USA

E-mail:

www.ospreypublishing.com

This electronic edition published in 2020 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

OSPREY is a trademark of Osprey Publishing Ltd

First published in Great Britain in 2020

Richard Endsor, 2020

Richard Endsor has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Author of this work.

All rights reserved

You may not copy, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (including without limitation electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, printing, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 978-1-4728-3838-4 (HB)

ISBN: 978-1-4728-3839-1 (eBook)

ISBN: 978-1-4728-3836-0 (ePDF)

ISBN: 978-1-4728-3837-7 (XML)

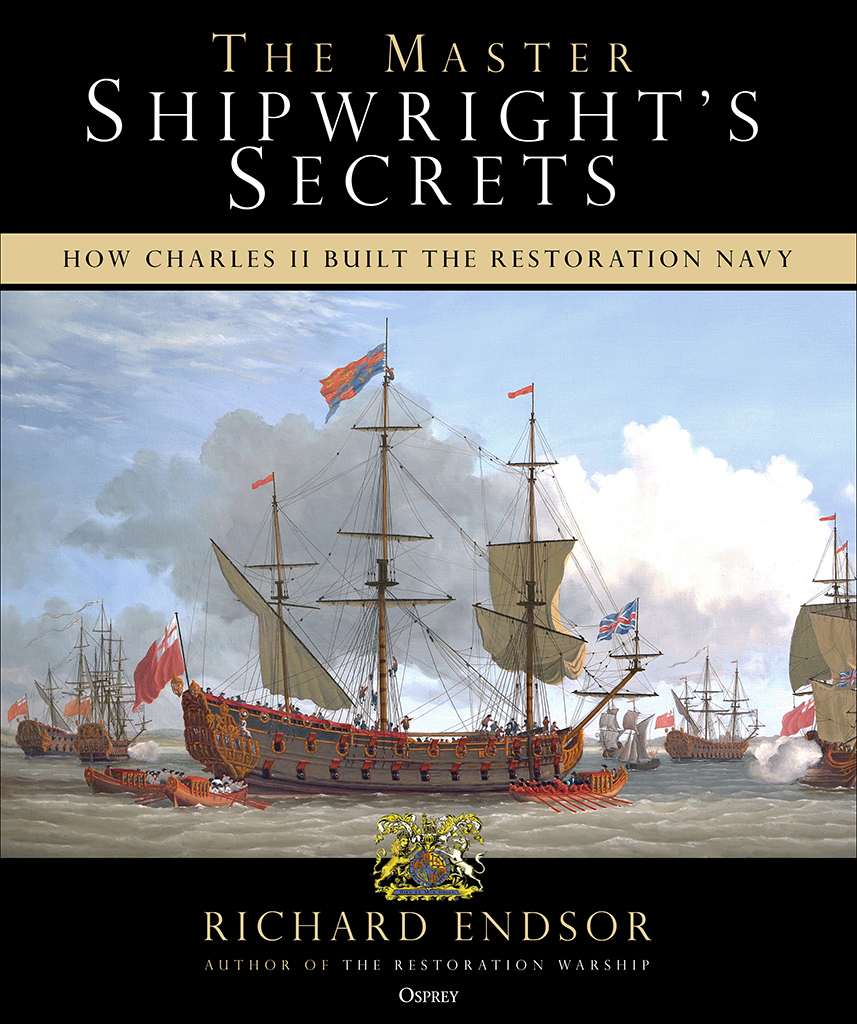

Front cover: King Charles II visiting the Tyger. Author.

Unless otherwise indicated all images form part of the authors collection. The Robinson reference numbers in the captions for the van de Velde images held in the collection of the National Maritime Museum refer to Robinson, Michael, A Catalogue of Drawings in the National Maritime Museum made by the Elder and the Younger Willem van De Velde, Volume 1, 1958 and Volume 2, 1972, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Osprey Publishing supports the Woodland Trust, the UKs leading woodland conservation charity.

To find out more about our authors and books visit www.ospreypublishing.com. Here you will find our full range of publications, as well as exclusive online content, details of forthcoming events and the option to sign up for our newsletters. You can also sign up for Osprey membership, which entitles you to a discount on purchases made through the Osprey site and access to our extensive online image archive.

CONTENTS

: Charles Berkeley

FOREWORD

It was with considerable interest that I heard a book was being written about the warship Tyger, built in 1681 for the navy of King Charles II. Charles Berkeley, the 19-year-old 2nd Baron Berkeley of Stratton, an ancestor and namesake of mine was appointed the ships first captain by the King himself.

This book has taken the author nearly ten years of painstaking research to uncover the extraordinary technical expertise used by the Kings master shipwrights. At the heart of the research is a treatise found in the Bodleian Library, Oxford that once belonged to Samuel Pepys the famous diarist who was also Secretary to the Admiralty. The treatise was written by the master shipwright who built the Tyger and describes a ship of the same type and size in considerable detail. This, together with all the other research carried out by the author, has resulted in a convincing and accurate reconstruction of the ship.

King Charles II became so closely and personally involved in building the Tyger and appointing her captain, that he boarded and dined with her officers during a short cruise. Sadly for my family, Captain Charles Berkeley died aboard the ship less than a year later and was honoured by his family by the commission of a portrait from the studio of Sir Peter Lely and two paintings of the Tyger by the famous Dutch maritime artist Willem van de Velde the Elder. Although Charles Berkeley died in the service of his country before he could fulfil his potential, other members of the Berkeley family did rise to become Admirals. Rear Admiral Sir William Berkeley was killed fighting the Dutch in 1665. Charless younger brother, John, succeeded him as the 3rd Baron Berkeley of Stratton and became a Rear Admiral: one of the ships he captained was the Charles Galley featured in this book. James Berkeley, 3rd Earl of Berkeley, was appointed captain in 1701 and enjoyed a long career in the Navy as Admiral and Commander-in-chief of the fleet. A nephew of Charles Berkeley, the Honourable William Berkeley, was first appointed captain in 1727 and by a strange chance of fate died aboard the Tyger on 25 March 1733. Some years later in 1766 George Cranfield Berkeley went to sea in 1766 at the age of just 13 and eventually rose to become a Rear Admiral. Visitors to Berkeley Castle today are reminded of this maritime connection by a number of beautiful ship models and the paintings of Charles Berkeley and his ship, the Tyger.

This maritime connection at Berkeley Castle extends to the furniture and sea chest of Sir Francis Drake. The beautiful medieval castle is one of the earliest dating from the late 12th century. Romantic as it is, King Edward II was famously murdered here in 1327 which many today believe was carried out in the most barbarous fashion. Later, during the English Civil War, an outside wall was breached and the scars remain to this day. I am grateful that modern research is still able to extend and add to our knowledge of events relating to the Berkeley family and castle, even after hundreds of years.

Charles Berkeley, November 2018

Berkeley Castle

INTRODUCTION

The Master Shipwrights Secrets in Relation to the Tyger

One of the great engineers of the Restoration age, Sir Henry Sheeres, Fellow of the Royal Society, wrote to Samuel Pepys concerning shipwrights secrets and their mysterious lines: the rising and narrowing of the breadth, floors, etc are all marked up on moulds and rods which lay up and down among the workmen and marked upon the timbers themselves which marks and measures are the results of those mysterious lines as they are called by which a ship is built.

This book is devoted to uncovering the secrets of those mysterious lines used by the master shipwrights how they were obtained, used in a draught and drawn on the floor of the mould loft. Just as elusive is the way moulds were made and used to mark out the frame timbers. These fundamental skills have almost been forgotten, and considerable research along a neglected and almost forgotten path was required in order to produce an illustrated study of their use.

The master shipwrights of King Charles II did not simply draw their curves at the traditional scale of a quarter of an inch to a foot to be later scaled up on the floor of the mould loft. Instead, actual dimensions were calculated using geometric mathematical formulae to create digitally accurate smooth curves for moulding and placing frames when building a ship. This avoided errors caused by scaling up from the draught and any distortion in the shrinking or expanding of paper.