All Under Heaven, tianxia, is the ancient Chinese idea that everything under heaven is in the charge of a single, responsible, Son of Heaven. Out of that idea came another idea: that if the single son could master the understanding of what heaven wanted, then everything under heaven would be at peace. And out of that idea came a dream: the dream of a heavenly empire on earth, modeled on nature, hierarchically ordered, and guided by principles designed to protect the common interests of a people. But what was heaven and where was it? Was it physical power or a moral force? Was heaven a single top-down mind that ordered everything across the four quarters of the earth? Or was it a reflection of the hearts and minds of the many different people, that lived within its lands?

Becoming China is the story of the tianxia dream of a heavenly order on earth, and of how that dream became the state of China today. It is also the story of what happened when the dream of the state and the dreams of its people went their different ways. Of course, it is the story of China and the Chinese. But it is also the story of some of the biggest questions known to man: what is a state, who are its people, and how do they live together? It may not be our story, but as the twenty-first century and its technologies challenge Western ideas of civilization and order, and as the same forces bring the very different people of the world together in common conversations, it is a story for us all.

If you try to possess it, you will destroy it:

If you try to hold on to it you will lose it.

(wei zhe bai zhi, zhi zhe shi zhi)

from the surviving scrolls of the Dao De Jing (500 BCE)

composed by Laozi from texts written across the

previous 1,000 years

Only if one man rules all under heaven can all

under heaven uphold that one man.

(wei yi yiren zhi tianxia, qi wei tianxia feng yiren)

Emperor Yongzheng (1722 1735)

from a text hung in the Hall of Mental

Cultivation in the Forbidden City

On 1 September 2012, the man most likely to become the next leader of China disappeared. Of course, Xi Jinping might have disappeared a day or two before, but given that his life was lived behind the screen of the Chinese Communist Party, it was only when he failed to arrive at a meeting with Hillary Clinton that he appeared to be missing to the outside world. An empty chair at a later meeting of Chinas Central Military Commission (the highest military command of the country, of which Xi was vice-chairman) seemed to confirm that he was not only missing to the outside world, but missing in China too.

With only two months before the most important Congress of the Chinese Communist Party to be convened since the time of Deng Xiaoping one at which a new leader of all would be appointed foreign journalists went on a Xi hunt. Clouds of speculation followed, while the worlds internet found itself awash with questions not only about Xi Jinpings whereabouts (rumours included Xi lying in a hospital, battling Party tigers, or throwing a temper tantrum), but whether he might never return to public view at all (stranger things have happened in China). Meanwhile across the world, deeper spirits began to ask what his disappearance meant both for the succession of power in China and for the economic and political order of everyone whose fortunes were now sailing on the Chinese ship of state. At home, the Party and its presses remained silent.

On 15 September, Xi Jinping reappeared quietly visiting a science exhibition at the China Agricultural University in Beijing. As soon-to-be leader of a Chinese Communist Party that never explained itself, no explanation was given. Far from heaving a sigh of relief, however, yet more clouds of internet speculation gathered. Was Xi Jinping fighting a bitter battle to remain the front-line candidate to lead China and the Party? Despite China having catapulted to the top of the world in terms of fortune, many even wondered whether its ancient history of dynastic rises and falls was about to repeat itself. Perhaps, just as under the last years of Maos leadership, the country was really in a secret state of collapse.

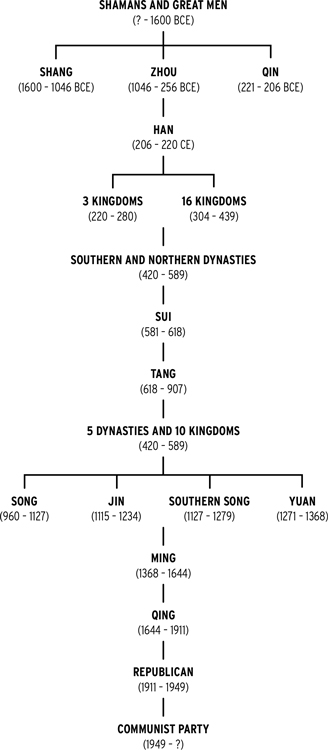

Within China, the speculation was wide and in highly political Beijing, deep. But, as usual, it was all grounded in a story that everyone knew had begun thousands of years ago, shaped by a cast of characters and questions that were echoes of battles fought many times before. The past had certainly thrown up stories far stranger than any fiction; all, however eccentric, with implications for the economics that have become the preoccupation of the present world. A world of shamans who founded a civilisation on the footprinting patterns of birds. An emperor who became so worried about the rising floods of the Yellow River that he cut off all communications between his people and heaven. Another emperor who was so concerned about the collapsing state of imperial affairs that he created a celestial Jade counterpart with a heavenly court, which every earthly minister was directed to serve as well. A foreign prince who was given the empire simply by turning up and asking for it. And a farmers son who founded a book club and went on to become master of all. They were tales that seemed to confirm what the Jade Emperor himself had once so wisely observed of the Chinese lands: Made up of the essence of both heaven and earth, nothing that goes on among these creatures in the world below should surprise us.

Perplexed, Chinese speculators scoured the past for ideas as to what might have happened. Heirs to an ancient tradition of burying secret facts in the Chinese language, they pored over every official and unofficial Party sentence for the coded messages that might give them a clue. (With thousands of Chinese characters and only a few hundred syllable-sounds to match them, there is always a wide range of written characters, which, sounding the same as a word too dangerous to write, can carry a hidden meaning). Guesses were everywhere, but no real clues were found. The character code was, however, very useful to the many who, now convinced that China was on the brink of revolutionary change, used it to bury barbs of meaning in the internet blogs with which they shared their more daring speculations. (They also used the code to make some acerbic observations about life in a land where the whereabouts of a leader is a matter for heaven alone.)

Outside China, the quality of the speculation was rather different. Whereas Chinese minds had always understood the need to think deeply, Western minds had been more concerned to find the shorter, sharper, simpler answer. The observation of a fourth-century BCE shaman-scholar that he who perceives the oneness of everything does not know about the duality of it had not been given much attention beyond Chinas Great Wall. Chinese with deep insights grounded in long study and experience were told to simplify their ideas for Western readers who could really only be expected to read a paragraph or two. Western minds themselves (many wise, but usually without the benefit of a China education or experience) made sweeping declarations on the basis of the fragments of facts, anecdotes and assumptions that had been gathered in the rush of Chinas rapid economic rise. Not surprisingly, everyone stayed confused.

Next page