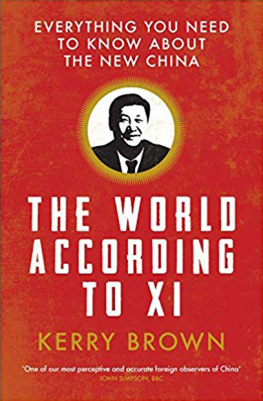

Kerry Brown is Professor of Chinese Studies and Director of the Lau China Institute at Kings College London, and Associate Fellow specializing in Asia at Chatham House. With 20 years experience of life in China, he has worked in education, business and government, including a term as First Secretary at the British Embassy in Beijing. He writes regularly for international media, and has authored over ten books on contemporary China, among them The New Emperors (I.B.Tauris, 2014), Contemporary China (2012) and Struggling Giant: China in the 21st Century (with Jonathan Fenby, 2007).

Xi is determined to reshape China and bring it into the centre of the international stage. We all feel these profound changes, but few of us have the ability to step back, put Xi in perspective, analyse his rise, and guess where Xi will take us. Kerry Brown has it, and he delivers. This book provides an excellent account of Xis rise, his visions, his determination, and the future he is making for China and for the world. All who are interested in China and its global role should read it.

Yongnian Zheng, Director of the East Asian Institute,

National University of Singapore

Kerry Brown is one of our most perceptive and accurate foreign observers of China

John Simpson, BBC

CEO, China is a thoughtful and thought-provoking study of Chinas current leader A fascinating glimpse into the workings of the Chinese leadership.

Frank Ching, First Bureau Chief in Beijing

for the Wall Street Journal and author of Ancestors

A necessary read for anyone who thinks about China, which is most of us these days Kerry Browns book is very timely, thorough and insightful, and gives some of the prevailing orthodoxies a bit of an overdue nudge. A lot of the commentary about Xi to date has been fairly trite; this book isnt.

Clinton Dines, former CEO of BHP Billiton

in China and an expert on Chinese business

One of the most useful studies available of how power works in todays China. I doubt any other writer provides as many insights into how a closed system makes decisions and allocates authority.

Bob Carr, Director of the AustraliaChina Relations

Institute at UTS, former Australian Foreign Minister

and longest-serving New South Wales Premier

Published in 2016 by

I.B.Tauris & Co. Ltd

London New York

www.ibtauris.com

Copyright 2016 Kerry Brown

The right of Kerry Brown to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by the author in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or any part thereof, may not be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

References to websites were correct at the time of writing.

ISBN: 978 1 78453 322 9

eISBN: 978 0 85772 961 3

ePDF: 978 0 85772 757

A full CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

A full CIP record is available from the Library of Congress

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: available

Typesetting and eBooks by Tetragon, London

Printed and bound in Sweden by ScandBook AB

Dedicated to Jim ODonoghue and Katherine Peters

Contents

Master Tseng said, Every day I examine myself on these three points: in acting on behalf of others, have I always been loyal to their interests? In intercourse with my friends, have I always been true to my word? Have I failed to repeat the precepts that have been handed down to me?

Analects 1.4

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Tomasz Hoskins and his colleagues at I.B.Tauris for their continuing support in commissioning this work, as well as to my former colleagues at the University of Sydney and Chatham House in London for all their insights, inspirations and assistance. I am also, as ever, grateful to my daughter Tanya Brown for her patience and forbearance while I wrote this in early 2015, and to Kalley Wu for her support. I am extremely grateful for the help of Emily Dunn, Simone van Nieuwenhuizen, Caroline Chong, Samuel Johnson and Haimin Huang for their work on correcting the text, and to Alexander Middleton for copy-editing it so well, Alex Billington at Tetragon for his work on the production, and Sarah Terry for her proofreading.

Note on the Text

All transliterations of Chinese into English are in Pinyin. The translations from Chinese to English in the text are my own, unless otherwise stated in the endnote references.

Preface

There is an occupational hazard for anyone who chooses to write about Chinese politics in the second decade of the twenty-first century. We may live in an age of openness and information, but the inner workings of the Chinese political system, and in particular the lives and thinking of its leaders, remain one of the few bastions of opacity. Those who choose to write about it, therefore, have to face two different kinds of criticism. From one side, there is the complaint often made from within China that anyone trying to work out its internal politics doesnt really understand because he or she is an outsider. These people use dark phrases like you dont really know how China works. The implication is that the system is so fiendishly complicated and successfully protective of its secrets that only those deep within can truly understand it and of course, they are the last to say what they know. There are also many outside China who have a vested interest in maintaining this image of unknowability. To them, years of observation and careful scrutiny of name lists are the only legitimate pathway to understanding. Perhaps tellingly, one of the diplomats I worked with in the past combined professional interest in elite Chinese politics with collecting dead moths. He got a lot of things right, but spoke about China and the Chinese like they were taxidermy exhibits in a museum.

On the other side, there is the complaint that those who try to write with some sympathy, or attempt to understand internal Chinese politics too much on its own terms, are apologists, people who have gone native and are guilty of producing external propaganda for an immoral system. The work of (the American) Robert Lawrence Kuhn is most representative here. His earlier biography of Jiang Zemin was one of very few based on meetings and first-hand encounters with Chinas then president, and his follow-up book on the new leadership in 2011 was similarly advantaged by excellent top-level access. Kuhns writings, however, have been criticized for being over-respectful and fawning, presenting leaders like Xi in an uncritical light. This accusation of partisanship is a common taunt against those who write about Chinese politics in a far more neutral tone than Kuhns.

After almost a quarter of a century trying to work out what power means in China, how it is exercised and what makes Chinese elite leaders tick, something I have come to realize is that hybrid approaches work best, taking methods and insights from diverse areas and trying to link them to what one observes in China. It is a good idea too to treat Chinese political behaviour the way one would address political habits and modes of action anywhere. The United Kingdom and the United States both have peculiarities about their systems and the way people operate in them. But, broadly speaking, people strive for power and are motivated to acquire that power for very similar reasons no matter where they are. We are all part of one species, so there should be no shock about this. The important thing is to keep a sense of proportion between the unique features of specific systems and their shared attributes. Overstressing one and understressing the other are both mistaken.