Contents

Pagebreaks of the print version

THE THIRD REVOLUTION

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

Elizabeth Economy 2018

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

CIP data is on file at the Library of Congress

ISBN 9780190866075

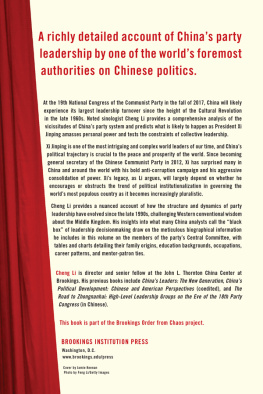

The Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) is an independent, nonpartisan membership organization, think tank, and publisher dedicated to being a resource for its members, government officials, business executives, journalists, educators and students, civic and religious leaders, and other interested citizens in order to help them better understand the world and the foreign policy choices facing the United States and other countries. Founded in 1921, CFR carries out its mission by maintaining a diverse membership, with special programs to promote interest and develop expertise in the next generation of foreign policy leaders; convening meetings at its headquarters in New York and in Washington, DC, and other cities where senior government officials, members of Congress, global leaders, and prominent thinkers come together with CFR members to discuss and debate major international issues; supporting a Studies Program that fosters independent research, enabling CFR scholars to produce articles, reports, and books, and hold roundtables that analyze foreign policy issues and make concrete policy recommendations; publishing Foreign Affairs, the preeminent journal on international affairs and U.S. foreign policy; sponsoring Independent Task Forces that produce reports with both findings and policy prescriptions on the most important foreign policy topics; and providing up-to-date information and analysis about world events and American foreign policy on its website, www.cfr.org.

The Council on Foreign Relations takes no institutional positions on policy issues and has no affiliation with the U.S. government. All views expressed in its publications and on its website are the sole responsibility of the author or authors.

For David, Alexander, Nicholas, and Eleni

CONTENTS

Map of China and Its Provinces

Credit: mapsopensource.com

Chinas rise on the global stage has been accompanied by an explosion of facts and information about the country. We can read about Chinas aging population, its stock market gyrations, and its investments in Africa. We can use websites to track the air quality in Chinese cities, to monitor Chinas actions in the South China Sea, or to check on the number of Chinese officials arrested on a particular day.

In many respects, this information does what it is supposed to do: keep us informed about one of the worlds most important powers. From the boom and bust in global commodities to the warming of the earths atmosphere, Chinese leaders political and economic choices matter not only for China but also for the rest of the world; and we can access all of this information with a few strokes on our keyboards.

Yet all these data also have the potential to overload our circuits. The information we receive is often contradictory. We read one day that the Chinese government is advancing the rule of law and hear the next that it has arrested over two hundred lawyers and activists without due process. Information is often incomplete or inaccurate. In the fall of 2015, Chinese officials acknowledged that during 20002013, they had underestimated the countrys consumption of coal by as much as 17 percent; as a result, more than a decade of reported improvements in energy efficiency and greenhouse gas emissions were called into question. We are confused by dramatic but often misleading headlines that trumpet Chinas every accomplishment. More Americans believe (incorrectly), for example, that China, not the United States, is the worlds largest economic power. It is a country that often confounds us with contradictions.

The challenge of making sense of China has been compounded in recent years by the emergence of Xi Jinping as Chinese Communist Party general secretary (2012) and president (2013). Under his leadership, significant new laws and regulations have been drafted, revised, and promulgated at an astonishing rate, in many instances challenging long-held understandings of the countrys overall political and economic trajectory. While previous Chinese leaders recognized nongovernmental organizations from abroad as an essential element of Chinas economic and social development, for example, the Xi-led government drafted and passed a law to constrain the activities of these groups, some of which Chinese officials refer to as hostile foreign forces. In addition, contradictions within and among Xis initiatives leave observers clamoring for clarity. One of the great paradoxes of China today, for example, is Xi Jinpings effort to position himself as a champion of globalization, while at the same time restricting the free flow of capital, information, and goods between China and the rest of the world. Despite his almost five years in office, questions abound as to Xis true intentions: Is he a liberal reformer masquerading as a conservative nationalist until he can more fully consolidate power? Or are his more liberal reform utterances merely a smokescreen for a radical reversal of Chinas policy of reform and opening up? How different is a Xi-led China from those that preceded it?

I undertook this study to try to answer these questions for myself and to help others make sense of the seeming inconsistencies and ambiguities in Chinese policy today. Sifting through all of the fast-changing, contradictory, and occasionally misleading information that is available on China to understand the countrys underlying trends is essential. Businesses make critical investment decisions based on assessments of Chinas economic reform initiatives. Decisions by foundations and universities over whether to put down long-term stakes in China rely on an accurate understanding of the countrys political evolution. Negotiations over global climate change hinge on a correct distillation of past, current, and future levels of Chinese coal consumption. And countries security policies must reflect a clear-eyed view of how Chinese leaders words accord with their actions in areas such as the South China Sea and North Korea.