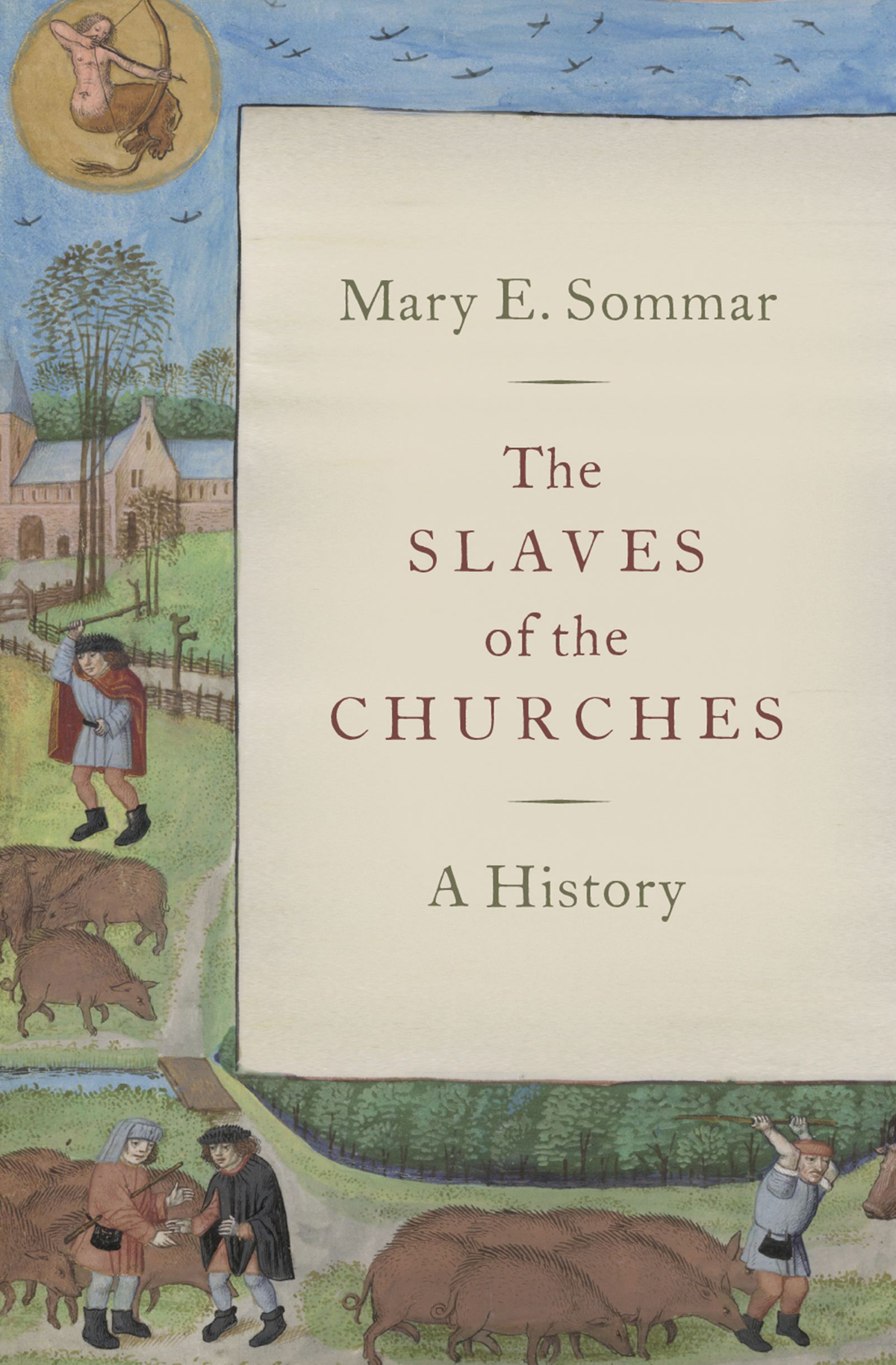

The Slaves of the Churches

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

Oxford University Press 2020

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Sommar, Mary E., 1953 author.

Title: The slaves of the churches : a history / Mary E. Sommar.

Description: New York, NY, United States of America :

Oxford University Press, 2020. |

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020007944 (print) | LCCN 2020007945 (ebook) |

ISBN 9780190073268 (hardback) | ISBN 9780190073282 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Slavery and the churchHistoryto 1500. |

SlaveryReligious aspects.

Classification: LCC HT913 .S66 2020 (print) |

LCC HT913 (ebook) | DDC 306.3/62dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020007944

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020007945

With love and gratitude to those unnamed ancestors who were among the subjects of this book.

Contents

Every work of scholarship owes a great deal to the efforts and experience of others. Some of that debt is acknowledged in the footnotes. And the rest, here. I am very thankful to many colleagues, friends, and family, especially David Collins, Gottfried and Margaret Heller, Richard Helmholz, Kathryn Kleinhans, Kathy Kremer, Tonya Johnson, Barbara Jones, Peter Landau, John McLarnon, Clarence Maxwell, Hermann Nehlsen, Kenneth Pennington, Ashley Sherman, Harald Siems, Albert Sommar, Charley Sommar, Loree Strickler, Paul Stuehrenberg, and Anders Winroth, without whose assistance and encouragement this book would never have been possible. In addition, thanks are due to the students in my Global Slavery seminar for their insightful and probing questions as well as to the library staffs of Yale University and Millersville University for their invaluable assistance. And, lastly, I owe a great debt of gratitude to the staff at the Oxford University Press, especially Cynthia Read, Hannah Campeanu, and Rick Stinson for turning my scribblings into something that can be shared with others.

One more acknowledgement must be made. An overwhelming anguish about the legacy of slavery is flooding our cities as this book goes to press. While a scholar must maintain a certain objectivity and distance from her work if an historical study is to have any significance, this does not mean that, when the work is done, she will not weep.

| ANF | Ante-Nicene Fathers (New York 1885) |

| CHC | The Cambridge History of Christianity (Cambridge 2006) |

| CWHS | The Cambridge World History of Slavery, vol. 1: The Ancient Mediterranean World, ed. K. Bradley and P. Cartledge (Cambridge 2011) |

| DDC | Dictionnaire de droit canonique |

| EOMIA | Ecclesia Occidentalis Monumenta Iuris Antiquissima, ed. C. H. Turner (London 1907) |

| HMCL | History of Medieval Canon Law, ed. W. Hartmann and K. Pennington (Washington, DC 1999) |

| MGH | Monumenta Germaniae Historica |

| MIC | Monumenta Iuris Canonici |

| NPNF | Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers (New York 18901900, 2nd series 1991) |

| PG | J.-P. Migne, Patrologia graeca |

| PL | J.-P. Migne, Patrologia latina |

| RSV | Revised Standard Version |

| ZRG.KA | Zeitschrift der Savigny-Stiftung fr Rechtsgeschichte. Kanonistische Abteilung |

And I realized the timeliness of my question about those who were known as servi ecclesiarum, the slaves of the churches.

More than fifty years ago, David Brion Davis looked at the institutional continuity between ancient and modern slavery in an effort to problematize slavery as a focus of academic inquiry. In other words, he tried to figure out a way to define just what was meant by the word slavery. There are many different ways that human beings throughout history have dominated other humans and forced them to do their bidding. But dispassionate scholarly inquiry requires a clearly defined object and clearly defined rules for investigation. This helps us to avoid the temptation to impose modern ideas of morality on our historical subjects, judging the ancients according to standards of which they could not possibly have been aware. Instead, we can analyze their behavior based on what we are able to learn of their own standards. The present work is an attempt to understand just what those standards were in connection with ecclesiastical servile dependents and to find out how these standards came to be.

The results here say nothing to challenge that. Neither does this study aim to describe in any detail how ecclesiastical institutions managed their affairs, their agricultural estates, or their domestic arrangements. These factors varied a great deal chronologically and, even more so, geographically. A comprehensive account would be unwieldy, and anything less would lead to conclusions that were valid only in connection with a particular sample population. This sort of analysis must await later investigations. The focus of the present inquiry is fairly narrow and thus able to be very clear: What were the churchs regulations concerning its own unfree dependents? The temporal boundaries extend from the very beginning of Christianity, when norms for the behavior of the fledgling church were vague and varied, to the end of the medieval period, when secular as well as ecclesiastical jurisprudence became an international theoretical discipline. Eventually church law was relegated to the domain of the theologians.

This study also makes no attempt to evaluate how well the churches in various regions and in various centuries held to their regulations. For one thing, there is simply too much data from these fourteen centuries for such a global analysis to be practicalor comprehensible. And, more importantly, the available data does not generally document how well people broke or kept the rules except when there was a large scandal. Court records, especially from the early periods, are notoriously incomplete. Any analysis would be skewed in favor of sensational cases and would mislead us about the real picture. Again, these questions must be left for later investigation. This study traces the churchs own norms concerning ecclesiastical unfree dependents and the evolution of these norms over time, with attention to how they were affected by the social, economic, political, and legal developments of the However, very little attention has been directed at the relevant ecclesiastical norms of the earlier centuries, and nothing, to my knowledge, has focused on the regulation of ecclesiastical servile dependents.